[:en]

Abstract

This study examined various roles in HCI and incongruences between practitioners’ and educators’ perceptions and experiences. The incongruences are articulated through the conceptual lens of Technological Frames (TF), which are evidenced by shared understanding of theory, practice, and a common approach to practice. We conducted 21 interviews with HCI practitioners, educators, and people who both practice and teach. We adopted a template analysis approach with matrix queries to identify similarities and distinctions between the different TFs of these roles. Our findings include incongruences between these roles in how they frame and elicit users’ mental models, how they define HCI success, and their levels of enthusiasm for HCI. Congruence was found in framing communication skills, collaboration, and creativity. We contribute proposals for new requirements to frames and skills within HCI curricula that may help close the gap between education and practice. We conclude that despite some convergence across and within groups, perceptions of the HCI field are still unstable, resembling an “era of ferment.”

Keywords

Technological Frames, HCI Practitioner, HCI Educator, Era of Ferment, Human-Computer Interaction

Introduction

The aim of this research is to provide a better understanding of practitioners and educators in the field of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) by examining who they are, the differences between them, and the potential impact of these differences upon practice, curriculum design, and delivery. This was achieved by comparing the perception and experiences of different roles of HCI practitioners and educators and identifying consensus or variance. A better understanding of their differences will serve the educational experience and strengthen the HCI curriculum, thereby producing graduates who are better equipped to practice in the field. However, the multidisciplinary nature of HCI and its rapid growth against a constantly changing backdrop of technology presents HCI education with several challenges, particularly in curriculum design.

Previous literature highlighted differences between the roles of the practitioners working in the field of system development and HCI. These differences have resulted in criticisms of both HCI practice and HCI education. Gulliksen et al. (2004) note the variety of job titles and differing areas of professional activity, which is echoed by Carroll (2010) who describes HCI as having “no … specified set of practices.” On a similar theme, Churchill, Bowser, and Preece express concern that, despite there being a clear demand for the skillsets, the lack of consensus and clarity in HCI education limits our ability to state the value proposition of HCI education (Churchill et al., 2013b). There have been many studies that survey the practice of the HCI practitioners (Boivie et al., 2006; Clemmensen, 2005; Gulliksen et al., 2004, 2006; Rogers, 2004), and likewise, there have been few studies comparing the differences in attitudes and perspectives between HCI and other practitioners within the field of software development (Lárusdóttir et al., 2014; Putnam & Kolko, 2012). There has been little focus on the differing frames of the HCI practitioners and educators. This research intends to expose this gap by examining the frames held by different roles of practitioners and educators within the field of HCI. The purpose of this study is not to investigate HCI practice and education, but rather how they are perceived in different roles.

Previous research into HCI education concentrated mainly on the curriculum, pedagogy, and the gap between education and practice (Churchill et al., 2013a; Douglas et al., 2002; Hewett et al., 1992). Earlier studies by Churchill et al. (2013b) surveyed those in practice and those in education about the practices and underpinning philosophies of both education and practice to identify a global curriculum. Churchill and colleagues reported that what the practitioners and educators value is not always the same. Our study augments differences between educators and practitioners, including those who both educate and practice. The research question that this research addresses is: How does the frame of the HCI practitioner or educator vary from role to role in respect to their background, what is valued, and their concerns and issues?

Theoretical Background

HCI Practitioners and HCI Educators

Studies comparing HCI practice and HCI education have found that practitioners and educators don’t always value the same things. While design and empirical research methods are highly valued by all participants in these studies, there are apparently differences between the groups regarding what is valued in HCI teaching. In the study by Churchill et al. (2013b), industry practitioners were found to value topics with more immediate application and relevance such as change management and product development; they did not value topics such as health informatics or ubiquitous computing. Conversely, academic researchers and educators rated ubiquitous computing highly and change management low, perhaps reflecting the relative research opportunities associated with the topics. A more recent study (Churchill et al., 2016) noted further differences between what students, academics, and industry professionals value. Students valued topics closely associated with computer science such as robotics and machine learning, academics valued discount usability techniques, along with more generalized topics such as statistics and computer-supported collaborative work to support research activities, and industry professionals valued topics directly related to practice such as communication and business, alongside HCI topics like wire-framing and information architecture. There is considerable evidence for differences between HCI practitioners and educators, but it isn’t clear why we see these differences and what the potential overlaps are between the different perspectives.

Technological Frames

A Technological Frame (TF) is a cognitive device that allows an individual to make sense of technology in a particular context by structuring their previous experiences and knowledge (Lin & Silva, 2005). We chose the conceptual framework of TF because it provides a set of categories to compare views and experiences across a wide array of actors (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008). What is common for definitions of TFs (Bijker, 1987; Orlikowski & Gash, 1994) is that the interpretation of technology varies from group to group. Different groups have a different perspective of the same phenomenon, but within a particular group, perspectives and interpretation of technology are shared. This shared understanding structures their interaction, application, value, and appreciation of concepts according to their degree of inclusion within a particular frame. As people make sense of technology, their understanding of that technology increases.

TFs offer a framework to systematically analyze perceptions of members of the same social group, for example, educators, and compare them with the perceptions of another social group, for example, practitioners. TFs help explain the differences between the groups. As a body of knowledge with tools, skills, and procedures (Britannica, 2021; Merriam-Webster, 2021), HCI is the technology in question. In the context of this study, there are no bound, tangible artifacts; there is an emphasis on the tools and methodologies utilized to develop a deliverable, rather than the deliverable itself, which may be either a physical or digital product or documentation (Clemmensen, 2005). In situations in which various social groups, that is different roles of professionals, have alternate views of the same technological area such as HCI, a frames perspective can support the conceptualization of these differences.

Much of the TFs literature centers on the implementation of information systems within an organization. We, however, consider TFs in a wider context. TFs derive from the Social Construction of Technology (SCOT) (Pinch & Bijker, 1987). SCOT describes the development of technology as an interactive process, shaped by social factors and various social groups with a shared interest in a particular technology; it may result in different social groups interpreting the same technology differently (Pinch & Bijker, 1987). There are differing definitions of TFs and technology within the literature (Bijker, 1987; Davidson, 2006; Gal & Berente, 2008; Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008; Orlikowski & Gash, 1994; Pinch & Bijker, 1987) and differing applications of the theoretical framework. Although the implementation of an information system implies a project, which is a temporary venture with discrete deliverables and a clear start and end, HCI practice is not a project. HCI practice, like other technology practices such as programming, necessarily evolves to satisfy the changing needs of the face of technology.

Kaplan and Tripsas (2008) discuss TFs in the context of evolutionary models of technological change. They use the term “technology” in the context of a particular physical product, such as typewriters, to include the physical manifestation of knowledge as well as the embodied knowledge. There is no physical product in the case of HCI practice, but there are some parallels which can be drawn if the emphasis is on the tools and methodologies utilized to develop a deliverable, rather than the deliverable itself.

Kaplan and Tripsas identify three key sets of actors whose TFs of reference are likely to be diverse, namely producers of technology, users of technology, and institutional actors (stakeholders such as government bodies, user groups, standards bodies, and other organizations with influence or regulatory power). They extend the conceptualization of framing to differentiate the frame of the competing actors, specifically producers, users and institutional actors, and the collective frame that emerges as a result of the interpretations of those actors. They argue that it is this collective technical frame that affects the direction of technological development; the diversity of the position and the priorities of the different actors may lead to conflicting issues and political machinations to establish predominance in the industry. Competing frames between the actors may impede the development of a dominant collective frame, but unless the conflicting TFs are resolved, a dominant design may not emerge from the process.

TFs provide a cognitive lens to the standard technology cycle (Anderson & Tushman, 1990; Tushman & Rosenkopf, 2008) to explain changes in technology that cannot be predicted by economic or organizational factors alone that result from their technology lifecycle model. The first two phases of the technology lifecycle model, the “era of ferment” and the convergence on a dominant design, are pertinent to our argument.

During the “era of ferment,” new technologies emerge. However, actors must make sense of new technologies while new TFs are being created. Because the TFs do not yet exist, actors make sense of the new technologies by referencing similar existing technologies, prior experiences, or prior influences so these TFs may be diverse.

The phase following the “era of ferment” is described as convergence on a dominant design. During this phase, producers often adopt the role of sense-makers of the technology, and in the process of endorsing the dominant design, thereby consolidate the position of the dominant technical frames. However, prior to the adoption of a dominant design, conflicting frames need to be resolved. The SCOT stance is that this is influenced by political and organizational issues as well as technological concerns (Abdelnour Nocera et al., 2021; Anderson & Tushman, 1990), which is reflected by Kaplan and Tripsas (2008) who suggest that the dominant design originates from those actors who strategically promote their TFs and their preferred technology.

TFs provide a narrative of evolutionary models of sociotechnical change (Bijker, 1995; Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008), identifying three key sets of actors whose frames of reference are likely to be diverse, namely producers of technology, users of technology, and institutional actors. A collective frame emerges because of the interaction of these three groups, which shapes the direction of technology. Thus, TFs place the focus on understanding the social, political, and technical processes and products shaping technology from the “ferment” phase to the more stable phases. However, as indicated and illustrated by Bijker (1995), technology can always become destabilized, and dominant designs (to use Kaplan and Tripsas’ terms (2008)) can become non-dominant because of the changing technical, social, and political environment. TFs are therefore a conceptual tool to make sense of how these forces unfold across the frames of different, significant groups.

Technological Frames among HCI Practitioners and Educators

Of particular interest for understanding the TFs of HCI practitioners and educators are the varying reports of HCI practice, the skills required, and the attitudes toward practice. Discussion of tools and methods is part of this, but the focus is on the frame of the practitioners and educators, their attitudes, their values, and differences between the roles. More than a decade ago, several surveys of practitioners, particularly within the Nordic region, provided useful snapshots of the technology of HCI at that time (Boivie et al., 2006; Clemmensen, 2005; Gulliksen et al., 2004, 2006; Rogers, 2004). For example, a study by Gulliksen et al. (2004) of practitioners working in industry and in academia indicated that only around half had formally studied HCI and the rest were either self-taught or benefited from on-the-job training; many of his respondents had transitioned to HCI from other roles, such as developers. These earlier surveys provide accounts of usability practices within the system development lifecycle, success factors, obstacles to usability practice, and the personal skills required of a usability professional (Boivie et al., 2006; Gulliksen et al., 2004). Desirable qualities of the practitioner were framed as communication skills, the ability to work as part of a team, networking skills, being both analytical and creative, and having the necessary technical skills and knowledge (Boivie et al., 2006; Clemmensen, 2005). More recently, Churchill, Bowser, and Preece’s (2013a) survey presented similar findings, with 68% educated in a related field and 47% having formal HCI education.

HCI practitioners work with other disciplines within the system development lifecycle, and multidisciplinarity is evident within the field of HCI itself. For example, methods used may be grounded in psychology, engineering, or design practice with different roles preferring different methods, dependent on their work goals. It follows, then, that just as there are differences between HCI practitioners and other members of the system development team, there are likely to be role differences within HCI practice. These roles have different disciplinary backgrounds, different contexts of practice, and different goals, yet little is known about how they frame the discipline of HCI or how they frame the other stakeholders that they work with. For example, although Gulliksen, Boivie, and Göransson (2006) discuss the frame of the usability practitioner in the context of their roles and skills, and although they do provide some discussion of the attitudes of the practitioner, this frame is generalized within the context of system development. The exception to this is the reporting of the usability practitioners’ attitude to developers, who are disparagingly referred to as “geeks.” This lack of respect is described as an impediment to the required changes in practice. Furthermore, when Clemmensen (2013) discussed Danish usability specialists’ interest in theory and use of methods, he did not differentiate between the different roles of HCI practitioners and educators. One exception to this is the work of Putnam and Kolko (2012) who found designers to be more empathetic, but UX centric practitioners are more likely to refer to user-centred design principles.

The concept of usability may be central to the varying HCI roles. Hertzum and Clemmensen (2012) analyzed what usability practitioners understand by the term usability, finding that they are more focused on goal achievement (efficiency and effectiveness) than on the satisfaction (experiential) element of the ISO definition. This was followed by an analysis of the differing perspectives of usability from three separate viewpoints: that of usability practitioners, system developers, and users (Clemmensen et al., 2013). This study identified some differences between usability practitioners and the other groups. Usability practitioners were found to concentrate less on context related UX than the user group. However, this is unsurprising and can be explained by the goals of their functional role; users have a role related to task completion, so they will naturally be more focused on the context-related UX. This study found that usability practitioners focus more on user-relatedness and subjective UX than either the developers or the users; this contrasts with the findings of Hertzum and Clemmensen (2012) who found less of an experiential focus on the part of usability practitioners.

In summary, the number of practitioners benefitting from specialized education has not changed over the years. Around half have formally studied HCI. Multidisciplinarity, which is core, is evident in the collaboration between other members of the development teams. Usability and a user-centred approach are seen as fundamental to the HCI function. The emphasis of this varies, however, dependent on the role of practitioners and the goals of their tasks. What is increasingly valued, however, may be what is required to support the role: communication, teamwork, and networking skills; the ability to be both analytical and creative; and appropriate technical skills and knowledge.

Methodology and Research Design

Our methodology for this research is informed by theory and uses a qualitative interpretivist approach that relies on participants’ co-construction of central categories in the study.

Participants

The target population of this study was participants who were sampled based on the emerging theoretical constructs of HCI practitioners, educators, and those who are both, practitioner-educators. The sample was purposeful (Gentles et al., 2015) because the categories of HCI roles of practitioners, educators, and practitioner-educators were developed throughout the data collection period. Purposeful sampling is defined by Yin (2010) as “the selection of participants or sources of data to be used in a study, based on their anticipated richness and relevance of information in relation to the study’s research questions.”

The study was done during a two-year period as part of the PhD dissertation research of one of the authors [source not cited for anonymity]. Participation was invited either directly, for example by canvassing conference attendees, or indirectly via LinkedIn discussions and specialist mailing lists, thereby restricting respondents to those who have an interest in HCI. General requests to participate in this research were posted via the following LinkedIn groups: SIGCHI, BCS Interaction, the User Experience Network, Usability Matters.Org, User Experience, UX Pro, UXID Foundation, UX/HCI Researcher, UX/UI Designer, and UX Professional. In addition, emails were sent to several mailing lists including the British Computer Society HCI Specialist Interest Group, the London Usability Group, the ACM Computer Human Interaction Special Interest Group, and the User Experience Professionals Association.

A total of 21 participants at all stages of their career were included from these locations: 9 USA, 5 UK, 3 Netherlands, 1 Germany, 1 Greece, 1 Canada, and 1 Australia (Appendix 1). Each participant was interviewed once. The initial set of interviews concentrated on practitioners working within HCI in industry. Subsequent interview blocks also included both, practitioner-educators, who worked within HCI in industry and taught HCI as external teachers at a university or as a commercial trainer. Finally, the category of educators who have a primary HCI role as teachers at a university were added to the invitations. This resulted in 21 interviews, consisting of 8 practitioners, 5 educators, and 8 practitioner-educators with interview lengths ranging between 27—70 min.

The Interview Process and Questions

Depending on the location of the respondent, the interviews were conducted via video call, phone, or face-to-face. The audio of all the interviews was recorded, and the audio file was uploaded to a password-protected cloud storage space. The transcripts were checked for accuracy and anonymized with pseudonyms to replace any potentially identifiable references to individuals, organizations, or locations.

The interview questions were designed to answer whether the frame of the HCI practitioner and educator varies from role to role in their backgrounds, what is valued, their concerns and issues, and the question of what the implications for the curriculum are. Three versions of the interview were produced: one for practitioners, one for educators, and one for practitioner-educators. The interviews were piloted with a few experts.

Practitioner Interview Questions

The interview started with background such as age, level of education, prior experience, highest academic qualification, route into the field, and the length of their experience in the field. The next part of the interview focused on the HCI practitioner role in the field. They were asked what the terms HCI and UX meant to them and whether they had formally studied HCI, either in an academic course or a commercial training course. Following that, a set of questions concentrated on practice to ask whether they used particular tools and techniques and whether they had formally studied them. To support the interview, we used a list (Figure 1) of tools and techniques that we derived by examination of four HCI textbooks commonly recommended as essential reading for students of HCI in the UK, three of which appear on the SIGCHI list of standalone textbooks that commonly support HCI education globally (Benyon, 2014; Sharp et al., 2019; Shneiderman, 2010). These tools are also documented as part of professional UX courses (Interaction Design Foundation, 2022) and the syllabus of professional certifications in UX (BCS, 2018). The intention was threefold: to put the interviewee at ease, act as a reminder for later discussion, and check whether the curriculum reflected current practice. Initially, the interviewees were asked for yes/no responses because practice would be covered in more detail later in the session. However, it emerged that the interviewees often wished to expand on their response, so as the interviews progressed this was not discouraged. This section of the interview concluded by asking the interviewee to reflect on the aspects of their education or training that prepared them for their role.

The next section of the interview concentrated on their current practice and consisted of open questions to explore the varying reports of practice, the various career paths, and the variety of roles within the field. Questions such as, “How do you elicit requirements,” and, “Which tools do you prefer (and why)?” together with questions targeting success and failure provided a broad framework for discussion, with the open nature of the questions allowing the interviewee to choose the direction of the conversation. We wanted to explore their values, priorities, concerns, and issues. The final question for this section was included as a check, “If you could change anything in the way you do your work, what would that be and why?” Interviewees had an opportunity to highlight any other concerns and issues.

Educator Interview Questions

The first part of the interview covered the same areas as the practitioner interviews. The next set of questions explored curriculum delivery, the position and perception of the discipline within the educational institution, and the priorities given to including HCI content when delivering the curriculum. The goal of this set of questions was to explore the esteem with which the discipline is regarded within the organization by probing the reasons why HCI content is delivered and how it is framed within the institution. This allowed us to examine which aspects of the subject are considered most important.

To test whether the curriculum matched the practice, and the influence of textbooks on the curriculum, educators were asked to consider their teaching practice. They were offered the same list of tools and techniques. They were asked whether these topics were taught, which areas were framed to be most relevant by academics and students, which topics were most satisfying to deliver and study, and whether there was a mismatch between what the student valued and what educators valued.

Next, educators were asked to reflect on practice in the field. The topics covered in this section were very similar to the questions posed to practitioners. Educators were asked about the tools practitioners use, prefer, and value and about practice in HCI projects and the measure of success or failure. Whereas these questions were posed to practitioners to explore their values, priorities, concerns, and issues, in this case they were posed to educators to probe the gap between education and practice to explore educators’ perception of practitioners. To some extent, this section of the interview focused on educators’ responses on the practice. The latter parts of the interview covered the same area and structure as that of practitioners.

|

This was the final list presented for supporting the interviewees: Focus groups Observations Interviews Participatory design Remote usability testing Eye tracking – taught Low fidelity prototyping Paper? Wireframing Personas Scenarios Card sorting Discount usability Heuristic evaluation? Walkthroughs Wizard of Oz? Mental models Model based evaluation Task network models |

Figure 1. List of tools and techniques referenced.

Practitioner-Educator Interview Questions

The framework for practitioner-educators combined the questions detailed above, with the additional question of which of the two roles they would consider their primary role. The definition of what constituted both was variable to include many practitioners who mentor or deliver training courses to colleagues who also consider themselves both. Interview questions were tailored to suit the particular circumstances of each interviewee. The full interview scripts are in Appendix 2.

The Analysis Approach

A thematic approach was adopted for the analysis of the interview data, making specific use of the Template Analysis method (King, 2004). The flexibility of Template Analysis allows not only an inductive approach to discover emergent themes, but it also acknowledges the existence of explicit themes deriving from the research questions and the interview structure. Qualitative analysis software (NVivo 10™) was used to support the analysis of the data. Unlike grounded theory, Template Analysis (King, 2004) is not a methodology but rather a flexible style of thematic analysis that does not depend on particular ontological or epistemological assumptions. The Template Analysis method provides guidance; however, it is not designed to be rigid in its application but should be adapted as appropriate for the research design. It facilitated the identification of themes across a data set. However, unlike the grounded theory approach, we had some a priori codes mapped directly from the role constructs. Furthermore, unlike Braun and Clark (2006), whose thematic approach of three levels of analysis consisted of descriptive code, interpretive code, and overarching themes, we did not differentiate between interpretative and descriptive themes or any particular number of levels of coding. Instead, we used a flexible approach by focusing on areas of our interviews that provided more interest or were closely related to our research question. We returned during our analysis to areas of interest and dug deeper into those areas that were of particular interest (Gibbs, 2012).

The first template was created from a subset of the dataset rather than coding the whole sample. Once a common pattern of codes emerged, these codes were organized into themes, and we assembled them into meaningful clusters and established sub-themes; this formed the first version of the template. Subsequent transcripts were coded with the template in hand to check whether the data could be encoded to one of these themes or whether new ones were needed. We aimed to keep the themes relatively distinct from each other, following the recommendation by Template Analysis to avoid extensive blurring of boundaries between themes, though some overlap is inevitable (King, 2004).

Each candidate theme (code) was manually arranged into categories and subcategories, with additional codes created as potential themes emerged (Figure 2). This was a reflective and iterative process with constant reference back to the research questions, the literature, and the interview transcripts. Each code was a cluster of relevant interview excerpts typically covering between one and three phrases.

Figure 2. Development of themes from candidate codes.

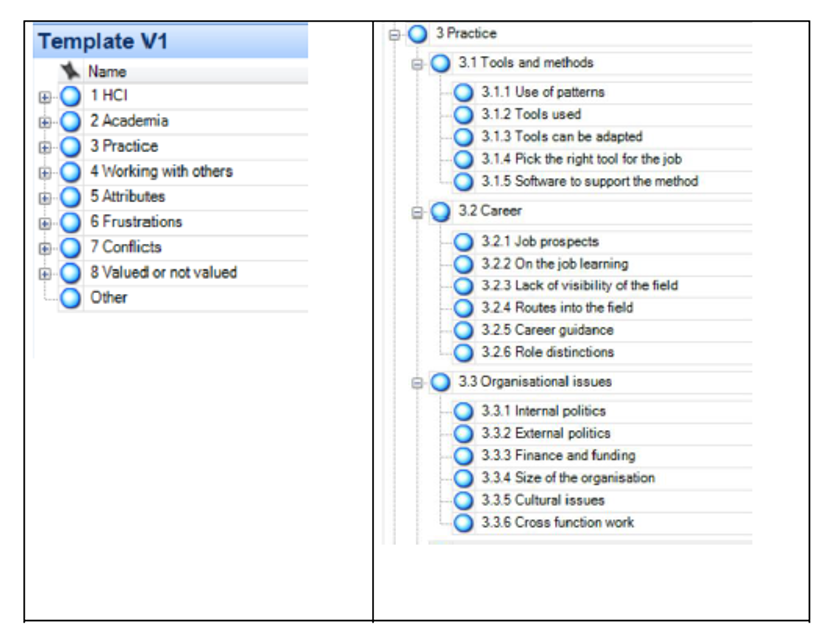

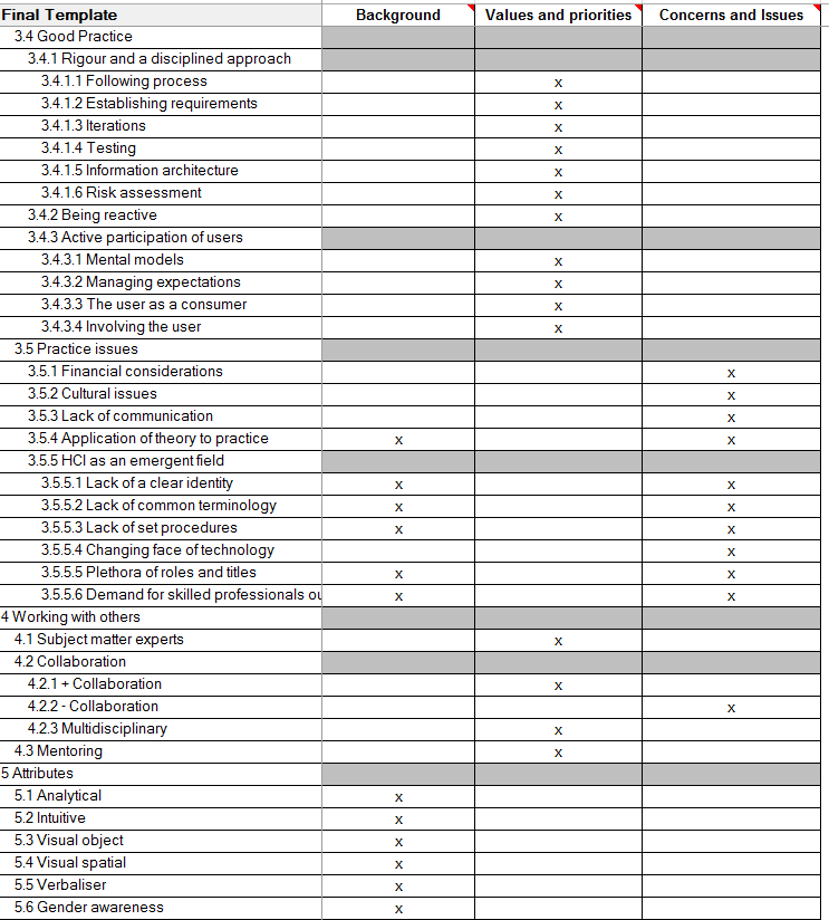

Once the initial template was stabilized, this tree structure was reproduced in the qualitative analysis software (Figure 3). For each iteration of the template, we used the memo facility to support reflexivity. Four more iterations followed until saturation point (for a discussion of sampling, see Gentles et al., 2015). The full mapping of themes and research questions resulted in a total of 59 high-level codes. The distribution was 18 background, 30 values, and 21 concerns and issues (Appendix 3).

Figure 3. Development of themes from candidate codes.

There is no universal consensus regarding which quality checks should be undertaken for qualitative research. King (2018) suggests a number of approaches may be appropriate when using Template Analysis. For this study, it was not possible to have a team of researchers independently scrutinize the analysis of the data; the template developed was reviewed and discussed during supervisor meetings. These meetings encouraged reflection and ensured that the focus of the analysis remained on the research questions. To support this, notes were made of the process and rationale for each version, which provided an audit trail of the process. Additional quality checks included checking the transcriptions against the original audio files.

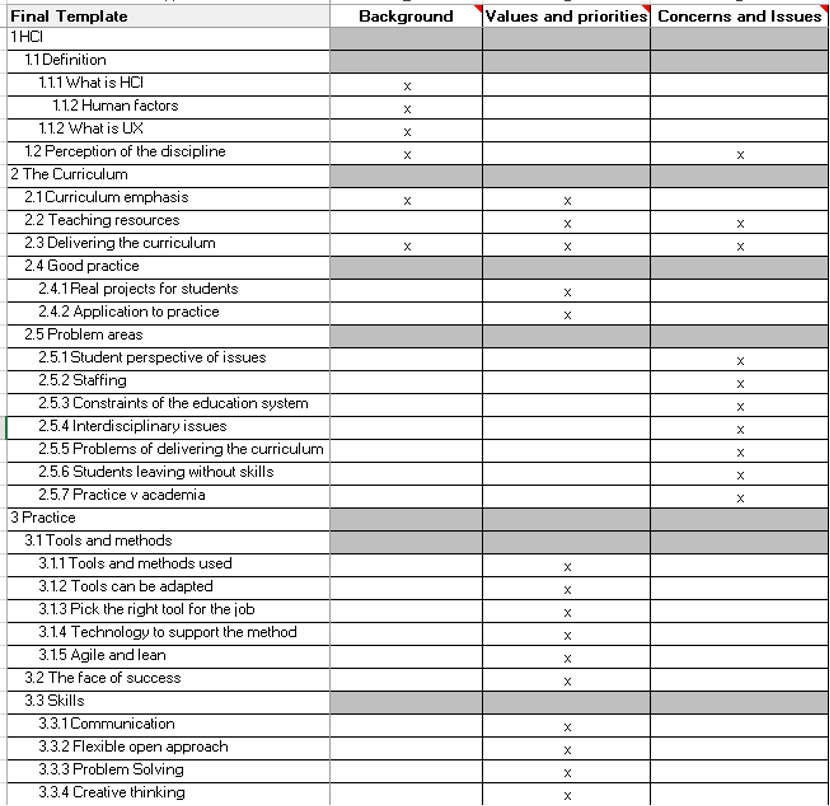

Most of the themes were derived inductively, and these did not always map neatly to the areas of consideration for our research question (background, what is valued, and concerns and issues). To address this, and to facilitate the discussion, each of the themes was mapped to one or more of the areas of research questions. Furthermore, a classification was created that assigned each respondent to one HCI practitioner and educator sub-role (Appendix 1).

To analyze how TFs were distributed among HCI practitioners and educators, we ran matrix queries that incorporated these roles. Thus, it was easy to see whether the responses came from a number of sources, suggesting consensus, or perhaps from one interviewee with strong opinions on a particular subject.

Interview Findings

HCI Practitioner and Educator Roles and Sub-Roles

Educators were identified as those who educate in an academic setting [E], [Ed], and those who educate within practice as a mentor or trainer [Tr], even though we did not interview anyone who was solely in the latter category. Trainers were included in the category for both practitioner-educators (Appendix 1). The identification of practitioner sub-roles indicated more diversity and emerged naturally from the interviews: designer [D], user researcher [UR], and developers and engineers [SD]. The sub-roles are very different with designers being associated with the interface, user researchers being framed to be broader than that of designers, and developers and engineers described in stereotypical terms with the suggestion that HCI does not come easily to them. Interestingly, although one of the principal roles of the respondents was user experience architect [UXA], this particular role was not a topic of discussion during the interviews. These sub-roles were identified during the interviews and as consequence of the purposeful sampling we conducted. Practitioner and educator roles are not treated as mutually exclusive; several participants interviewed engaged in both.

The role of designer [D] was very much associated with the interface itself, and although the job titles do not necessarily differentiate, it includes visual design and interaction design, with some designers specializing in one or the other, or both. Mila [UXA] and an academic educator [Ed] stated that they had visual designers who develop high-fidelity prototypes, but said, “I’m not a visual designer… I can do some interaction design.” Roger, user researcher and academic educator [UR, Ed] had friends who are visual designers and said, “All they do is churn out Axure™ prototypes day in, day out.” Design was viewed as going beyond the immediate interface with both Delia [D] and Lotte [UR] talking of design in the context of solving a problem, and Larson software developer and educator [SD, Ed] stated that HCI design extends beyond software, posing the question, “At what point is something HCI, and at what point is it product design?” Larson continued to say, “Most product design is related to physics… It’s only when designers try to fight against physics, we end up with objects we’re not too sure how to use.”

The role of user researcher was framed broader than that of designers. Some user researchers were involved in some elements of design, in particular interaction design, but not implementation. Others focused solely on the research. Lotte [UR] stated, “I don’t actually design,” and neither did Roger [UR, Ed], although he stated that this is not always the case: “We really kind of stay away from design. [But] Most of my friends in the field do aspects of that.” Their input into the project starts earlier in the project lifecycle, and the focus of their work may be to identify requirements or identify issues. Larson [SD, Ed] was the only respondent with a software developer role, and he made several references to his fellow programmers, as “nerds,” who “just want to get on with the technology and see the user as this kind of irritating distraction,” and who are “very uncomfortable about doing a lot of the touchy-feely stuff.” Larson continued with an interesting observation of the challenges of the typical student in a computer science course with the materials we use to deliver the HCI curriculum: “I think one of the problems with a lot of HCI courses is they tend to assume that the emotional and intellectual make-up and the cognitive style of the programmers is similar to that of psychologists or the people that tend to write the interaction books” (Larson, [SD, Ed]).

What Is Valued

Variance and congruence were observed between the TFs of practitioners, educators, and sub-roles with practitioners’ frame: differences between UX architects and user researchers when considering mental models, differences in the curriculum of educators and those who both teach and practice with Agile methods, and differences in how user researchers, UX architects, designers, and educators view success. In deciding what is valued, we identified value statements made by participants when discussing what contributed to successful or unsuccessful projects, not as result of quantification. Our approach didn’t use quantification; our approach to analysis was similar to that followed by authors using TF as a conceptual framework (Karsten & Laine, 2007; Lin & Silva, 2005; Olesen, 2014).

Valued Skills

When considering the skills required, there was consensus. Although familiarity with tools and methods was desirable, the key skills that were most valued are generic: communication, collaboration, problem-solving, creative thinking, and having a flexible and open approach. Effective communication was seen as key to successful practice. For example, when Delia [D] was asked what from her education prepared her best for practice, she talked about the interviewing and listening skills obtained during her master’s degree in Mental Health Counselling training rather than her Master’s in Computer Science.

The importance of the above-mentioned skills also fed into the “working with others” theme, in which collaboration and teamwork were also highly valued by participants. Within practice, one of the indicators of a successful project was evidence of collaboration. The employment status of the practitioner can also affect collaboration, with some independent user experience architects and designers reporting negative experiences. Some differences were noted between the roles when discussing collaboration. Although all roles discussed some aspects of acting as an interface, user experience architects and user researchers discussed collaboration in a broader context than designers. This included the tools used, the involvement of industry, and some of the more abstract aspects of collaboration, such as skills-sharing and the positive emotions evoked. The tools used to facilitate collaborations were digital and cloud based, not specialist tools associated with HCI. Mila [UXA, Ed], Clara [UR, Ed], and Lucy [UR, Tr] mentioned tools such as Evernote®, One Note™, and Google Docs™. There is evidence of collaboration outside of the system development team and the immediate user community, evidenced by Agnete [UR, Ed], who discussed the importance of collaboration with industry for academia: “The relationship between industry and academia, they really help in Canada,” and Kenneth [UR], who works with the wider business community, noted: “We’re interested in learning about differentiations between business types, so we use interview questions to learn about how different types of businesses conduct business differently.”

Designers discussed collaboration in the context of acting as a facilitator or interface between the users and acquisitions, the users and business analysts, and the users and marketing respectively. It is also clear that the benefits of collaboration go beyond the obvious facilitation of the development process. Several interviewees mentioned the mutual respect of colleagues and the feeling of being valued resulting from sharing skills. Finally, whilst collaboration is viewed as beneficial to a project, conversely, when it is lacking, it is often an indicator of a failing project. This appears to be more apparent in Agile projects and those involving independent contractors or freelancers.

Multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary cooperation across roles and skills was recognized by several interviewees as contributing to success, but it was not without its own set of challenges as each disciplinary area tends to compete to have their own requirements satisfied.

Problem-solving and creativity were core elements of all the roles. This went beyond providing a design solution and included risk management strategy, as Delia [D] pointed out: “Identifying the problem early, having a strategy to address it.” Working in a multidisciplinary environment certainly appeared to support problem-solving. For example, Kenneth [UR] explained that, as a result of his film industry background, “being a creative person in an engineering environment” kept design options open and allowed him to benefit from the perspective of the engineers.

Valued Tools and Methods

Practitioners reported a range of tools, both hardware and software, and methods such as personas, Agile practice, and (elicitation of) mental models. These were all coded in theme 3.1 “tool and methods” of the template (Appendix 3). Tools and methods generally were appropriate for the particular role of practitioners. However, the variety of tools adopted did suggest that a dominant design does not yet exist (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008). Differences were also noted between the TFs of user researchers and user experience architects when discussing mental models. User researchers used mental models to understand and manage the expectations of the user, and the user experience architect used mental models for task analysis of different end users and to communicate the differences.

A diverse range of tools was reported. The list included Axure, Optimal Workshop™, OmniGraffle™ and usertesting.com®, as well as older technologies such as Adobe® Flash® and Director. However, paper and pen, pencil, and sticky notes are amongst the most widely used tools, and tools such as PowerPoint™ and Excel™ are used for design and tracking activities.

One particular method that was mentioned by several interviewees was the elicitation of the users’ mental models. UX architects and the user researchers both discussed the elicitation of mental models of the end users to support effective communication, but incongruences were observed between the frames of these two roles. This incongruence manifested itself in the emphasis of the application. For UX architects, the elicitation of mental models was important to support the task analysis of different categories of end users and to communicate this. For user researchers, the perspective was slightly different to that of user experience architects, and the elicitation of mental models of the user is closely associated with the expectations that user has of the proposed system with difficulties arising when the user’s mental model is not satisfied.

The interviewees may value a tool, but they will only select it if it also adds value to the task. For example, Eli [UXA, Tr] will not use personas when he is designing for the general public “because the persona is the entire world,” but in the “corporate software business or business software environment, personas are very well defined and if you know that if you’re building something for an accountant versus an HR manager there’s a very big difference.” Kenneth [UR] makes use of usertesting.com because “our target market is a similar set as the people we find on UserTesting… so it’s easy for us to find small business owners, or sole proprietors, out of a set of folks who typically do a lot of work from home.”

It is clear that a dominant design (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008) has not yet emerged. Practitioners often adapt methods to suit their needs, and this practice is evident for experienced and newly qualified practitioners. Several practitioners mentioned developing their own, tweaking existing heuristic sets, and adapting or developing methods as required. Several practitioners called for a flexible approach when applying conventional methods.

Curriculum Focus

What is valued by educators is reflected in the focus and delivery of their curriculum. Educators mentioned three main areas of curriculum emphasis: cognitive psychology, interaction design, and evaluation techniques. Helen [E], Tina [E], and Terry [E] all include interaction design in their undergraduate curriculum. Antonina [E] puts “a lot of emphasis on design, design cycle, and design processes, from concept generation to implementation and evaluation. I put a lot of emphasis on evaluation, different evaluation techniques.” This is true particularly for the undergraduate curriculum, and this is echoed by Helen: “I really, really try to focus on the process, the user centred design process, and the importance of research and evaluation at every step of the process.”

Where HCI is taught to all years and at all levels, the curriculum was structured, but there did not appear to be consensus whether cognitive psychology should be foundational or an advanced topic. Understanding concepts was seen as crucial to developing transferable skills, described as, “more a mind-set than a collection of techniques that they’re going to need.” The frame of educators contrasted with the group of both practitioner-educators who deliver theory content first and take much more of a problem-solving approach to teaching, with an emphasis very much on application to practice. However, although the emphasis of the curriculum may be different, the delivery approach for both groups was similar, with all interviewees mentioning practical work and a project approach that complemented the theoretical approach. It was generally agreed that “project-based learning” supports the learning process and involving real-life clients enhances the student experience. As educator [E] Paul puts it, “Students enjoy courses where they design for real people.”

Educators do attempt to make their delivery as realistic as possible, using either real-life clients or realistic case studies. However, it was also agreed that whilst it is desirable, in practice it doesn’t always happen due to time and financial constraints, and sometimes educators must improvise. Variances were noted between the focus on educators and those who both practice and educate when discussing Agile methods. None of the educators mentioned UX in the context of Agile. However, those who both practice and teach are aware of the issues and take pains to include Agile methods within their curriculum or practice. Mila [UXA, Ed], in her practitioner role, spends “an amazing amount of my time doing teaching how to integrate UX into an Agile framework,” and Roger [UR, Ed] covers user stories as part of his curriculum delivery.

How Success Is Framed

To understand what practitioners and educators consider to be successful practice, all interviewees were asked to reflect on how they knew if a project was going well, or not, and the reasons for success or otherwise. All of the projects resulted in some kind of product, whether documentation, designs, or a software solution, and a number of different indicators of success emerged from the discussions. These can be separated into objective measures of success and a subjective assessment of success, which is personal to the individual and closely related to personal satisfaction. As an example, the identification of success may not be directly related to the end-product itself, but rather to the process which contributed to the product development.

Differences were noted between the roles of practitioners and educators. Whereas user researchers and UX architects commented on both objective and subjective success indicators, designers and educators associated success only with objective success indicators. Representatives from each of the groups of practitioners mentioned the success of products, particularly in the context of commercial success, and in the case of the designer group, this was particularly apparent, with all three interviewees referring to the success of the resulting products and the resulting external recognition. For designers, success is measured not only by the quality of the product but also the effect that a successful project has on the whole of the system development team, which is closely associated with good communication between UX and development teams and the interdisciplinary nature of the roles. User experience architects and user researchers offered more diverse definitions of success, and these included the actual effect on the product and the team. Subjective success indicators related to personal achievements and included problem-solving, exceeding the expectation of others, and providing efficient and effective solutions. There was also pride in the final deliverable, that is, objective success.

Although enthusiasm for the subject was evidenced across all roles, a passion for the subject was particularly evident amongst educators and user researchers. Both Antonina [E] and Helen [E] describe HCI as “beautiful,” with Helen adding, “That emphasis on the human and that humanistic set of philosophies and values… that’s what I get very excited about.” Tina [E] tells me that within her institution, there are several “people who feel passionately about it.” Clara [UR, Ed] tells me she “went to the British HCI in London one year as a student volunteer, and I was just hooked, absolutely hooked.” She uses the term “love” in the context of HCI nine times within the interview and is almost evangelical in her approach: “I love it! I just want to share it.” Kenneth [UR] echoes this, telling me, “I just love it.” Lucy [UR, Tr] describes HCI as “that dream of always combining computer science and psychology.” Terry, Antonina, and Helen all tell of how much they enjoy teaching the subject, with Terry and Antonina mentioning some “fun” aspects of teaching.

In summary, although some incongruences were noted between the groups on what is valued, there was much consensus. Valued skills were agreed to be communication, collaboration, problem-solving, creative thinking, and having a flexible and open approach. The methods adopted were appropriate to the role of practitioners; although, it was observed that mental methods were framed differently by UX architects and user researchers. UX architects found the elicitation of mental models useful to support and communicate the task analysis of different categories of end user, whereas user researchers used elicitation of mental models to understand and manage the expectations of the user. Differences were also observed in the design and delivery of the curriculum of educators and practitioner-educators, with the group including both delivering theory content first, taking more of a problem-solving approach to teaching, and integrating Agile into the curriculum. There were also differences between the roles in how success was framed. User researchers and UX architects commented on objective and subjective success indicators, whereas designers and educators associated success only with objective success indicators. User researchers and educators were the most passionate, and this shows in their interviews using words like “excited,” “love,” and “hooked.”

Concerns and Issues

Practitioner Concerns and Issues

Practitioner concerns and issues were not found to be associated with any particular role. The most significant concerns of practitioners were associated with the relative newness of the field and the speed with which it is developing. In the case of UX, this has resulted in the lack of a clear identity, no common vocabulary, nor standardized processes, which in our study reinforces the lack of a dominant design (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008). The lack of a clear identity caused particular concern to a user researcher: “UX can mean anything. It can mean the design; it can mean the people who gather the business requirements for an application or a project. It can mean any number of things. User experience is so vague.” The lack of consensus is not only restricted to job titles but extends to the terms used in practice, which can lead to operational and communication difficulties when different terms are used for the same artifact, such as a wireframe or a low fidelity prototype.

For example, Keith [UXA] described his design outputs: “UI specifications is what I call them. Most people would call them wireframes, but I think the specification part is a critical extra bit, or also they may call them annotated wireframes.” Talking about low fidelity prototypes, Keith [UXA] told me, “Everybody covers [low fidelity prototypes], in my experience. They don’t always call it that thing.” To clarify communication, Lucy [UR, Tr] told me she is “very keen on making sure there’s a shared understanding of terms,” and Mila [UXA, Ed] was sent to the Cooper Boot Camp with the express purpose of standardizing the terminology used by her team.

The rate of change of technology provides both opportunities and challenges to HCI professionals. For example, it is no longer necessary for teams or users to be physically co-located. Delia [D] told me: “I work 100% remotely—my team is distributed all over the place, a lot of the times we’re using some type of screen share and then white boarding things out that way.”

However, it was observed that the speed with which the technology changes can result in uncertainty, and unless one keeps abreast of developments, there is a risk that future advances in technology could invalidate current efforts. Larson works in the field of innovative technologies to advise and develop “stuff that hasn’t been developed before. So, at that point, the rules haven’t been written.”

Digby [UXA] observed that the field changes so fast that even training courses are not sufficiently responsive: “The problem I have with all the commercial stuff that I’ve looked at is it’s so far behind what’s actually happening in the field.” Josephine [UR, Ed] also recognized this issue: “I guess we need to educate to think beyond what currently is in interfaces and think about what could be.”

At times during the interviews, practitioners expressed frustration. This tended to be when they felt that the quality of their work was being compromised or when their efforts were not implemented. Often this was due to the lack of an influential voice, but it was also caused by internal policies, for example a marketing department restricting access to potential users or funding issues, such as removing resources from a project prior to its completion. Lack of time and budgetary constraints were mentioned several times, often associated with the constraints of Agile practice.

Another significant concern of those who are involved in practice is the lack of relevance of academic research to practice. The two participants most critical to the discipline described academic research as “out of touch” and “not relevant” in terms of practice; these individuals are both practitioners and educators in an academic setting and were placed in the category of practitioner-educators (both). One of these practitioners is also active with the User Experience Professionals Association (UXPA) and described his first attendance at CHI as uncomfortable “because it was so removed from anything that I work at or even what I teach my students.” There was also discussion of the difference between what is taught in the classroom and the actual practice. Josephine [UR, Ed] observed that the tools she has used in academia, such as Morae™, are useful and support the process, but they are also time consuming, and in the real world there are time constraints: “In reality would I use them again? Probably not because I’d probably still have to deliver my reports within three days.”

Other issues included tensions between the designer and developer groups, which were mentioned by designers, user experience architects, and to a lesser degree, user researchers. For example, Delia [D] felt that better communication early on would avoid the developers “writing the code, realizing that something is not right, and then having to go back and correct it.” Digby [UXA] mentioned a conflict with “the design person who was not really a digital person.” And Keith [UXA] refused to hand over high fidelity representations of interface design because “we don’t want your developers slicing it up.” Digby [UXA] expressed some frustration that developers do not do a good job of translating his designs into implementation.

Eight of the practitioners worked as contractors, and there was a definite sense that despite the experience and value that an individual can offer, or even the length of time in a role, they were outsiders. Helga [UXA], who works as an independent consultant, mentioned an unwillingness to collaborate, which she attributes to organizational politics. Helga said, “It is usually the team, it’s when people don’t want to work with the UX team or don’t cooperate well—it’s a matter of team politics and hierarchy.” Several of the independent interviewees felt less valued than a permanent employee.

Educator Concerns and Issues

The majority of barriers stemmed from shortcomings related to curriculum design, with poor integration of the individual modules within the program of study. Terry [E] stated, the field of HCI “lacks a coherence” across the modules of his program. Mila [UXA, Ed] stated that in her institution, “There is HCI 1 and HCI 2. You don’t have to take them in order which I think is a bit of a problem.” In Larson’s [SD, Ed] institution, they must teach HCI “without any implementation.” Educators also felt that they were not given sufficient time to cover the curriculum. Just as with practitioners, internal policies and funding issues were sources of frustration for educators, and these manifested themselves as barriers to delivering the curriculum.

In summary, the concerns and issues of the interviewed participants were not specific to particular roles. For practitioners, the most significant concerns related to the relative newness of the field and the speed with which it is developing. Other issues mentioned concerned compromises to practice due to time or financial constraints, tensions between research and practice as well as between systems development groups, and the problems of being an independent worker rather than an employee. For educators, internal policies and funding issues were also sources of frustration.

Discussion

The research question evaluated how the TFs of HCI practitioners and educators, and those who both practice and teach, varies from role to role due to their backgrounds, what is valued, and their concerns and issues. Regarding their backgrounds, results indicate that HCI practitioner and educator groups have their own TFs in terms of 1. users’ mental models, 2. HCI success, and 3. passion or enthusiasm for HCI. But they share TFs in terms of 1. communication skills, 2. collaboration, and 3. creativity. The incongruences between educators and practitioners reflect an unstable and maturing field. Those who are both practitioner-educators tend to align with educators’ or practitioners’ frames depending on their academic or commercial training, but they show awareness of shortfalls of each role.

We contend that our results indicate that the cognitive lens of TF applied to the standard technology lifecycle (Anderson & Tushman, 1990; Tushman & Rosenkopf, 2008) was a useful theoretical tool to study the phenomenon of HCI practice. We see it as our theoretical contribution that our study shows that HCI theory and practice can be conceptualized as a thing and technology that can be explored this way in a productive manner. A discussion of the main insights from the study about the TFs of what is valued, and related concerns and issues, follows.

Congruences and Incongruences in Valued Skills

We want to emphasize the overlap that we saw in the data between compulsory functional skills curriculum requirements and the naturally occurring opportunities to teach this within HCI. The attributes that were identified as desirable qualities for an HCI professional include communication skills, teamwork, problem-solving, creative thinking skills, and the ability to adopt a flexible and open approach. This list reflects those skills that have long been recognized as key employability skills, and they are in fact relevant to all professions. When a UK university course is validated, graduate attributes which closely resemble this list are embedded within the course design documentation, no matter the discipline, but that is not to say that the delivery of these subjects is seamless (Green et al., 2009). Academics already must prioritize which topics to include within the curriculum, and this is no doubt true of all disciplines. In some institutions, the academic specialist may feel that generic skills should not be delivered alongside disciplinary skills, and particularly when there is a modular delivery of the curriculum, graduate attributes are delivered as a standalone module (Bath et al., 2004; Yorke & Harvey, 2005). However, this need not be the case with the HCI curriculum. The core skills identified are integral to HCI practice, and it should be easy for both students and academics to see the relevance of activities which embed group work or communication skills that can easily be contextualized within the discipline (Jones, 2013).

Is it perhaps fair to say that the results represent only TF incongruence for specific skills and TF congruence for the recognition of teamwork? But then how does success and passion factor in? When the interviewees were asked what constituted success, educators offered only objective indicators of success, which doesn’t suggest that educators do not experience job satisfaction from their role. Educators exhibited a particular passion for the subject. The reason for differing definitions of success may have more to do with the academic environment in which success is very much measured by objective success indicators such as journal publications, citations, and retention and achievement figures. Designers also differed from user researchers and UX architects in their definitions of what constitutes success. The accounts of each designer referred only to objective success indicators associated with a product. However, user researchers and UX architects discussed objective success indicators associated with the product as well as a positive teamwork experience and subjective success indicators associated with personal efficacy.

Within education, as evidenced in the codes contained in the “delivering the curriculum” theme 2.3 (Appendix 3), education is delivered by both those who specialize solely in education and those who have another role in addition to being an academic, that is both. Some notable differences were observed in these two groups. In terms of curriculum delivery, educators reported that their HCI curriculum included cognitive psychology, interaction design, and evaluation techniques. The most apparent difference between educators’ curriculum and that of both practitioner-educators is the lack of commercial application; for example, those who are involved in both practice and education include Agile methodologies within their HCI curriculum. Similarly, although practitioner-educators place significant emphasis on tools and techniques that support practice, reference to these problem-solving approaches is not as apparent in the accounts of educators. For both educators and practitioner-educators, the use of real-life clients is recognized as good practice, and wherever possible it is embedded into the course delivery so that students are prepared for the uncertainties of the real world. What is lacking is the practical application of HCI methods reflecting the real-world problem-solving activities of practice. This is hardly surprising as the career path of the specialist educator suggests that they are unlikely to have had exposure to these tools and techniques, and the tools and techniques that are adopted by practitioners may not have been originally designed to support HCI activities. As a result, educators may well guide students in personas or software such as Axure to support the problem-solving process, but they may not think to include tools such as Excel or GoToMeeting®. This is an example of an incongruent TF, which may explain the mismatch between what is valued in education and what is valued in practice.

Concerns and Issues and the “Era of Ferment”

Our data suggests that the pragmatic desires of practitioners are still not being addressed by research-informed educators who are responsible for teaching HCI in the university. Practitioners see the educators as out of touch. Practice should be informed by academic research. Yet, the academic research also needs to be seen by practitioners as being relevant. Educators who focus on emerging technologies characterize the “era of ferment” (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008) and are accused their research-based teaching lacks relevance to practice.

The most significant concerns of practitioners were associated with the relative newness of the field and the speed with which it is developing. This manifested itself in the lack of a clear identity with no common vocabulary or standardized processes. In the context of the technology lifecycle (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008), it is particularly pertinent that the discipline of HCI is relatively young and, although there is no physical artifact, the state of the industry in relation to the processes and terminology bears some resemblance to the “era of ferment,” with variation between practices and what practitioners and educators value. The ambiguity and lack of agreement regarding the terminology has resulted in the lack of a common vocabulary, and the variety of tools and techniques currently used reflects both the diversity of practice and the adaptive nature of a fast-moving field.

Educators’ issues were for the main part well known and common to educational settings rather than specific to the field of HCI, and practitioners mentioned a number of issues, many of which would apply to any industry, which were not explored in this study. The issues most relevant to this discussion are the tension between practice and research and the lack of a dominant collective TF that manifests as a lack of consensus in terminology and methods, which is seen as being particularly damaging to the profession.

The lack of a dominant design is apparent in the criticisms raised by practitioners that current academic research bears little relationship to practice, and that the direction of the research places too much emphasis on computer science. Kaplan and Tripsas (2008) suggest that the institutions can provide an arena for producers, users, and other institutions to come to a common understanding and thereby stabilize divergent frames. Whilst events such as CHI and UXPA conferences go some way to meeting a focused set of institutional arenas (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008), the gap between the academic and practitioners’ research is still wide. This gap is nothing new. For example, Gulliksen (2004) discusses established research participatory design methods and its lack of adoption into practice. However, compared to the many previous studies of a variety of aspects of HCI and UX/usability professionals’ practices (Inal et al., 2020), our study gives a holistic, higher-level, and dynamic view that reflects on design changes in graduate curriculum and executive HCI curricula.

Although it could be argued that HCI as a field is unlikely to ever leave the “era of ferment” and fully stabilize on a “dominant design” due to the rapidly changing nature of technological advances and social and political forces, TF allows us to see convergence and divergence in this field across different types and communities of HCI practitioners and educators. This research shows how there are clear areas of convergence within and across the groups studied and how there are many more areas still “fermenting.” The changing character of HCI as a young field of knowledge and practice has already been documented and discussed by other authors, and our study also contributes to this body of knowledge (Bødker, 2015; Frauenberger, 2019).

Contribution to Research on HCI Education and Technological Frames

This study complements previous studies into HCI education such as the SIGCHI Education project (Churchill et al., 2013a) by providing four contributions to knowledge. First, this study provides the additional perspective of those who are involved in both education and practice. Although Churchill and colleagues (2013a) surveyed students as well as practitioners and educators, they did not incorporate the role of both practitioner-educator in their findings.

Second, although there is some overlap in the areas of investigation, and some commonality in the findings, our argument also differs from the SIGCHI project (Churchill et al., 2013a) in that its emphasis is on the different TFs of the HCI practitioners and educators rather than on the position of HCI education and the requirements of the curriculum. Our study identifies differences between these roles and sub-roles.

Third, the emphasis on practitioners differs in this study. Churchill et al. (2013a) interviewed hiring managers, concentrating on five large US tech companies. In contrast, the majority of practitioners in this sample are from non-US small-to-medium-sized enterprises, and a range of roles is represented, thereby providing an alternative view of the HCI commercial landscape. Compared to the SIGCHI project, our emphasis may thus be much more relevant for HCI practitioners and educators in the many smaller countries of the world.

Finally, previous studies have adopted the concept of TFs to explain attitudes towards IT such as user acceptance, usability, and usefulness of systems (Abdelnour-Nocera et al., 2007; Karsten & Laine, 2007; Shaw et al., 1997) or the integration of IT systems (Davidson, 2002, 2006; Lin & Silva, 2005; Olesen, 2014; Orlikowski & Gash, 1994). Our study, in contrast, has adapted TF to consider the HCI educators and practitioners by probing their implicit understanding, assumptions, and expectations, and then positioning these roles and sub-roles within the context of the technology lifecycle (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008) to help understand the “era of ferment” in HCI as a changing field of knowledge and practice.

Limitations

To help interpret the contribution of this paper, we provide three limitations. First, we sampled data about 10 different and fragmented sub-roles across 21 participants, so it may be argued that saturation from data collection was never fully reached in our study. However, by saturation we mean stopping data collection and analysis when there is no contribution of new and unique findings to the overall state of knowledge. Note that in our case, if we continued additional purposeful sampling to more highly saturate differing roles, we might have found that HCI curricula should represent a wider subset of skills needed for real-world work. Such a relation between HCI knowledge and other knowledge is a topic for future research. Second, we focused on practice and not on academic research. Thus, our interviews with academic educators were underpinned by an interest in their perception of HCI and its applicability to curricula and professional practice. However, we acknowledge that getting insights into perceptions of those with a prominent HCI academic research role would be beneficial in getting a broader understanding of TFs in HCI. The latter is the subject of a wider and ongoing program of research which will be eventually published. Third, in this study we aimed to define different perspectives identified between the educator and both practitioner-educator groups. It makes sense that these groups would think differently about the field and thus teach differently as well. However, we did not study to what degree these differences overlap within teaching context. In principle, it could be the case that the different perspective of the practitioner-educator group was due to teaching in an applied or within-company context versus the educator group, who may have been more likely to teach in an academic setting. Most of our participants (educators and practitioner-educator) taught in academic settings, with only two teaching in industry settings. Therefore, while their views were captured and analyzed, we did not study training or mentor roles in industry in depth. For future studies, however, it would be very helpful to recognize and explore the possibility to see how the analysis might change if the comparison were shifted from educator versus practitioner-educator to academic setting versus non-academic setting.

Conclusion

In this study, we interviewed HCI practitioners and educators about how they framed HCI. We found that their background is increasingly diverse and for many it is not the first career choice. The data analysis clearly shows a contrast between HCI practitioners and educators in terms of users’ mental models, HCI success, and passion or enthusiasm for HCI as well as convergence on the value of communication skills, collaboration, and creativity. Interesting differences found include those between specialist educators and non-specialist practitioner-educators with the curriculum of the latter exhibiting far more commercial application and shared perceptions more aligned with practitioners’ TF. Differences were also found within the TF of practitioners between the role of designer and other roles, which is restricted to early in the project lifecycle and appears to be more insular than the other roles. The TF of educators differs from most of the other roles in terms of success indicators.

Overall, key findings are the lack of a dominant collective TF, which was discussed in the context of the technology lifecycle, different views on specific HCI skills and concepts (such as elicitation of mental models), and the gap between research and practice, in which institutional actors also have a role to play to resolve these issues. However, the TFs of the HCI practitioners and educators also shows points of congruence on valuing skills non-specific to HCI such as communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and creativity.

Tips for User Experience Practitioners

Based on this study, we make the following recommendations to usability and user experience practitioners:

- If you are a UX professional who designs training and teaching programs for students or professionals, include in the curriculum an exercise about reflecting on the evolution and change of major concepts driving HCI theory and their relevance, or lack of, to current UX practice. This can, for example, be done by discussing HCI waves or, as we suggest, technology lifecycles.

- If you are a senior UX manager, pay attention to incongruences in terms of mental models, success, and passion for HCI theory between those professionals who have done mostly teaching and those who have done mostly design and evaluation. Your UX team may be more inhomogeneous than expected on these key parameters, which may require additional training and facilitation.

- As an early career UX professional, make sure to develop teamwork skills including communication, collaboration, and creativity. While these might seem like non-specialist skills, our study demonstrates how critical they are for success and career mobility in the HCI field.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all the participants who agreed to give their valuable time to contribute to the understanding HCI as a field of knowledge and practice.

References

Abdelnour Nocera, J., Clemmensen, T., Joshi, A., Liu, Z., Biljon, J. van, Qin, X., Gasparini, I., & Parra-Agudelo, L. (2021). Geopolitical Issues in Human Computer Interaction. IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85607-6_73

Abdelnour-Nocera, J., Dunckley, L., & Sharp, H. (2007). An approach to the evaluation of usefulness as a social construct using technological frames. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 22(1–2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447310709336959

Anderson, P., & Tushman, M. L. (1990). Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: A cyclical model of technological change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 604–633. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393511

Bath, D., Smith, C., Stein, S., & Swann, R. (2004). Beyond mapping and embedding graduate attributes: Bringing together quality assurance and action learning to create a validated and living curriculum. Higher Education Research & Development, 23(3), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436042000235427

BCS. (2018). BCS Foundation Certificate in User Experience Syllabus. https://www.bcs.org/media/1834/ux-foundation-syllabus.pdf

Benyon, D. (2014). Designing interactive systems: A comprehensive guide to HCI, UX and interaction design (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Bijker, W. E. (1987). The social construction of Bakelite: Toward a theory of invention. In The social construction of technological systems (pp. 159–187). MIT Press.

Bijker, W. E. (1995). Of bicycles, bakelites, and bulbs: Toward a theory of sociotechnical change. MIT Press.

Bødker, S. (2015). Third-wave HCI, 10 years later—Participation and sharing. Interactions, 22(5), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/2804405

Boivie, I., Gulliksen, J., & Göransson, B. (2006). The lonesome cowboy: A study of the usability designer role in systems development. Interacting with Computers, 18(4), 601–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2005.10.003

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Britannica (2021). Technology. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/technology

Carroll, J. M. (2010). Conceptualizing a possible discipline of human-computer interaction. Interacting with Computers, 22(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2009.11.008

Churchill, E. F., Bowser, A., & Preece, J. (2013a). Report of 2012 SIGCHI Education Activities. https://new.sigchi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Report-of-2012-Education-Activities.pdf

Churchill, E. F., Bowser, A., & Preece, J. (2013b). Teaching and learning human-computer interaction: Past, present, and future. Interactions, 20(2), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1145/2427076.2427086

Clemmensen, T. (2005). Community knowledge in an emerging online professional community: The case of Sigchi.dk. Knowledge and Process Management, 12(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.206

Clemmensen, T., Hertzum, M., Yang, J., & Chen, Y. (2013). Do usability professionals think about user experience in the same way as users and developers do? IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 461–478. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-40480-1_31

Davidson, E. (2002). Technology frames and framing: A socio-cognitive investigation of requirements determination. MIS Quarterly, 26(4), 329–358. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4132312

Davidson, E. (2006). A technological frames perspective on information technology and organizational change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 42(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886305285126

Douglas, S., Tremaine, M., Leventhal, L., Wills, C. E., & Manaris, B. (2002). Incorporating human-computer interaction into the undergraduate computer science curriculum. ACM SIGCSE Bulletin, 34, 211–212. https://doi.org/10.1145/563340.563419