Abstract

While usability evaluation and usability testing has become an important tool in artifact assessment, little is known about what happens to usability data as it moves from usability session to usability report. In this ethnographic case study, I investigate the variations in the language used by usability participants in user-based usability testing sessions as compared to the language used by novice usability testers in their oral reports of that usability testing session. In these comparative discourse analyses, I assess the consistency and continuity of the usability testing data within the purview of the individual testers conducting “do-it-yourself” usability testing. This case study of a limited population suggests that findings in oral usability reports may or may not be substantiated in the evaluations themselves, that explicit or latent biases may affect the presentation of the findings in the report, and that broader investigations, both in terms of populations and methodologies, are warranted.

Practitioner’s Take Away

The following are key points from this study:

- User-based usability testing creates a lot of data. Only about one fourth of the issues mentioned by the participants in this study were reiterated by the evaluator in the oral reports.

- Most reported data in this study did stem from the usability testing. About 84% of the findings in the oral reports had some referent in usability testing.

- In this study, more than half of the findings in the reports are accurate reflections of the usability testing.

- About 30% of the findings in the oral reports inaccurately reflect the usability testing in this study.

- “Sound bite” data were likely to be more accurate reflections of usability testing than interpreted data in this study.

- A substantial portion of the reported findings in this study (about 15%) has no basis in the usability testing.

- In this study, between the findings that had no basis in usability testing and the inaccurate findings from the usability testing, 45% of the findings presented in the oral reports were not representative of the usability testing.

- In this study, the evaluators who conducted the “do-it-yourself” testing never presented a finding to the group that ran counter to an opinion or claim offered by the evaluator prior to the usability test, although they had ample opportunities to do so.

- More research into conscious and unconscious evaluator biases and evaluator methods of interpretation are needed to establish best practices for more highly accurate usability testing analysis, particularly for do-it-yourself usability testing.

Introduction

This descriptive case study compares the discursive differences between the language used by end-users during a think-aloud protocol to the language used by the evaluators of those sessions in their oral follow-up reports. Previous studies have shown that multiple evaluators observing the same usability session or multiple evaluators conducting expert or heuristic evaluations on a static artifact will likely detect widely varying problems and develop potentially dissimilar recommendations (Hertzum & Jacobsen, 2001; Jacobsen, Hertzum, & John, 1998; Molich, Ede, Kassgaard, & Karyukin, 2004; Molich, Jeffries, & Dumas, 2007). However, no previous study has investigated the internal consistency of the problems revealed in a user-based usability testing (UT) session as compared to the problems and recommendations described in the subsequent usability report. In other words, no study has explored whether the problems described in a usability report were, indeed, the same problems described by end-user participants in the UT session itself.

To do this, I use discourse analysis techniques and compare the language used by the end-users in the testing sessions to the language used in the evaluators’ oral reports. This case study reveals what is included, misappropriated, and omitted entirely in the information’s migration from usability testing session to report. By looking at the language used in these two different parts of the usability testing process, we can potentially determine how issues such as interpretation and bias can affect how usability findings are or are not reported. Language variance between the UT session and the report may indicate that more research may be needed on how evaluators, particularly novice evaluators, assess and assimilate their findings.

Site of Investigation

In order to determine the fidelity of the information revealed in usability evaluations as compared to information presented in usability reports, I observed a group of designers who overtly claimed to follow the principles of user-centered design by conducting UT early and often throughout their design process. This group consisted of approximately 18 relatively novice designers who were charged with redesigning documents for the United States Postal Service (USPS). These designers were current graphic and interaction design graduate students; however, all of the work they completed on this project was entirely extracurricular to their degree program. While they did not receive course credit for their work, they were paid for their work. Working on the project was highly desirable, and it was extremely competitive to be selected to the team. During the course of their degree program, all of the student designers would eventually take two courses on human-centered design, usability testing, and user experience, though at no time had all the student designers taken both of the courses. All of the students worked 20 hours each week for the USPS, while a project manager and an assistant project manager worked full-time on the project.

In the usability evaluations in this study, the document under review was a 40-page document aimed at helping people learn about and take advantage of the services offered by the USPS. These designers conducted what Krug (2010) calls “do-it-yourself” usability testing in that the designers conducted their own usability testing and that the evaluations were not outsourced to a separate group dedicated solely to usability evaluation. Although some may advocate to have a separate group of evaluators who are not involved in the design, the combination of usability evaluation and some other task, such as technical communication or design, is not a rarity and can improve design (Krug, 2010; Redish, 2010).

There were five rounds of formative testing, with each round testing between 6 and 15 usability participants. The sessions in this study came from the third round of usability testing in which six participants were tested. The three sessions evaluated in this discursive analysis represent the three viable sessions in which all necessary secondary consent was received. Approximately six team members developed a testing plan for each round of evaluation, though only one team member (the project manager) was on every team that developed the testing plan for each round of evaluation. The stated goal for this particular round of evaluation was to determine the degree of success in the navigation of the document.

The testing plan consisted of four major parts. First, the usability participant was asked pre-test questions related to his or her familiarity with the postal service and mailing in general. Second, the usability participant was asked to read aloud a scenario related to mailing. The participant, after a brief description of the think-aloud protocol and a short example of thinking aloud by the moderator, was asked to think aloud while he or she used the document to complete the task. In addition to thinking aloud, the participant was given a set of red and green stickers and was asked to place a green sticker next to anything in the document the participant “liked” and a red sticker next to anything the participant “disliked.” Though this method was never overtly named, in practice it seemed akin to “plus-minus testing” in which “members of a target audience are asked to read a document and flag their positive and negative reading experiences” (de Jong & Schellens, 2000, p. 160).

The participants completed two major scenarios and two minor scenarios in these sessions. Upon completion of each of the scenarios, the evaluator asked the participant a series of post-task questions. Finally, at the end of all the scenarios, the evaluator asked the participant a series of pre-determined, post-test questions related to the navigation of the document as well as questions related to comments the participant made throughout the evaluation session. These sessions took about 45 minutes to one hour to complete.

Members of the design team recruited volunteer usability participants, who were usually friends, family members, or volunteers recruited from signs on campus. The usability participant’s session was conducted by someone other than the person who recruited him or her to the study. The sessions took place either in the design team’s studio or at the participant’s residence.

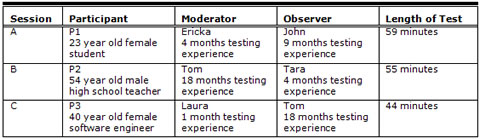

Each session was conducted by two team members. One member of the pair was the moderator who would ask questions, gather the informed consent, prod for more information, and answer the participant’s questions during the evaluation. The second member of the pair generally ran the video camera and took notes as to what the participant did during the session. These testers had varying degrees of experience in conducting usability tests, though none could be called “expert.” Oftentimes, the team member with less experience moderated the sessions to gain experience. The team member with the most experience had about three years worth of experience, while some team members had yet to conduct a session. The evaluators of the UT sessions in this study had little to moderate experience moderating or observing usability tests. The setup of the three sessions I evaluated using discourse analysis is shown in Table 1.

I obtained approval from my institution’s institutional review board (IRB) for my study, and all of the designers gave written informed consent that permitted me to record the oral reports given in the large group meetings and to include their conversations from the usability sessions in my research. The usability teams received approval from the same IRB for their evaluation studies and gave their usability participants written informed consent that permitted the teams to record the usability participant. Part of that consent indicated to the usability participant that the video collected could be used by other researchers affiliated with the institution as long as the established privacy standards stayed in place. Given that the design team and I were affiliated with the same institution, the IRB approved my use of the usability session video for this research without obtaining secondary consent from the usability session participant. However, to maintain the established privacy, the UT participants were referred to as P1, P2, and P3; the evaluators were referred to by fictitious names.

Table 1. Usability Testing Session Participants and Evaluators

In the two weeks after the evaluation, the entire design team met to discuss developments and progress made on the document. One standard portion of the meeting was oral reports on the usability sessions. These informal oral reports were led by the moderator of the session. In these meetings, each usability session was covered in 2-5 minutes, though occasionally the oral report would last longer. Immediately following the oral reports, the designers would then discuss what changes to the document were necessary in light of the findings from the testing sessions. Because these sessions were conducted by non-consistent pairs of evaluators, there was no synthesis of results across the UT sessions prior to the meeting.

Upon completion of the testing session and prior to the group meeting, each pair of evaluators was supposed to write a report highlighting the findings of the usability session. However, the extent to which these reports were actually written is unknown. In the months of observations, it appeared that a handful of the evaluators always had a written report, while the majority of the evaluators never had a written report. During a lull in one meeting in which the project manager had to step away to take a phone call, Lily, a new team member, asked Tom, one of the most experienced members of the team, if there was an example of a usability report that they could use as a template. Tom said, “You probably won’t have time to write the report. I mean, if you do, great, but you’re gonna be busy with lots of other things.” When Lily asked who should get the findings from the usability sessions, Tom said, “All of us. You’ve got to make sure when you present to the group you get the most important info ‘cause if you don’t tell us about it, we’ll never know.” Over the course of the observation, there was never a request by anyone on the team to look back at the written reports; however, on many occasions, the moderators of previous usability sessions were asked point-blank by other members of the team about issues from tests weeks earlier, and the group relied on the moderator’s memory of the issue.

Method

In order to compare the language of the end-user UT participants to the language of the evaluator’s reports, I conducted a comparative discourse analysis on the transcripts that were created from the video recordings of the three usability tests and from the audio recording of the group meeting in which the oral usability reports of all three sessions were discussed. The transcripts were segmented first into conversational turns and then into clauses. Conversational turns begin “when one speaker starts to speak, and ends when he or she stops speaking” (Johnstone, 2002, p. 73). Clauses are considered “the smallest unit of language that makes a claim” and such granularity is useful in this analysis as the speakers often presented multiple ideas per turn (Geisler, 2004, p. 32). Two raters with significant experience in usability testing and heuristic evaluation were asked to compare the transcript from each usability test to the transcript of the oral usability reports; additionally, the raters were allowed to refer to the audio and video recordings. It took each rater about 1.25 to 1.55 times longer than the recording time to assess the transcripts. The raters typically read the short oral report first and listed the findings from the report. Then they read the transcripts from the UT and listed the findings from the session. They then read through the transcripts an additional time and referred to the recordings themselves, if they wished (each rater referred to a video recording of the usability test twice, but neither referred to the audio recordings of the oral reports). In this comparison, the raters were asked to identify items that were mentioned in both the usability test and in the oral report, items that were mentioned in the usability test but not in the oral report, and items that were mentioned in the oral report but were not mentioned in the usability test. In a way, this classification of usability findings is similar to Gray and Salzman’s (1998) hit, miss, false alarm, and correct rejection taxonomy; however, in this current study, the goal is not to determine the true accuracy of the reported finding (which, according to Gray and Salzman, would be nearly impossible to ascertain), but the accuracy of the reported finding as compared to the utterances of the usability testing participants. After an initial training period, the two raters assessed the data individually. Ultimately, across all three categories, the raters had a percent agreement of 85% and a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.73, which, according to Landis and Koch (1977), demonstrates good agreement.

Additionally, the raters were asked to determine if any of the issues mentioned in the oral report but not mentioned by the usability participant could be reasonably assumed by the actions of the usability participant in the think-aloud usability test. For example, in one situation the usability moderator mentioned in the oral report that the usability participant “struggled with navigation.” Though the usability participant never mentioned anything related to navigation or being lost, the participant spent several minutes flipping through the document, reading through the pages, and ultimately making a decision about the task using information from a non-ideal page. Though the participant never explicitly mentioned the navigation problems, “struggling with navigation” was a reasonable assumption given the behavior of the participant. Information that was not overtly stated and only implied was a severely limited data set as most of the issues were ultimately alluded to during the think-aloud protocol by the usability participants themselves or through the questions asked by the moderator during the post-task follow-up. In this limited set, the raters had a percent agreement of 80% and a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.65.

Results

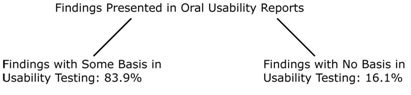

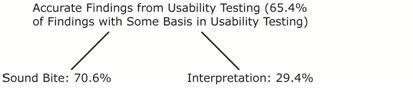

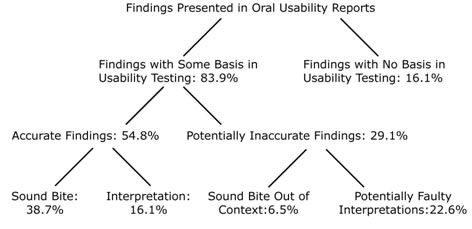

During the three oral usability reports, which took on average about four minutes, 31 total usability findings were presented to the large group. Team A (Ericka and John, who interviewed P1) presented 11 findings. Team B (Tom and Tara, who interviewed P2) presented 13 findings. Team C (Laura and Tom, who interviewed P3) presented 7 findings. Of these 31 findings, 26 findings (83.9% of the total findings) could be found to have some basis (though not always an accurate basis) in the respective UT session either through the language used by the usability participant or through reasonable assumptions from the actions described in the think aloud. The remaining findings presented in the usability reports (16.1% of the total findings) had no discernible basis in the language of the end-user participants in the usability sessions. The breakdown of the findings presented in the oral reports is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Breakdown of source of findings in oral usability reports

Accurate Findings Stemming from Usability Sessions

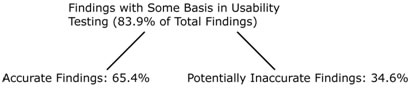

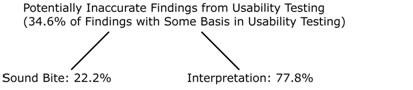

Of the findings mentioned in the oral report that had some basis in UT, 65.4% seemingly accurately conveyed the intent of the statement made in the evaluation. Though the finding in the oral report did not have to be identical to the finding in the study in order to be considered accurate, the finding had to clearly represent the same notion that was conveyed in the test. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of accurate and potentially inaccurate findings in the findings with some basis in usability testing.

Figure 2. Breakdown of findings with some basis in usability testing

Accurate “Sound Bite” Findings

Of the seemingly accurate findings, 70.6% were derived from singular, discrete clauses in the UT that I call “sound bite” findings, as opposed to interpreted findings. Sound bite findings are based on a small portion of a conversation and are often verbatim repetitions of the words used in the usability testing by the testing participants.

As an example of a sound bite finding, in a post-task questioning, Tom asked P2 if there was “anything in particular that caused [P2] uncertainty while [he was] completing the task.” After initially denying that there was anything, P2 said, “Well, that one thing said ‘mailpiece.’ I don’t [know] what that meant. Sounds like ‘hairpiece.’” In the subsequent oral report, Tom said, “He also mentioned that he didn’t like the term ‘mailpiece.’” Clearly, Tom’s statement stemmed directly from P2’s statements during the think aloud study. Additionally, Ericka stated in her oral report that P1 “said straight up that she skipped [a section of the document] because it reminded her of a textbook.” This clearly referenced an exchange in the usability study itself:

P1: Yeah, I didn’t read this page but I hate it.

Ericka: Why?

P1: It reminds me of my 10th grade history textbook.

Ericka: In what way?

P1: Just a lot of text, ya know.

Figure 3 shows the breakdown of sound bite and interpretation findings in the accurate findings from usability testing.

Figure 3. Breakdown of accurate findings from usability testing

Accurate Interpretation Findings

The remaining accurate findings (29.4% of the accurate findings) were not derived from a singular sound bite, but were accurate interpretations from the UT. For example John, in the report of P1’s test, said, “Just to clarify, she only used the table of contents. She didn’t read from front to end, and that jumping back and forth might have hurt her.” Though P1 never said that she only used the table of contents (and not the headings) and she never said that she was “jumping back and forth,” the actions and behaviors revealed in the think aloud show this to be an accurate account of what occurred. Indeed, in one task, P1 flipped to the table of contents five times and spent over 10 minutes attempting to complete a task, but in that time she never looked at the particular page that had the information required to complete the task.

Similarly, Tom said of P3, “She seemed to have a little trouble navigating the information at the beginning.” Again, P3 never said that she had trouble navigating the information, but her actions, which involved her flipping through pages of the book and then, after acknowledging “getting frustrated” (though she never explicitly said at what), arbitrarily picking a response, seemed to appropriately indicate that she did, indeed, have “trouble navigating the information.”

Potentially Inaccurate Findings Stemming from Usability Sessions

Of the findings mentioned in the oral report that had some basis in the UT, 34.6% of the findings seemingly inaccurately conveyed the intent of the statement made in the evaluation. A breakdown of the types of inaccurate findings is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Breakdown of potentially inaccurate findings from usability testing

Potentially Inaccurate Sound Bite Findings

Of these inaccurate findings, 22.2% dealt with a singular, discrete finding taken out of context. For example, in the oral report about P2’s test, Tom said, “He liked the chart on the extra services page.” Technically, this is correct, as P2 said in his usability test shortly after seeing the chart, “I really like this chart.” However, P2 could not use the chart to find an appropriate solution to the task. Additionally, though P2 said that he “really like[d]” the chart upon first blush, he later recanted that statement with, “Wow, it looks good, but now that I’m trying to, you know [make a decision with it], it’s kinda confusing.” Tom asked, “What’s confusing about it?” P2 said, “I guess it’s all these terms. I don’t know what they mean.” Therefore, although P2 did initially say that he liked the chart, Tom’s presentation of that statement is not entirely accurate.

In another example, Ericka said of P1, “she was a little confused by [the icons].” And, indeed, P1 did say in her usability test, “What are these supposed to be?” However, less than a minute later, P1 said, “Oh, these are pictures of the shapes of things I could be mailing. So I can use Delivery Confirmation if I have a box, or a tube, or a big letter, but I can’t use it if I have only a little letter.” She then completed the task using the chart with the icons. Therefore, although P1 did initially show some trepidation with the icons, through her use of the document she learned how the icons were supposed to be used. However, Ericka seized upon a singular statement of confusion and used that as a finding, rather than placing it within the context of the study.

Potentially Inaccurate Interpretation Findings

The remaining inaccurate findings that had some basis in the usability study dealt with findings that seemed to potentially have problems in their interpretation. For example, Tom, in his report of the session with P2 said, “He didn’t like the font on the measuring pages.” Indeed, P2 did discuss the font on the pages that dealt with measuring mailpieces, but his comments did not necessarily indicate that he “didn’t like” the font (which P2 refers to as a “script”). The exchange went as follows:

P2: Huh, that’s an interesting script.

Tom: Where?

P2: Here. I don’t think I’ve ever seen that before, and I read a lot. Okay, here we go. This here looks like it’s discussing how to pack…

While P2 made the comments that the “script” was “interesting” and that he hadn’t seen it before, he didn’t indicate, either through his language or his intonation, that he did not like the font. Tom did not further question P2 to determine if his comments meant that P2 truly did not like the font or the comments could be taken at face value. Therefore, the assumption that P2 “didn’t like the font” was perhaps faulty.

Similarly, in a discussion of a chart, Laura said of P3, “She liked the chart.” P3 did mention the chart in her usability session, but her comments were more equivocal than what Laura presented. In her session, P3 said, “There’s something about this chart…there’s all the stuff I need, but…wait I think I’m on the wrong page.” Laura did not follow up with what P3 meant by “there’s something about this chart.” From her language choices, it was not clear whether the “something” was a positive attribute or a negative attribute. Therefore the interpretation that Laura made that P3 “liked the chart” may or may not be appropriate.

Findings with No Substantiation in Usability Sessions

In addition to the findings that potentially had some basis in usability sessions, 16.1% of the findings reported in the oral reports seemingly had no basis in the usability sessions. For example, Tom, in discussing what P2 said of a service chart, said, “…he really liked the chart. Said that it made him feel confident in the document.” However, at no time during P2’s session did he ever mention the word “confident.” Further, in the discussion of the particular chart, P2 indicated that this particular chart was “odd” and “misleading.” Therefore, it appears that Tom’s statements in the oral report that P2 felt confidence with the chart have no grounding in the usability study.

In another example, Ericka said that P1 “…didn’t like the hand drawn images, but liked the line art.” In this example, the first clause regarding the hand drawn images is an accurate sound bite because in her study P1 said, “the icons that were drawn [by hand] didn’t help [me feel like this was a document for adults and not for kids]. Yeah, these ones [indicating the hand drawn icons], not so much.” However, the second clause referencing the line art has no basis in the usability study. At no point in the study did P1 indicate that she “liked” any of the images that were created using line art. The only alternative to the hand drawn images given by P1 was photographs, in “I think maybe photos are the way to go.” Therefore, the indication that P1 liked line art was unsubstantiated in the usability study itself.

Findings from Usability Sessions Not Mentioned in Oral Reports

Not surprisingly, many potential findings in the usability studies were not mentioned in the brief oral reports. The potential findings were determined by the two raters in their list of items that were mentioned in the study but not mentioned in the report. The two raters had a 96.8% agreement on the list of items, with one rater identifying one finding that the other rater did not, which was not included in the list. According to the raters, the three tests averaged 33.3 discrete findings per session, with the high being 37 findings from Team A and the low being 28 findings from Team C. (Though an issue might have been mentioned by a UT participant several times, it was only counted once as a finding). During the oral reports, 10.3 findings were reported on average, with the high being 13 findings from Team B and the low being 7 findings from Team C. After removing the findings reported in the oral reports that had no basis in the usability test, approximately 26% of the total findings from the usability sessions were reported in oral reports.

Figure 5. Summary of usability findings presented in oral usability reports

In this case study, it appears that the group used findings from usability testing in highly particular ways (see Figure 5). Ultimately, it appears that three results emerged:

- About one fourth of the potential findings from the usability tests were mentioned in the oral reports.

- The majority of the findings presented in the oral reports (83.9%) had some basis in usability testing.

- A substantial portion of the findings presented in the oral reports either were inaccurately transferred from the test to the report or had no basis in the test, meaning that in terms of the overall number of findings presented in the oral reports, only 54.8% of the findings could be deemed as accurate from the usability evaluation.

Discussion

This group partook in do-it-yourself usability testing in that the designers who developed the document for the postal service were the same people who conducted the usability testing itself. Although every usability test was video recorded, to the best of my knowledge, none of the videos were reviewed by any member of the group (including the evaluators) after the test. Therefore, the only people who had access to the information revealed during the test were the two evaluators who moderated and observed the test.

These evaluators were, thus, placed in a broker of knowledge position—certainly a position of potential power. The evaluators of the usability tests determined what information from the tests was presented to the group and what information was omitted. From this gatekeeper position, the evaluators had the capacity to influence the outcome of the document by restricting, altering, or overemphasizing information gathered from UT in their oral reports. I do not mean to suggest that alterations to the findings were done maliciously or even consciously by the reporting evaluators. Nonetheless, the findings in the oral reports often had changed from or had no basis in the usability reports. In what follows, I explore possible explanations as to why the findings presented in the oral reports did not always accurately represent what occurred in the UT.

Confirmation Bias in Oral Reports

Either intentionally or unintentionally, the evaluators appeared to seek out confirmation for issues that they had previously identified. For example, in his oral report on P2’s session, Tom mentioned on three separate occasions that P2 “liked” a particular chart. Indeed, P2 did say at one point in the study, “I love this chart,” but P2 never mentioned that particular chart again. At the large group meeting immediately prior to the one with these oral reports, a fellow team member questioned Tom as to whether this particular chart was intuitive to the needs of the user. Tom’s repetitive statements that P2 “liked” this chart may be residual arguments for the prior discussion or an attempt to save face in front of the group. While the information was correctly transferred from the usability study, the selection of that finding and the repeated mentioning of that finding was perhaps misplaced.

In another instance, Tom mentioned that P2 did not like the font on the measuring pages. As discussed previously, P2 never outright said that he did not like the font, but instead said that he found it “interesting” and that he had “never seen it before.” Tom parlayed that into a statement that P2 “didn’t like the font on the measuring pages,” which may or may not be accurate. However, the reported finding that P2 didn’t like the font supports a claim that Tom had made in many prior meetings that the font on the measuring pages was “inappropriate” and “at least needs its leading opened up.” By interpreting the finding as negative rather than a neutral statement, Tom lends credence to his ongoing argument to change the font. I am not suggesting that Tom intentionally misread the data to support his personal argument. However, it may be that Tom perhaps unintentionally appropriated the equivocal statement from P2 to support an issue that clearly meant quite a lot to him.

Additionally, Ericka mentioned that P1 “wanted page numbers at the bottom,” which was an accurately reported finding, but one that also supported Ericka’s ongoing claim that the top of the pages were too cluttered to also have page numbers. Further, Laura mentioned that P3 had “a little bit of trouble navigating the information at the beginning” possibly because the “TOC …was four pages in.” Again, this was accurate from the usability study, but it also supported a concern that Laura had mentioned in a previous meeting that the table of contents wasn’t in the proper spot for quick skimming and scanning.

Ultimately, of the findings presented in the oral reports that had some basis (accurate or not) in the usability sessions, approximately one third of the findings were in support of an issue that the evaluator had previously mentioned in the group meetings. Therefore, it may be that instead of looking neutrally for global concerns throughout the testing, the evaluators were keeping a keen ear open during the evaluations for statements and actions that supported their own beliefs.

This notion of confirmation and evaluator bias is nothing new; indeed, in 1620 in the Novum Organan, Francis Bacon said, “The human understanding, once it has adopted opinions, either because they were already accepted and believed, or because it likes them, draws everything else to support and agree with them” (1994, p. 57). According to Bacon, and countless others since the 17th century, it is in our nature to seek support for our beliefs and our opinions, rather than try to identify notions that contradict our own. Therefore, these evaluators seem to have similar issues to those described by Jacobsen, Hertzem, and John: “evaluators may be biased toward the problems they originally detected themselves” (1998, p. 1338). These evaluators sometimes accurately represented the findings to support their cause and other times evaluators seemingly “massaged” the findings to match their causes. For example, Tom appears to massage his findings. Tom’s clinging to P2’s statement that P2 liked a chart, despite the singular mention by P2, or Tom’s reporting that P2 didn’t like a font, despite P2 saying that it was “interesting” suggests that in some way Tom is looking for data within the scope of the evaluation sessions that support his ongoing claims.

Conversely, Laura’s report that P3 had trouble with navigation due to the location of the table of contents, and Ericka’s report of P1’s dislike of the page numbers at the top of the page did, in fact, support their ongoing claims, but also accurately conveyed the findings from the usability session. Laura and Ericka’s findings were subsequently retested and, eventually, changes were made to the document to reflect their findings from their usability sessions and, ultimately, the claims they made prior to the evaluation sessions. While it may be that the evaluators were trolling for findings during UT sessions that they could employ for their own causes, it may also be that they were advocates for these issues. Though there was no separately delineated design team and usability team, the design team did have specialists: chart specialists, organization and navigation specialists, icon and image specialists, writing specialists, printing specialists, color specialists, and many others. (Though, despite their specialties, the individual team members often served on many teams at once). It may be that the team members were capturing relevant data, but they were doing so in a capacity that advocated their issue. Such advocation was appropriate and useful when based on accurate findings (such as done in these examples by Laura and Ericka), but can be potentially detrimental to the success of the document if done on inaccurate, or “wishful,” findings (as done in these examples by Tom). Again, I don’t believe that Tom’s reports were necessarily intended to deceive, but Tom appropriated what he wanted to see in the usability session and then reported those perhaps misappropriated results to the group.

Bias in What’s Omitted in the Usability Reports

While the evaluators appeared to highlight findings from UT that supported their predefined and ongoing design concerns, they also appeared to selectively omit findings that could be harmful to their concerns. The omission of findings from UT sessions was not necessarily problematic because “a too-long list of problem[s] can be overwhelming to the recipients of the feedback” (Hoegh, Nielsen, Overgaard, Pedersen, & Stage, 2006, p. 177), and that the desire for concise reports and the desire to explain results clearly and completely may be incompatible (Theofanos & Quesenbery, 2005). Indeed, only about 25% of the findings from the UT made their way (either accurately or inaccurately) into the oral reports. However, what is potentially problematic is that, although each evaluator had the opportunity, at no time did the evaluators present findings to the group that ran counter to a claim that the evaluators had made in a previous meeting. In other words, though the language or the actions of the UT participant could provide support against a previously stated claim, no evaluator presented that information in the oral report. For example, in a meeting two weeks prior to these oral reports, Laura suggested that a particular picture be used on the title page of the document because it is “funny, open, and inviting. It kinda says that everyone likes mail.” However, in her UT, P3 pointed directly at the photo and said, “This photo is scary.” Laura did not follow up with P3 to determine why P3 thought the photo was “scary,” nor did she tell the group that P3 thought the photo was scary, possibly because the finding would undermine her suggestion that the photo was appropriate for the document.

In another example, the team that developed potential titles for the document advocated the use of “A Household Guide to Mailing” out of several possibilities. In that meeting a month before the results of the usability evaluations were discussed, Ericka said, “[‘A Household Guide to Mailing’], you know, conveys a couple of ideas, like that it’s a household guide, that anyone, anywhere can manage this guide because everybody’s got a household of some kind, and the second idea is that it really distinguishes it from the small business mailers and the print houses, ‘cause this isn’t going to help them out.” In Ericka’s usability session, P1 said, “Okay, so this is a Household Guide to mailing. I’m not exactly sure what that means, what household means, but I guess that’s just me.” Again, P1’s statement in the usability session casts some doubt on the certainty with which Ericka advocated “A Household Guide to Mailing.” However, Ericka did not question P1 about her statement and Ericka did not include this finding in the oral report.

Each of the evaluators heard statements or observed actions in their usability sessions that did not support a claim they had made previously. But none of these evaluators reported those findings to the group. It may be that the evaluators consciously sought to omit the offending findings from the report, but it may be something less deliberate. Perhaps these evaluators, knowing they had a limited time frame to present the results of the evaluation, decided (rightly or wrongly) that the finding that contradicted their claim was not one of the more pressing issues revealed by the test. Indeed, previous studies have shown that even expert evaluators who are not conducting do-it-yourself evaluations and, thus, have less potential for bias, have difficulty agreeing in the identification of usability problems, the severity of those problems, and in the quality of their recommendations (Jacobsen, Hertzum, & John, 1998; Molich et al., 2004; Molich, Jeffries, & Dumas, 2007). These novice evaluators certainly had the same struggles (perhaps more so) as expert evaluators. It may be that, given that the stated goal of the evaluation was to determine the degree of success in navigating the document, that findings that did not relate to navigation were not given high priority in the oral report. However, of the 26 findings presented in the oral reports that stemmed in some way from the usability evaluations, only 6 (or 23.1%) dealt in some way (even highly tangentially) with navigation. Therefore, 77.9% of the reported findings dealt with something other than the primary issue of navigation, yet none of those reported findings ever contradicted a claim made previously by an evaluator. Given that this group so definitively declined to present evidence from usability testing that ran counter to their previously stated opinions, more research is needed to determine how influential personal belief and the desire to save face is in groups conducting do-it-yourself usability testing.

Biases in Client Desires

One, perhaps unexpected, area of potential bias came from the USPS clients. In a meeting a few weeks before this round of evaluation, several stakeholders from USPS headquarters stated that they were not going to pay for an index in a document so small. As one stakeholder said, “If you need an index for a 40-page book, then there’s something wrong with the book.” While the designers countered their client’s assertion by claiming that people read documents in “a multitude of ways, none no better than the other,” the clients repeated that they did not want to pay for the additional 1-2 pages of the index. Therefore, in the subsequent meeting, the project manager told the designers that “sometimes sacrifices must be made” and that they were taking the index out of the prototype.

In all three of the evaluations observed for this study, the usability participant mentioned at least once that he or she wanted an index. However, the desire for an index was not mentioned by any of the evaluators during the oral reports. It may be that these evaluators declined to include this finding in their report because both the clients and their project manager had made it clear that they did not want an index in the document. The desire to not present a recommendation that flies in the face of what the client specifically requested may have chilled the evaluators desire to report these findings. Perhaps if the evaluators had been more experienced or had felt as though they were in a position of power, they may have broached the unpopular idea of including an index. This reluctance to give bad or undesirable news to superiors has been well documented (Sproull & Kiesler, 1986; Tesser & Rosen, 1975; Winsor, 1988). Interestingly, after the next round of testing, one evaluator mentioned that his usability participant said, “if it doesn’t have an index, I’m not using it.” At that point, many of the previous evaluators commented that their participants also requested an index. Ultimately, the version of the document that went to press had an index.

Poor Interpretation Skills

Further, it may also be that these evaluators were not particularly adept at analyzing and interpreting the UT sessions. The protocol, the collection of data, and the lack of metrics may not have been ideal, but was certainly reflective of real-world (particularly novice real-world) do-it-yourself usability practice. The lack of experience on the part of the evaluators may explain why these evaluators clung to the sound bite findings—findings that were relatively easy to repeat but that may not reveal the most critical problems or the most pressing usability issues. Indeed, these evaluators were fairly good at accurately representing the sound bites, but struggled with representing more complex interpretations in their oral reports. It may be that, for example, Tom truly interpreted P2’s statement that he found a font “interesting” to be an indicator that P2 did not like the font, while other evaluators may have interpreted that statement differently. Studies on the evaluator effect have shown that evaluators vary greatly in problem detection and severity rating, and that the effect exists both for novices and experts (Hertzum & Jacobsen, 2001). This variation is not surprising given that user-based UT typically involves subjective assessments by UT participants, followed by subjective assessments of those assessments by the evaluator to determine what is important for document. It may be that, just as a variety of evaluators will have high variations in their findings, individual evaluators may show great variation in the findings they (consciously or unconsciously) choose to include, omit, or alter. As Norgaard and Hornbaek noted, while there is a plethora of information on how to create and conduct a usability test, there is “scarce advice” regarding how to analyze the information received from usability tests (2006, p. 216). Given that the “how” of UT analysis isn’t the primary goal of UT textbooks and professional guides, the fact that these novice evaluators struggled to accurately repeat findings obtained in the UT sessions in their oral reports may simply be a product of attempting to process the findings without a clearly identified system of analysis. Without such a system of analysis, these evaluators may have interpreted the findings in ways they think were appropriate, even when they countered the statements made in the UT session.

Limitations and Future Research

This descriptive, language-based case study, while careful in its observations, has, like all case studies, limitations; however, each limitation also provides an opportunity for future exploratory research into how evaluators assess findings from UT sessions. First, this case study is limited by the number of UT sessions observed. Future studies may expand the number of UT sessions to gain broader representation of the types of language end-users produce and the kinds of analyses and recommendations evaluators produce. Second, it is clear that this study is limited by its population of novice, not expert, evaluators. Indeed, the findings in this study might be amplified by the fact that the UT evaluators do not have significant experience in usability testing. However, studies by Boren and Ramey (2000) and Norgaard and Hornbaek (2006) that investigated experienced professionals found that what professional evaluators do often does not fall in line with guiding theories and best practices. Further, Norgaard and Hornbaek’s study of professionals found many similar issues to this current study of novices, including evaluator bias and confirmation of known problems. Additionally, while it may be tempting to presume that expert evaluators would show more consistency than their novice counterparts in the relay from raw data to reported finding, previous research on the abilities of expert versus novice evaluators in user-based evaluations is divided on which group is more effective and produces higher quality evaluations (Hertzum & Jacobsen, 2001; Jacobsen, 1999). Future studies that compare novice evaluations to expert evaluations may be able to establish a path of best practices, regardless of whether the evaluators are novices or experts. Third, this study explored only the oral reports of the evaluators. Perhaps written reports would reveal a differing analysis process and differing results than what appeared in this study.

In addition, direct questioning of evaluators may provide insight into how evaluators perceive their own analyses. How do they rate the quality of their analysis and the quality of the analyses of others? Do they believe that they have any biases? What justifications do they give for including some UT findings in their reports while omitting others? Do they perceive any difference between the types of findings they include (such as sound bite findings versus interpretation findings)?

Conclusion

While previous studies have investigated the agreement of usability findings across a number of evaluators, this study looked closely at how evaluators present findings in UT sessions in their own oral reports. This study has compared the language used by UT participants in UT sessions to the language used by evaluators in the reports of those sessions in order to understand the fidelity of the presented findings. This investigation has shown that many findings from the sessions do not make their way into the reports, and those findings that are in the reports may have substantial differences from what was uttered in the UT sessions. Therefore, for this group, the consistency and the continuity of the findings from session to report is highly variable. It may be that issues related to conscious or unconscious biases or poor interpretation skills may affect the way the evaluators presented (or omitted) the findings. Ultimately, this case study has shown that much is to be learned about how evaluators transform raw usability data into recommendations, and that additional research into such analyses for consistency and continuity is warranted.

References

- Bacon, F., Urbach, P., & Gibson, J. (1994). Novum organum; with other parts of the great instauration. Chicago: Open Court.

- Boren, M.T., & Ramey, J. (2000). Thinking aloud: Reconciling theory and practice. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 43(3), 261-278.

- de Jong, M., & Schellens, P. J. (2000). Toward a document evaluation methodology: What does research tell us about the validity and reliability of evaluation methods? IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 43(3), 242-260.

- Geisler, C. (2004). Analyzing streams of language: Twelve steps to the systematic coding of text, talk, and other verbal data. New York: Pearson.

- Gray, W.D., & Salzman, M.C. (1998). Damaged merchandise? A review of experiments that compare usability evaluation methods. Human-Computer Interaction, 13(3), 203-261.

- Hertzum, M., & Jacobsen, N. E. (2001). The evaluator effect: A chilling fact about usability evaluation methods. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 13(4), 421-443.

- Hoegh, R. T., Nielsen, M. C., Overgaard, M., Pedersen, M. B., & Stage, J. (2006). The impact of usability reports and user test observations on developers’ understanding of usability data: An exploratory study. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 21(2), 173-196.

- Jacobsen, N. E. (1999). Usability evaluation methods: The reliability and usage of cognitive walthrough and usability test. University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen.

- Jacobsen, N. E., Hertzum, M., & John, B. E. (1998). The evaluator effect in usability tests. Paper presented at the CHI 98 conference summary on Human factors in computing systems.

- Johnstone, B. (2002). Discourse analysis. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Krug, S. (2010). Rocket surgery made easy: The do-it-yourself guide to finding and fixing usability problems. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). An application of hierarchical Kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics, 33(2), 363-374.

- Molich, R., Ede, M. R., Kaasgaard, K., & Karyukin, B. (2004). Comparative usability evaluation. Behaviour & Information Technology, 23(1), 65-74.

- Molich, R., Jeffries, R., & Dumas, J. S. (2007). Making usability recommendations useful and usable. Journal of Usability Studies, 2(4), 162-179.

- Norgaard, M., & Hornbaek, K. (2006). What do usability evaluators do in practice?: An explorative study of think-aloud testing. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 6th conference on Designing Interactive Systems.

- Redish, J. (2010). Technical communication and usability: Intertwined strands and mutual influences. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53(3), 191-201.

- Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1986). Reducing social context clues: Electronic mail in organizational communication. Management Science, 32(11), 1492-1512.

- Tesser, A., & Rosen, S. (175). The reluctance to transmit bad news. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 8, 193-232.

- Theofanos, M., & Quesenbery, W. (2005). Towards the design of effective formative test reports. Journal of Usability Studies, 1(1), 27-45.

- Winsor, D. A. (1988). Communication failures contributing to the Challenger accident: An example for technical communicators. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 31(3), 101-107.