Abstract

Despite numerous empirical studies of practices in software development, little is known about cooperation between front-end developers and User Experience (UX) professionals. This paper provides insights into how front-end developers view UX professionals and what they expect from UX professionals. This is important for UX professionals who want to know their users to better cooperate with their stakeholders.

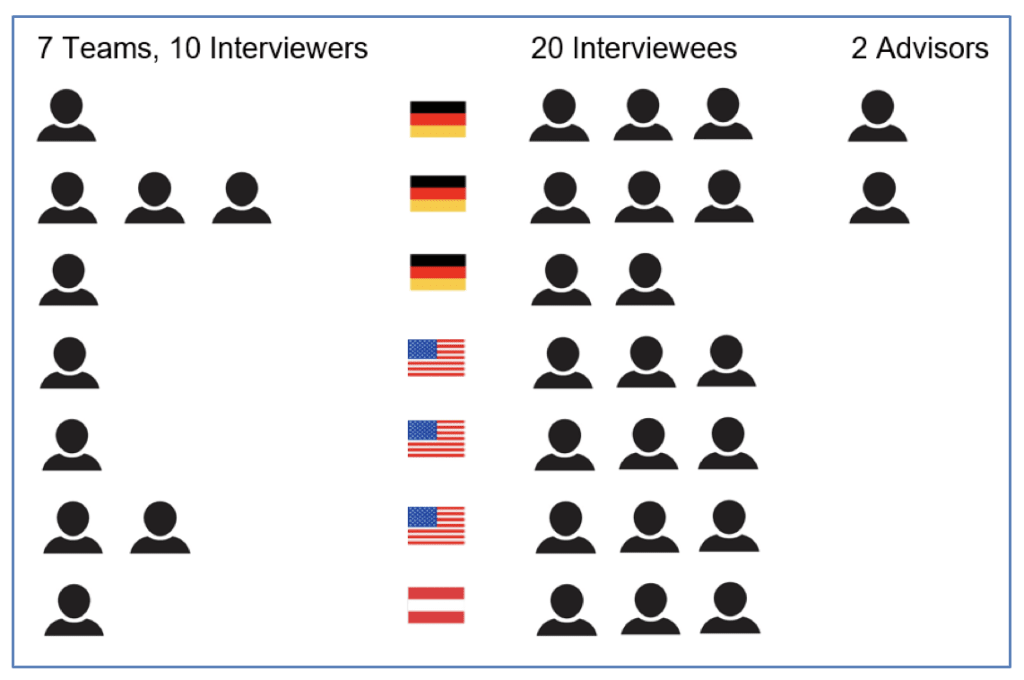

Our study revealed insights obtained from UX professionals interviewing front-end developers. Seven teams comprising 10 experienced UX professionals participated in the study. Each team independently recruited and interviewed two or three experienced front-end developers from different organizations using a semi-structured interview format. There were 20 interviews in total.

We used quotes from the front-end developers to derive four front-end developer personas that exemplify typical attitudes towards UX and UX research. Step-by-step descriptions of the development process, a Developer Journey Map, were extracted from the 20 interviews. There were striking similarities between the Developer Journey Maps. We created a general Developer Journey Map, focusing on touchpoints between front-end developers and UX professionals.

Our key advice for UX professionals who want to improve cooperation with front-end developers includes the following: respect front-end developers as partners and engineers, rather than subordinates; support the front-end developer flow state by specifying, and helping them with, edge cases; and be available during implementation to answer questions quickly, and in order, to avoid interrupting their flow.

Keywords

developers, attitudes, UX, cooperation, Developer Journey Map, front-end developer, personas, edge cases

Introduction

Communication and collaboration between front-end developers and UX professionals in software development are crucial to achieve truly usable software, such as apps and websites.

Although there are many articles about the processes developers follow and how to create the best environment for optimizing the development process, we found few articles about the cooperation between front-end developers and UX professionals.

As to developers, Curtis et al. (1988) studied the problems of designing large software systems through interviewing personnel from 17 large projects. Although a bit dated, the article’s descriptions of the basic mechanisms of software development (organizations, people, and power) are probably not that different today.

Curtis et al. (1988) found that these were the most salient problems:

- The thin spread of application domain knowledge

- Fluctuating and conflicting requirements

- Communication and coordination breakdowns

Curtis et al.’s analysis of communication and coordination breakdowns served as a guide for our current study. To prevent such breakdowns, they recommended improved communication, which can be achieved, for example, through reviews: “Communication was often cited as a greater benefit of formal reviews than was their official purpose of finding defects.” They also recommended a company culture that fosters “boundary spanners” who have good communication skills and a willingness to engage in constant face-to-face interaction. For example, boundary spanners translate customer needs into user stories understood by software developers, and they keep communication channels open between rival groups.

In a recent study of the causes of friction in the developer experience, Forsgren et al. (2024) reportedthat important elements of developer experience are these:

- Flow state: Developers who have a significant amount of time carved out for deep work feel 50 percent more productive compared with those lacking such dedicated time.

- Feedback loops: Developers who report fast code-review turnaround times feel 20 percent more innovative compared with developers who report slow turnaround times. Teams that provide fast responses to developers’ questions also report 50 percent less technical debt than teams whose responses are slow. (Technical debt is the additional cost that results from releasing easier technical solutions instead of releasing the best approach.)

Our main takeaway from Forsgren et al. was that supporting developers’ flow state (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996) and tight feedback loops were important points of interest for our study.

Our goal was to identify facilitators and barriers in the cooperation between front-end developers and UX professionals in order to improve communication between these two important stakeholders during the development process. Accordingly, in this paper we present the essence of the information provided by front-end developers in 20 interviews conducted by professional interviewers.

Roles Discussed in This Paper

In this paper, we focused on the following roles:

UXP UX professional is an umbrella term for UX designer (UXD) and UX researcher (UXR).

UXD A UX designer develops efficient and appealing experiences for end users, frequently using data from workflow analysis and user research. UXDs must have excellent technical and problem-solving abilities and creativity (Hapy Design, 2024).

UXR A UX researcher observes and interviews real users and other stakeholders to understand and specify the product’s context of use. The results are used to specify the user requirements, which inform the user experience design. When a prototype or the final product is available, a UXR evaluates its usability, often in a usability test, and communicates their findings.

FED A front-end developer creates products or applications that users can visit and interact with. FEDs use web languages such as JavaScript, CSS, and HTML. An FED produces the design elements you see on an app or website (Hapy Design, 2024).

PO A product owner is an individual who is responsible for the market success of a product.

Important Terms Used in This Paper

Edge case A problem that only happens in extreme situations or at the highest or lowest end of a range of possible values. Examples of edge cases include

- a user unexpectedly pressing two keys within a fraction of a second;

- a user entering an exceptionally long user name of, for example, 260 characters, or a user name containing emojis;

- the system breaks down; or,

- an unexpected internal error occurs.

Method

Our method was inspired by the approach used in the Comparative Usability Evaluation (CUE) studies (Molich, 2020). In these studies, 3 to 15 teams independently evaluated the same website and afterwards compared their results.

Participants

In September 2023, the first author issued a call for participation to colleagues and to a German and U.S. discussion group for UXPs. Eight teams volunteered to be interviewers. Team 5 left the study shortly after signing up because of time constraints. The remaining 10 interviewers are listed in Table 1. They completed 20 interviews, as shown in Figure 1. Team 8 left the study after completing the interviews because of time constraints.

The authors acted as advisors, leaving the teams to carry out the actual interviews. This minimized authorial influence on the way the interviews were carried out, although, classic qualitative analysis claims safeguards to minimize this (Charmaz, 2014). Alternately, it introduced a diversity of different influences from the teams, which could be picked up from a reading of the transcripts.

Participation in the study was free.

Table 1. The Seven Teams and 10 Interviewers Who Participated in the Study

| Name | Affiliation | Team | Lang | Role | #int | Yr UXP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immo Stahl | crossnative | 1 | DE | Interviewer | 40 | 5 |

| Carla Biegert | Centigrade | 2 | DE | Interviewer | 30 | ½ |

| Alessandra Rodrigues Eismann | Centigrade | 2 | DE | Interviewer | 30 | 1 |

| Britta Karn | Centigrade | 2 | Observer | 150 | 8 | |

| Lennart Weber | diconium | 3 | DE | Interviewer | 200 | 13 |

| Greg Hamilton | Born Group | 4 | EN | Interviewer | 500 | 8 |

| Melissa Paluch | Self-employed | 6 | EN | Interviewer | 70 | 15 |

| Andrew Maier | Self-employed | 7 | EN | Interviewer | 125 | 15 |

| Beth Martin | Self-employed | 7 | EN | Interviewer | 100 | 20 |

| Max Scheugl | Self-employed | 8 | EN | Interviewer | 50 | 24 |

* The column “Lang” shows the language used in the interviews: DE-German or EN-English. The column “#int” shows the interviewer’s experience expressed as the number of professional interviews they had conducted before the study. The column “Yr UXP” shows the number of years the interviewer has worked as a UX professional.

Each team recruited two or three FEDs for their interviews. Information about the FEDs can be found in Table 2.

We were happy to learn that some of the participants explicitly appreciated this opportunity to self-reflect on their interview techniques and work processes.

Figure 1. Participant roles in the study. Details about the interviewers can be found in Table 1. Details about the interviewees can be found in Table 2. The Austrian interviewer shown in the last row conducted interviews in English.

Table 2. Information Showing the Versatility of the 20 Interviewees

| Id | Job title | Exp | Current work area | Formative training |

| 1-1 | Sw Eng | 6 | Tool that determines cyber risks | BA: Dual-study track business informatics, Master’s in Sw Eng |

| 1-2 | Sw Eng | 8 | Form editor for insurance comp | Minimal training at university. Largely self-taught: Udemy®, books |

| 1-3 | Sw Eng | 1 | Landing pages business portal | Self-taught: Udemy, trainings, and workshops |

| 2-1 | FED | 13 | Insurance, Industry, Automobile | University degree: Something to demonstrate. Then, continuous further training: certificates. |

| 2-2 | Sr Sw Eng | 9 | Industry, Mechanical Engineering | Gained knowledge through university degree, but also online courses, autodidactic learning, and doing. |

| 2-3 | Sr Sw Eng | 15 | Industry | Has a university degree but does not think that it’s necessary |

| 3-1 | Sw Eng | NA | Insurance | NA |

| 3-2 | Sw Eng | 1 | Manifold | NA |

| 4-1 | Sr FED | 14 | Agency consultant | NA |

| 4-2 | Sr Front-End Engineer | 20 | Agency consultant, E-commerce | On the job, degree in computer engineering |

| 4-3 | Sr FED | 19 | Insurance | Started in graphic design, learned development on the job |

| 6-1 | UX Researcher | 4 | Operations Coordinator – Government | B.S.: University of Pittsburgh, Information Sciences/Studies |

| 6-2 | Consultant/ Freelancer | 20+ | Financial sector | Certifications, such as General Assembly UI Design Fundamentals; AWS Cloud Architecture |

| 6-3 | Front-End Engineer | 20 | Construction, geospatial, transportation | B.S. in Electrical Engineering and Springboard UX Design Certification |

| 7-1 | Sw Eng | 11 | Government tech consulting | Learned at meetups. Web development bootcamp in 2013 – learned Git, Ruby on Rails, jQuery |

| 7-2 | Sw Eng | 4 | Work productivity Sw | Learned HTML, JavaScript, CSS, working with APIs, basic understanding of UI/UX on the job |

| 7-3 | Sr principal Sw Eng | 11 | Customer service Sw | Learned relevant front-end techniques, such as accessible web design and CSS on the job |

| 8-1 | NA | NA | Sw marketing healthcare systems | NA |

| 8-2 | NA | NA | Medical practices | NA |

| 8-3 | FED | NA | Web agency consultant | NA |

* The column “Exp” shows the number of years the interviewee has worked as an FED. NA = information Not Available; Sw = Software; Sr = Senior; Eng = Engineer.

Study Design

The authors created an interview guide for FEDs who work independently of UXPs and another for FEDs who cooperate with UXPs. The interview guides comprised 32 and 47 questions, respectively. Sample questions from the interview guides are shown in Table 3. Both interview guides were reviewed and critiqued by the interviewers before they were deployed.

Table 3. Sample Questions from the Interview Guides

| FEDs who work independently of UXPs | FEDs who cooperate with UXPs |

| A2. Tell me about your work as a front-end developer, with focus on how you create user interfaces. | B2. (Same as A2) |

| A8. Whose job is it to ensure that users can use your front-end efficiently? | B5. Tell me about your cooperation with the UX professionals in your organization. |

| A14. What is the basis for writing user stories and user requirements? | B6. What deliverables do you routinely get from the UX professionals? |

| A18. What techniques do you use to visualize your UI designs? | B10. What do you consider the biggest weaknesses in this cooperation? |

| A23. How do you get user feedback on your product before it is released? | B20. What kind of descriptions of the users, their goals, and key tasks do you get from your UX professionals? |

| A26. Are your products usability tested? | B45. How could your cooperation with UX professionals be improved? |

| A30. I’m looking for user feedback here – from you! What do you think were good points during this interview, and what do you think I could improve on? | B46. (Same as A30) |

Note: The full interview guides are available from the first author.

Each team recruited 2-3 FEDs. There were no restrictions on recruiting. Some FEDs were from the team’s organization, and some were from other organizations. A UX professional from the team then interviewed the FEDs based on the appropriate interview guide (Figure 1). The authors suggested a length of 50 m per interview, considering the amount of information generated by the interviews and what we could reasonably expect from busy interviewers and FEDs. Each interview lasted 25-55 m. Nineteen interviews were remotely conducted, and 1 interview was conducted face-to-face. All interviews were audio recorded, and 17 interviews were also video recorded. The advisors provided a standard form, “Consent to take part in interview.” We believed that all interviewees signed this form, but we can’t be sure because we asked the teams not to return the signed consent forms to us to respect participant anonymity.

The interviewers had to skip many questions because of the limited time available for each interview. In the interview guide, the authors had marked 17 questions for the stand-alone FEDs, and 23 for the cooperating FEDs as particularly important, but it was challenging to find time even for the reduced number of questions.

All interviews were transcribed using TranscribeMe™ software. Eight interviews were conducted in German and then translated into English using Deepl™ software. The transcription software also split each interview into chunks of speech. Each chunk lasted about 30 s. These chunks were the basic unit of analysis for the interviews. Even though the chunks were generated by software, they seemed reasonable, and the authors never felt a need to move text from one chunk to another or to split a chunk into several chunks.

The authors considered the quality of the transcriptions and translations to vary from acceptable to good. Scattered hallucinations and incorrect transcriptions were detected, mostly in places in which the interviewer also had trouble understanding what was being said (according to a review of the original video afterwards).

The transcripts showed that almost all interviewers followed the interview guides closely, and they made reasonable decisions when time constraints forced them to skip questions.

Based on anonymized transcripts, each chunk was coded independently by both the authors and at least 3 interviewers. Six of the 10 interviewers participated actively in the coding process. They coded 2-4 interviews conducted by other teams to learn from other teams. Coding was an ad hoc process based on codes provided by the advisors. The interviewers’ coding helped the advisors identify interesting chunks that the advisors had overlooked.

The authors started by creating some general codes for analysis. The general codes focused on significant concepts and terms, process-related activities, the social environment, quotes that characterized the interviewee well, and good or bad interview techniques.

The second author simulated the expansion and testing of the general codes. He developed a detailed set of expanded codes iteratively, using chunks from all interviews as a training set. He started with the general codes, so that the expanded codes always fit inside the general codes. The point of saturation was defined as the moment when neither of the two authors was able to add another expanded code to the existing corpus in yet another round of analysis. These codes were valuable in creating the developer journey maps.

Here is a summary of our approach:

- The first author writes and distributes a call for participation.

- Seven teams volunteer to be interviewers.

- The authors write interview guides.

- Interviewers review and improve interview guides.

- Each team recruits two or three FEDs.

- Team members interview their FEDs in one-on-one interviews using the appropriate interview guide.

- TranscribeMe software transcribes all 20 interviews from videos in English or German and breaks transcripts into chunks of approximately 30 s.

- Deepl software translates 8 interview transcripts from German into English.

- Based on the chunks, the authors and some team members identify significant concepts and terms, process-related activities, quotes that characterized the interviewee well, and good or bad interview techniques.

- The authors create lists of terms used by FEDs that may not be known to all UXPs, and vice versa.

- The authors create personas from chunks that characterized the interviewee well.

- The authors create an individual Developer Journey Map (DJM) for each of the 20 interviews.

- The authors merge individual DJMs into a general DJM.

Results

During the analysis of the interviews, we discovered differences in the attitudes of, and terms used by, participating FEDs. We summarized the patterns in four FED personas and lists of language gaps between FEDs and UXPs.

We also discovered similarities in FEDs’ process descriptions. We summarized these similarities in Developer Journey Maps and lists of touchpoints between FEDs and UXPs.

FED Personas

The first author carried out an open-card sorting method of all chunks with quotes that characterized an interviewee and placed them into a category (UXQB, 2022). During the open-card sorting method, four archetypal personas emerged (Table 4). The first author then edited the quotes into four persona descriptions. Some of the quotes were used verbatim; others were edited to produce a fluent persona description. Each statement in each persona description can be traced back to one or more chunks; that is, to one or more interviewees.

Table 4. Four Archetypal FED Personas Identified as Being of Interest to UXPs

| Name | Key characteristic | Number of interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| Valentino | FEDs and UXPs respect each other’s skills and communicate well | 10 |

| Frida | Frustrated by her organization’s lack of consideration for users | 6 |

| Carolyn | Does not care about user research | 4 |

| Everett | Sees no need for UXPs because we are all users | 5 |

* Fifteen interviewees match one persona. Five interviewees exhibit characteristics of two personas.

Valentino: “FEDs and UXPs respect each others’ skills and communicate well.”

Valentino is really satisfied with his current position. He appreciates that the whole development process is structured. There is a clear differentiation between people who come up with the concept, create a design, and implement it in code. Throughout the organization, FEDs and UXPs respect each other’s skills and knowledge, and they communicate well. There are no silos.

How UXPs should treat Valentino: Provide compliments and encouragement. “Keep up the good work.”

Frida: “I am so frustrated by my organization’s lack of consideration for users.”

Frida is frustrated because she often has to build front-end software without knowing the context, such as the users and their tasks. She wants to be treated as a respected partner; that is, an engineer, not a worker who obeys orders without asking any questions. Product development should involve cooperation between the client, project management, conceptors, designers, engineers, and UX professionals. Frida says a key problem is that some customers don’t want to spend money on UX because they don’t see the point (yet).

How UXPs should treat Frida: Provide information about the context of use, for example, personas. Invite Frida to comment on the design, showing that they take her advice seriously.

Carolyn: “I don’t care about user research.”

Carolyn values expertise and considers requests for UX research as a sign that an FED lacks expertise. In Carolyn’s view, UXPs are product designers and accessibility experts. UXPs should use their expertise to state workflows, edge cases, and visual and color requirements, which Carolyn then implements.

How UXPs should treat Carolyn: Invite Carolyn to observe usability test sessions and to participate in discussions about the findings.

Everett: “Everyone of us is a user.”Everett thinks of the average user as himself. Everett uses his own experience to infer his users’ needs in relation to whatever it is he’s building. He implements his notions of what a good user experience is because clients rarely know. Everett knows that he doesn’t have a formal education in user experience. But he builds websites for consumers, and he has personal consumer experience.

How UXPs should treat Everett: Invite Everett to observe usability test sessions and to participate in discussions about the findings.

Some interviewees said that they had met all four of the personas in real life. But several of them said that the Everett persona is now in the minority. We wanted to ask all the interviewees for their thoughts on the personas, but we couldn’t because the interviewees were too busy.

Reviewers of the early versions of this paper suggested that there is at least one additional persona: People who have both FED and UXP skills. In hindsight, we could see traces of this persona in some of our interviewees, but no clear examples like we had for the other personas. Merging the FED, UXD, and UXR roles can lead to strong knowledge profiles, which is a topic that should be directly addressed in future research.

More detailed one-page descriptions of each of the four personas are available from the first author.

Language Gaps Between FEDs and UXPs

The transcripts showed that language gaps create difficulties for collaboration between FEDs and UXPs.

Some of the UX terms used by interviewers were unfamiliar to some of the FEDs. Some of these terms inadvertently appeared in the interview guides. Examples of these terms are shown in Table 5. The table can be used by UXPs to avoid the use of these terms in their communication with FEDs or to explain them carefully.

Table 5. Examples of UX Terms That Interviews Showed Were Unfamiliar to Many of Our FEDs

| Term | Authors’ comments |

|---|---|

| Context of use | Some FEDs call context of use demographics. |

| Efficiency | For most FEDs, efficiency means code efficiency and re-usability. In UXP language, this usually relates to how quickly users can accomplish a user goal. |

| End-user | Some FEDs conflate end-user with client or stakeholder. |

| Scenario | All FEDs in this study call scenario a user story. |

| Usability testing | Some FEDs call it production validation testing; others confuse it with accessibility testing. |

| User requirement | For most FEDs, user requirements equate to mandatory features; that is, the application should do what it is intended to do. In UXP language, this usually relates to a determinable condition that helps users achieve a user goal. |

| UX designer | Some FEDs apparently equate UX professional with UX designer even though some of them later mention the role user researcher or UX researcher. |

| UX professional | |

| UX researcher |

Not surprisingly, the interviews also uncovered at least 60 terms that may not be known to all UXPs. Examples of such terms were acceptance criteria, bug bashes, happy path, minimum viable product (MVP), request for comments (RFC), and ticket.

Developer Journey Maps and Touchpoints

In this paper, a Developer Journey Map (DJM) is a depiction of an FED’s interaction with their organization, with particular focus on the interaction with UXPs. A touchpoint is an encounter between an FED and a UXP in which information that influences the user experience is exchanged. In our words, a DJM is a user journey map for FEDs.

Parton (2021) uses the term DJM differently. According to Parton, a DJM is a visualization that identifies the technical path an FED follows and experiences. Parton’s DJM focuses on the products and tools that an FED uses.

To make sense of the large number of process-related chunks that resulted from the interviews, the first author wanted to get an overview of the development processes that FEDs followed to identify similarities and differences. This happened in a two-step process.

First, the first author and team members created an individual DJM for each of the 20 interviews based on chunks that were coded as process-related. Each individual DJM describes the interviewee’s process model.

Second, the first author sorted approximately 600 process-related chunks from the 20 individual DJMs into a general DJM using an open-card sorting method. The first author also looked for chunks that contradicted the general DJM but did not detect any.

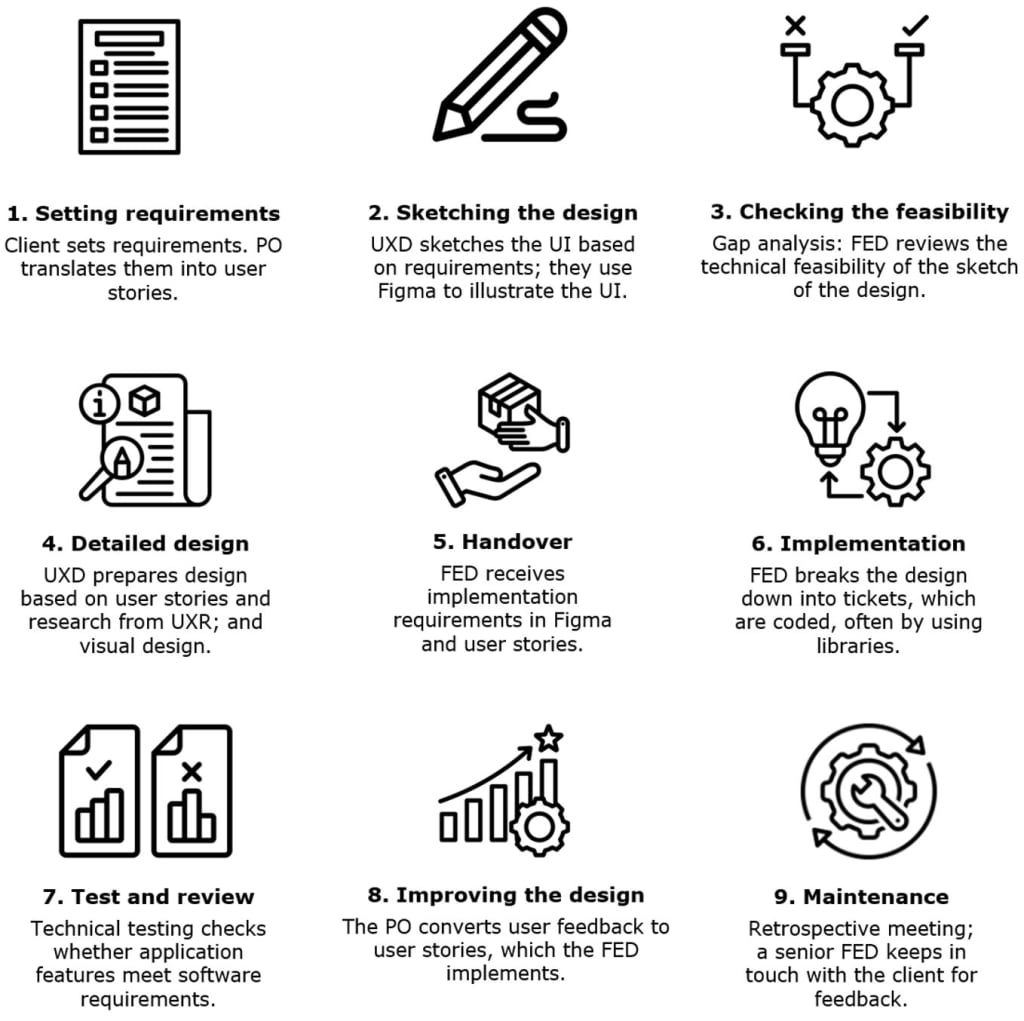

The general DJM is huge and does not fit into this paper, so the first author extracted key points from the general DJM. The key points are shown in Figure 2 and Table 6, which show the phases in the general DJM, highlighting activities relevant to both FEDs and UXPs. Each phase includes facilitators (opportunities for success) and barriers (potential risks). The full, general DJM is available from the first author.

These are the phases in the DJM:

- The client sets the requirements.

- The product owner (PO) translates the requirements into user stories.

- UXDs design the system based on the user stories.

- The design, which is described in Figma (2025) and user stories, is handed over to FEDs.

- FEDs break down the design into tickets.

- FEDs implement tickets by writing new code and tweaking design patterns from pattern libraries.

- FEDs carry out technical testing.

- FEDs improve the design based on results from technical testing, usability testing, and accessibility testing.

- FEDs maintain the system.

Figure 2. An overview of the phases in the DJM. For further details, including facilitators and barriers for each phase, see Table 6. This Figure was designed using resources from Flaticon.com.

Table 6. Key Points from the General DJM

| Phase | Activities that are relevant for FED and UX | F: Facilitator, opportunity B: Barrier, risk |

| Planning | – The project is planned. | F: Ensure FEDs have a seat at the table. |

| Setting requirements | – Client sets requirements, which are a list of web pages that need to be built and a description of the interaction. – The PO translates requirements into user stories. | F: UXPs provide user information, such as personas and task analysis at the start. FEDs often get it from the dailies, but it is useful to know it in advance. B: Some FEDs are not really interested in getting involved in setting the requirements. |

| Sketching the design | – UXD sketches the UI based on requirements; they use Figma and wireframes to illustrate the UI. | F: UXD talks to FED about details they are unsure of. B: Mockups can be misleading because they are free from technical restrictions. |

| Checking the technical feasibility of the design | – Gap analysis: FED reviews the technical feasibility of the sketch of the design; iteration, and refinement. | F: If treated more like a valuable resource and given insight into the user, FED can make features cheaper and more feasible. |

| Designing the detailed user interface | – UXD prepares design based on user stories and research from UXR; UXD talks to PO, looks at competition, etc. – UXD discusses ideas with FED. – Visual designer designs the UI. | F: Figma is a good visualization tool. F: Figma allows several people to work on the design at the same time and enhances communication. F: If FED is involved in the design stage, they can point out potential technical problems. |

| Handing over the design | – FED receives implementation requirements in Figma and user stories. – Requirements include info on what controls are used, what colors and states they have, etc. | F: Figma reduces the required communication between FED and UXD. B: PO, UXD, and client tend to focus on the happy path while FED obsesses over edge cases. B: Incomprehensible or imprecise tickets cause problems. |

| Implementing the design | – FED breaks the design down into tickets. Tickets say what the components must do. – FED uses standard libraries with ready-mades from the client, but sometimes the client wants a certain look and feel, which FED then builds. | F: Development is much easier with a UXP who has done the research and documented the look and feel. F: FEDs like tools that will tell you accessibility issues. B: When tickets change because they were not thought through, it can cause the developer to need to rework. |

| Technical testing and code reviewing | – Technical testing checks whether the application features meet software requirements. | F: Feedback helps FED feel they are making something that is useful. B: FEDs confuse accessibility testing and usability testing. |

| Improving the design -Iterating | – The PO converts user feedback to user stories. – Design changes should happen in Figma, not in code. | B: FED prefers not to get feedback from the client while in the process. If the app is sent to the client while in development to show the FED is doing something, it can raise a lot of issues. |

| Maintaining the system | – FED participates in a retrospective meeting after the project is over to identify issues to improve the process. – After release, one of the seniors keeps in touch with the client for feedback. | F: If feedback is generated rapidly after the implementation work is done, there is a chance to use it. F: FED finds it interesting to see how their work is received. B: Too much feedback is confusing. |

UXPs should pay attention to the quality of touchpoints between FEDs and UXPs to serve their FEDs as well as possible and maintain their flow. Table 7 shows the most important touchpoints between FEDs and UXPs.

Table 7. FED-UXP Touchpoints

| Phase | FED-UXP touchpoints |

|---|---|

| Planning | – Ensuring FEDs have a seat at the table |

| Setting requirements | – Functional requirements and user requirements |

| Sketching the design | – Description of the context of use, in particular personas – User interface visualized in Figma – Descriptions of how elements in the user interface should work – Descriptions of what elements should look like, including states, layout, and colors – Descriptions of edge cases – Accessibility issues |

| Checking the technical feasibility of the design | |

| Designing the detailed user interface | |

| Handing over the design | |

| Implementing the design | – Answering questions from FEDs about the user interface, edge cases, responsive design, and accessibility |

| Technical testing and code reviewing | – Observation of usability test, sometimes referred to as user test |

| Improving the design – Iterating | – Tickets describing necessary changes resulting from usability tests and accessibility evaluation |

| Maintaining the system | – Feedback from users – Tickets describing necessary changes resulting from usability tests and accessibility evaluation |

Table 8 compares the FED journey to the UXP journey, as seen from an FED’s and a UXP’s view. Some of the FED’s tasks in this table were new to the authors, for example, checking the technical feasibility of the design. The UXP journey is based on the ISO 9241-210 standard as described, for example, in UXQB (2022).

Table 8. A Side-by-Side Comparison of the FED-UXP Development Journey

| FED journey | UXP journey |

|---|---|

| Planning | |

| Understanding users and other stakeholders Specifying the context of use: personas and user stories | |

| Deriving user needs from the context of use | |

| Setting requirements | Setting user requirements |

| Sketching, prototyping, and usability testing the design | |

| Checking the technical feasibility of the design | |

| Designing the detailed user interface | |

| Receiving the design from the UXP | Handing over the design to the FED |

| Implementing the design | |

| Technical testing, code reviewing, and eliminating bugs | Usability testing and accessibility testing |

| Improving the design – Iterating | |

| Maintaining the system | Monitoring the user experience as the system changes and data from real users becomes available |

Development Process in General

In this and the following section, we offer additional important insights into the development process as outlined in Table 6, 7, and 8. The insights were offered by the FEDs during the interviews. These insights are also summarized in the subsequent section “Advice for UXPs.”

The FEDs who participated in this study show, time and time again, that they overcome obstacles through good interpersonal communication and recognizing others’ expertise.

In the rest of this paper, quotes from FEDs are shown indented and in italics. They are prefixed with a code, FEDX-Y, that indicates the quote’s origin. X is the team number (1-8), and Y is the team’s interview number (1-3) (Table 2).

Agile

We reviewed the interviews to identify mentions of Agile and key concepts related to Agile. Eight of 20 FEDs mentioned Agile® or Scrum® without being prompted by the interviewer. Nine mentioned sprints and three mentioned daily team meetings, which are important components of Agile.

Three FEDs explicitly said that their development process was a mixture of Agile and Waterfall, but we did not find a sufficient basis to confirm the hypotheses that most actual work processes are more like a traditional waterfall-type design process, nor that business analysis, UX research, and other pre-development activities collide with pure Agile.

FED2-2: In reality, it’s usually the case that major customer XY shouts that they want this change, and then we have to work on it in the next sprint, whether Agile or not. But apart from that, we don’t actually get any direct feedback from end users.

FED6-2: … thanks to the processes and a lot of integration with Agile and sometimes waterfall, … it’s not to a point where “Okay, we’re 40% done this design. You can use it. You can do some stuff with it. If you have any questions, we’re still building this thing.” It’s more, “Okay, we’re 100% done [on] this part. You have any questions, let us know.”

Understanding Users and Other Stakeholders

Some FEDs only know a little about the end-users. They don’t necessarily want or need information about users, such as context of use and user needs. Our personas Carolyn (“Does not care about user research”) and Everett (“Sees no need for UXPs because we are all users”) illustrate this.

FED1-3: We have very experienced developers in our team … And they’ve been doing [UX design] for a long time. And I think that also makes it easier for us, because we don’t need a UX designer so much because we have these skills or this experience.

Other FEDs are interested in the user’s perspective and user research but do not want to be involved in the process other than reading persona descriptions and watching a few usability test sessions. Our persona Valentino (“FEDs and UXPs respect each other’s skills and communicate well”) illustrates this. Eight FEDs spontaneously mentioned personas.

FED8-1: [I] would like to see documents that would enable me [as a] front-end developer to understand who, truly, our users are, what their needs are. Because I do not ever, ever buy this argument that someone truly, without any deep diving, knows who their customer and the users are.

Several FEDs expressed the need for a more robust, bi-directional exchange between FEDs and UXPs:

- Give FEDs more context about users’ needs so that FEDs and UXDs can combine their skills to arrive at an optimal solution.

- Provide more context about end-users’ likely behavior and edge-case behavior in a given task.

- Dedicate more time and effort to processes that cultivate a shared mutual language and understanding between FEDs and UXPs, for example, by familiarizing FEDs with UX terms (Table 5) and familiarizing UXPs with FED terms.

Iterative Development

A fundamental principle for Agile is iterative development; for example, a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) is created during every sprint and user tested afterwards. This was mentioned only briefly by two FEDs, which was surprising given the importance of iterative development.

FED2-2: The project I just mentioned was good because you can really feel the agility, and the things I’m developing this week, I’ll get feedback on next week when it’s looked at. So this proximity is simply a good thing. In other projects, it’s often the case that they’re not quite as agile, which means you develop something, then of course it’s tested, but it takes six months to a year before it reaches the end customer, then they pass their feedback back to the salesperson, who then passes it on to the Product Owner, and a year later you know whether it has really solved the end user’s problem or not.

Iterative development also implies changing requirements, even late in development. Some FEDs consider a barrage of externally imposed design changes as the worst thing that can happen, and yet many FEDs see end-user reactions as important (see the section “Feedback”). This opens up a wider debate about the roles of the UX designer and the FED, which we will not address here.

FED2-3: I think the biggest weakness is rather the [collaboration] with the customer, that there are perhaps contradictions or ambiguities from the customer side from time to time. And then things are implemented and afterwards, it turns out, the customer has changed his mind, and that’s not the fault of us or the company. But yes, then several rounds are made, and I wonder whether this could be improved, whether it could somehow be approached more efficiently, but I don’t know of a solution now.

Feedback

Because the entire process of creating software may seem at times to verge on the chaotic, FEDs are very insistent on the need for informal feedback and easy channels of communication. Meetings must be well-run, and professional relationships must be maintained, but care must be taken to be respectful of the professional expertise of other groups of co-workers in the process. Formal channels, well-defined formal procedures, and agreed formats of specifications would be good, but they can add complexity if imposed irregularly in a chaotic environment.

FEDs enjoy hearing that their work has met with success, but this does not often get communicated to them.

FED7-3: [Feedback] helps me feel like I’m not making something that’s not useful. I think the one thing that a lot of engineers and designers are ultimately afraid of is that they make something that is not useful, or not actually wanted, or worst goes completely unused.

FEDs’ Experiences Regarding Phases in the DJM

Setting Requirements

FEDs are highly skilled in creating software, but they rely on co-workers with UX and design skills to provide them with requirements that they can turn into tickets that they can actualize in sprints. Many FEDs complained that requirements are often poorly formulated.

FED1-1: So, if there is something like a product owner or a specialist department in some form, then [requirements] certainly come from there, but if it is perhaps … very roughly formulated, build this, then perhaps you have to break it down again yourself and ask again in more detail when breaking it down.

FED2-2: So if I’m involved a lot in the refinement, where you prepare the tasks for the next sprint, I have a relatively big influence on that because we write them together with the PO or the conceptor. It’s often the case that they lack the technical mindset a bit.

When the FEDs are faced with implementing vague specifications, some just use their intuitions about what is best.

FED8-1: So most of the time, there were plenty of things in the end when the implementation came into the game that there was, like, a lot of things truly unsaid, and developers mostly have to figure it out on their own. So [the] product is sometimes deviated because so many details, small ones, were not described fully how [they] should operate.

The biggest problem in setting requirements is communicating the dynamic properties of the sequence of states of the application. All our FEDs except FED4-1 mentioned Figma, and most praised it. Although there is a great reliance on Figma, specifications in Figma have to be supplemented with additional information. Even though some organizations use Gherkin (Cucumber Open Source Project, 2024) or other dynamic representations, there is still not a widely recognized solution. These are the two most frequently voiced problems:

- Small but critical features of the design are insufficiently described.

- There’s too much emphasis on screens and not enough on user flow.

Examples of small but critical features are edge cases. The FEDs told us that a significant part of their work is to clarify and implement edge cases. Frequent mentions of small but critical features by our FEDs included animation, conditional logic, and rules around selectors and dropdowns.

FEDs appreciate it if UXPs know enough about front-end development to formulate useful user stories and requirements. Even though FEDs were familiar with requirements, user requirements as understood by UXPs involving user goals, were alien to most of them.

Sketching the Design

Prototypes are used by some FEDs, but not in the way that a UXP would use them.

FED7-2: Sometimes we have to estimate how long our work is going to take. So sometimes it’s helpful to do a really quick prototype to see how complex [the] work is going to be.

Designing the Detailed User Interface

Many FEDs valued UXDs’ expertise in design.

All FEDs, even those who were unsure about the value of UX research, recognized the importance of accessibility. This is because knowledge about standards and guidelines is required, and it’s hard for an FED to predict how people with impairments will react to their product. Eleven FEDs mentioned accessibility without being prompted. Some thought user-centered design and accessibility were the same thing. From a user-centered design point of view, these elements are different and require different approaches, and yet on the topic of testing and reviewing (see the section “Testing and Reviewing”), FEDs emphasize functional testing.

FED3-2: User-centered design is crucial … because something like accessibility has to be taken into account.

FED6-2: In the usability test for front end, I guess a lot of times we do focus on accessibility.

The frequent mentions of accessibility came as a surprise to us. The interview guide did not include any questions about accessibility. No interviewers followed up on the mentions of accessibility. Based on the time limitations, this seemed a reasonable decision to us.

Handing Over the Design

FEDs are happiest when presented with clear specifications of problems to which they can apply their considerable skills. They feel that their input at the design stage would provide these assurances:

- Reasonable solutions to every design problem

- No gaps in the designs that have to be investigated during coding, thus interrupting, halting, or even reversing direction of effort

FED3-1: But in the project, we as developers were not involved in the design process right away, so we sometimes only noticed afterwards where things might have been different or a little better.

Implementing the Design

FEDs rely heavily on code bases and libraries for tried and trusted solutions that they apply and modify in a thoughtful way.

Testing and Reviewing

FEDs rely heavily on functional testing, which is often automated. Mainly, they understand that software quality is defined and delivered by reliability, that is, eliminating bugs and crashes. They like accessibility evaluation because it consists of clear guidelines and diagnoses.

A few FEDs had observed a usability test. More had heard about usability testing, but some confused usability testing with stakeholder opinions or user testing, that is, functional testing carried out by users.

FED4-3: They [the client] have feedback from a former user on staff.

FED8-2: Maybe I think this should be easier or I think this is too complex for the user because we also … have our own opinions. So, it’s also good to give our opinions as users and as developers.

FED8-3: In my country — I’m from Azerbaijan — there’s a saying that ‘no one would say that my yogurt is sour.’ […] Basically it means that for me [my product] is the most usable product ever.

Limitations

The process followed in the research reported here differs from a conventional Qualitative Analysis framework (Charmaz, 2014) in these important ways:

- The authors relied not just on their own views but asked stakeholders (UXPs) to interview FEDs based on the authors’ interview guides. The UXPs later commented on the results, which reduced bias. By having several people who were independent of the authors identify FED participants and serve as interviewers, the study reaches further out as compared to relying on the authors’ networks and focus.

- The interview guides, once formulated, remained static and did not adapt to knowledge gained during the interviews.

- The double hermeneutic method, in which the FEDs that were interviewed would be invited to review and respond to the analysis of their interviews, was not used. This was inevitable because of the design of the research (busy professional interviewers) and the nature of the respondent sample (busy professional front-end developers.)

Both interview guides were too extensive. In an interview lasting 50 m, interviewers cannot be expected to be able to ask 32 or 47 questions plus reasonable unscripted probing questions. However, you could argue that an experienced interviewer must be able to prepare well for an interview so they can manage to address the most relevant questions within a limited, prescribed time.

The interview guides did not include a question about whether FEDs had ever read or used usability reports. However, several FEDs said usability reports were not communicated to them (hence the title of our paper), and that typically, feedback came from informal contacts after release.

The interview guides were not tested in any pilot studies because the authors erroneously believed that iterations among themselves and the interviewers would be sufficient.

The number of interview participants and the sample per geographical region is too small to derive quantitative results or generally valid statements about the occupational groups. However, while the authors agree with this objection, they argue that perfect is the enemy of good. Additionally, recruiting experienced and busy interviewers and interviewees for an unpaid study is challenging.

It has been suggested that the working methods for FEDs in the U.S.A., Germany, and Austria may differ considerably, but we observed no cultural differences between teams from different countries, mainly Germany and the U.S. Other factors, such as company size, may have a considerable influence on work in software development. But we didn’t encounter any examples of this.

Our findings are based mainly on FEDs who develop browser-based systems. It is unclear whether the findings in this paper apply to the development of other types of systems, for example, car information systems and rocket systems. However, by 2018, the difference between browser and desktop systems had already narrowed. Long (2018) wrote “…Therefore, the most important thing is to maintain flexibility. This means selecting a technology stack that can largely be used by both [web cloud and desktop] approaches.”

The bias introduced into the interview data by the participants is a serious concern (Curtis, 1988). These kinds of bias may influence our data:

- Social desirability bias may occur when participants construct answers to conform to the norms of their location or professional group.

- Self-presentation bias may occur when participants describe their role in past events in a more favorable or important light than was actually the case.

- Plausibility bias may occur when portions of an event have been forgotten and are reconstructed with plausible explanations that differ from the actual events. Recalling past events is a reconstructive process.

The transcripts show that few interviewers attempted to detect these biases by probing participants’ answers. Nevertheless, we believe that biases, if any, were negligible and do not materially affect the conclusions based on our findings.

Recommendations for Further Work

The original idea behind this study was to analyze interview techniques used by experienced UXPs. This analysis is ongoing, and the results will be reported separately as the Comparative Interview Study 1, CIS-1.

These are our recommendations for further work:

- Work is required to learn more about the suggested persona who merges the FED, UXD, and UXR roles. This persona may be able to solve many of the communication problems described in this paper.

- Our results should be validated by independent researchers and experienced developers. This applies in particular to the personas, the Developer Journey Map, the lists of terms, and our advice for UXPs.

- A study on the views of user experience professionals on front-end developers would yield more insights. For example, UXPs could interview other UXPs, being careful to avoid bias.

Advice for UXPs

Based on the results, we offer the advice in this section to UXPs who want to improve their cooperation with FEDs.

- Respect your FEDs by treating them as partners and engineers, not workers who obey orders without asking any questions.

FEDs see their skill sets as independent of those of UXRs, UXDs, business analysts, and indeed, project managers and product owners. They often resent having to do the work of these specialists themselves, but sometimes they feel that they have to make the best of a bad situation. They are the ones upon whom the delivery of a product ultimately depends.

FED8-1: At one big company where I used to work, … my position was mostly reduced to be a code monkey. Do not question, implement!

UXPs should cooperate with their FEDs during the design activity. Invite FEDs to comment early on the technical feasibility of proposed designs. Discuss, co-create, and co-critique the desired experience.

FED8-2: So, at the end, I think most developers don’t get really much insight about UI/UX and the users. Most developers are treated like workers, like, “Hey, you have to build this wall. You don’t know what this wall does, but you have to do so.” And I dislike this because I think of ourselves not as workers, but as engineers. And I think this should be a cooperation …

Interviewer: And how could your cooperation with UX professionals be improved?

FED6-3: Definitely breaking silos. And this was, like, just a thing with our team in general. I really wanted to work more closely with the design people because I could see some of the bugs I’ve encountered; I would think, “Oh, this had been found like when they were doing the prototyping.”

- Provide usable information about the context of use and user needs.

Provide usable descriptions of the context of use, in particular users, key tasks, user needs, etc., to allow FEDs to imagine and simulate the desired experience. Produce compelling personas, distribute them, and advertise their availability. Help in translating abstract user needs to user requirements, user interface specifications, and technical implementation details. Sell the descriptions well, but be prepared that some FEDs may not have the time to review them.

Interviewer: What description of the user, their goals, and main tasks do you get from your UX professionals?

FED2-2: I’m going to go out on a limb and say that in 90-95% of the time, none. In other words, until things arrive at my place, they’re actually just features with certain requirements. But why this is the case and which user or user group or which persona is behind it … I can’t remember the last time I received this information and it was useful [authors’ emphasis].

Interviewer: Would you theoretically have access to more information if you wanted to?

FED2-3: If I wanted to, I could certainly get access to the personas or the concepts.

- Support FEDs’ flow state by specifying edge cases and helping FEDs with them.

UXPs should specify both the happy paths and as many edge cases as possible so FEDs do not get their flow interrupted by unconsidered edge cases.

UXPs should provide expert knowledge about accessibility and responsive design; FEDs expect the following from UXPs.

FED4-2: So, I think a detailed description of how a UI element or an interface should work [and] the different edge cases. So, if [the UXD] can describe the different edge cases, it’s quite helpful.

FED7-1: The product and design [should not be] limited by the engineer’s imagination. … We’re constantly talking through things because we just don’t really know what all the possible edge cases are or where the edge cases could be. And so I think that’s why the product and design likes to have engineering there because engineering can help come up with these edge cases or just things we never thought about.

- Be available during implementation to answer your FEDs’ questions quickly, and in order, to avoid interrupting their flow.

Developers are most productive when they are in a flow state (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). Frequent interruptions in FEDs’ flow of work happen, for example, because of vague requirements and specifications, unclear tickets, and unspecified edge cases.

FED6-2: I feel as if [UXPs are] helpful when they’re approachable, really, like if there’s a way to get to them. They’re busy as well.

- Invite your FEDs to observe usability tests and discuss the results with them.

Sell usability tests to FEDs. Invite FEDs to observe usability test sessions so they realize that their opinions about users may not reflect real user behavior. Make it easy for FEDs and other stakeholders to observe usability test sessions as a group because seeing is believing, and watching and discussing makes converts; many good effects flow from watching as a group.

This advice is particularly relevant for FEDs who match the personas Carolyn (“Does not care about user research”) and Everett (“Sees no need for UXPs because we are all users”).

Interviewer: Are your products usability tested?

FED8-1: It’s like a unicorn. Everyone[’s] heard about this. Nobody has seen it. So, let’s answer this question with no.

Offering FEDs access to usability reports, in particular usability test reports, is another strategy to keep FEDs updated on how their work has an impact.

- Communicate user feedback to FEDs, especially aspects of a product that are well received.

FEDs enjoy hearing that their work has met with success, but this is rarely communicated to them.

Test prototypes and Minimum Viable Products (MVPs) with real users to provide quick feedback to FEDs.

FED3-1: … I find it interesting how [the application is] received. In other cases, it was also the case that they first observed the old system to see how it was being used. And on that basis, they then made suggestions as to what should be done differently or how it should be implemented in the redesign so that it works better.

Tips for UXPs—A Summary

- Respect your FEDs by treating them as partners and engineers, not workers who obey orders without asking any questions.

- Provide usable information about the context of use and user needs.

- Support FEDs’ flow state by specifying edge cases and helping FEDs with them.

- Be available during implementation to answer your FEDs’ questions quickly, and in order, to avoid interrupting their flow.

- Invite your FEDs to observe usability tests and discuss the results with them.

- Communicate user feedback to FEDs, especially aspects of a product that are well received.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge strong contributions to this research from the 10 interviewers and the 20 FEDs. Without their generosity, the study would not have been possible.

Special thanks to our colleagues Anker Helms Jørgensen, Chauncey Wilson, Jan Chr. Clausen, Peter Carstensen, Ray Dahl, Rikke Kiilerich, Søren Lauesen, and two anonymous reviewers for their extensive and very helpful comments on early drafts of this paper.

References

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper Perennial.

Cucumber Open Source Project. (2024, April 5). Gherkin. Retrieved April 2025, from https://cucumber.io/docs/gherkin/

Curtis, B., Krasner, H., & Iscoe, N. (1988). A field study of the software design process for large systems. Communications of the ACM, 31(11), 1268–1287. https://doi.org/10.1145/50087.50093

Figma, Inc. (2025). Think bigger. Build faster. Figma helps design and development teams build great products, together. Retrieved April 2025, from https://www.figma.com/

Forsgren, N., Kalliamvakou, E., Noda, A., Greiler, M., Houck, B., & Storey, M.-A. (2024, January 14). DevEx in action: A study of its tangible impacts. acmqueue, 21(6). Retrieved from https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=3639443

Hapy Design. (2024, March 4). Differences between front end developer vs UX designer. Retrieved from https://hapy.design/journal/front-end-developer-vs-ux-designer/

International Organization for Standardization. (2019). ISO 9241-210:2019 ergonomics of human-system interaction – Part 210: Human-centred design for interactive systems. ISO.

Long, M. (2018, September 13). Desktop vs browser: Not just another thick vs thin client debate? Retrieved from https://www.msafocus.com/news/desktop-vs-browser-not-just-another-thick-vs-thin-client-debate/

Molich, R. (2020). CUE-studies. Retrieved April 2025, from https://www.dialogdesign.dk/cue-studies/

Parton, J. (2021, August 5). Developer relations: The developer journey map. Retrieved April 2025, from https://medium.com/codex/developer-relations-the-developer-journey-map-36bd4619f5f3

User Experience Qualification Board (UXQB). (2022, November 7). CPUX foundation level curriculum (CPUX-F). Retrieved April 2025, from https://uxqb.org/public/documents/CPUX-F_EN_Curriculum.pdf