[:en]

Who do we exclude unintentionally or intentionally in the work that we do as designers and researchers?

To be good at what we do as UX practitioners, we need to be mindful and recognize the differences around us and accommodate solutions with a positive and inclusive outcome. How can we train ourselves to see exclusion early on?

We both believe that UX professionals do not intentionally exclude people from their work and believe that through coaching, designers and researchers can learn to recognize exclusion, be aware of their own biases, and design better products and experiences. In this paper, we share some tools and experiences that we have created to help UX professionals recognize exclusion.

What Is Exclusion?

We may already apply inclusive design practices in our daily work, but we do not always reflect on how exclusion is ingrained in our culture. To start the conversation about inclusion, we need to self-reflect on exclusion.

To exclude is to deny a person or group access to a place, a group, or a privilege. We may exclude intentionally or unintentionally based on race and ethnicity, gender, age, linguistics, or ability. These are some of the exclusion criteria that may be easier to identify. However, oftentimes we exclude unintentionally, for example, when we invite our friends over and assume that everyone eats meat; or if we always have work activities at times or in venues that parents with children will not be able to attend due to childcare responsibilities, or even in international teams, when we always schedule meetings in the middle of the night for our colleagues in other parts of the world. How might we include people that we unintentionally exclude?

To build a mindset of inclusivity, we have to learn to see exclusion and then build anti-exclusive practices and mental models.

To see how we exclude, we have to learn to see whose voice is missing, learn to be open to understanding different perspectives, and create space for plurality. In addition to recognizing exclusion, we also have to learn how to be attentive and listen to people when they feel excluded. The ability to be able to spot exclusion allows us to be the first responders for inclusion. While we may not include everyone in our practices, recognizing exclusion creates a mindset of mindfulness focused on the empathetic reduction of exclusion and greater inclusion, and both will lead to design practice that does not just serve a select few.

Unintentional Exclusion

Unintentional exclusion occurs almost like an instinct. These instinct-based behaviors are rooted in culture, geography, or even family history. The following are some examples of unintentional exclusion in a work environment:

Take a moment to reflect on how diverse your team is:

- Does your team have a balanced gender ratio?

- How many languages can the team speak collectively?

- Are there team members with permanent disabilities?

- When hiring a new team member, are black/brown candidates well represented?

Unconscious hiring bias is a systemic issue in the industry, and it happens in so many ways. However, it can be eradicated with:

- suitable interview training covering common hiring biases,

- a consistent and transparent hiring process, and

- a standardized interview guide to ensure every candidate is asked the same questions.

Before hiring, consider having a diversity activity with your peers to evaluate the benefits of having a multicultural and diverse team.

Toward an Inclusive Mindset

Inclusive design is not a methodology nor a framework. It is a mindset that takes us beyond our comfort zone, our bubbles, or our “caves,” as Plato would define in the classic The Allegory of the Cave, in which three men are imprisoned in a cave and do not understand the world outside. Unless we go outside of our own caves and see what is out there, we will not understand how to design for the outside.

Most of us are born in these caves, accumulating a limited amount of experiences and behaviors. Unintentionally, as we transition into our working environment, we translate these behaviors into decisions that will impact those that have never been in our caves. How can we have more conversations with people in different caves?

Over the years, businesses have also fallen into caves, adopting exclusionary practices, such as the 80/20 rule or the Minimum Viable Product (MVP), where they focus on the quickest and highest return possible. Both practices—unintentionally—could promote the exclusion of important groups that could define the success of your products and services in the long run.

Inclusive design practices help teams step out of their caves, observe, and appreciate the differences outside.

Inclusive Design Principles

The inclusive design team at Microsoft describes personal bias as the root cause for exclusion in product design. The team proposes three simple steps to overcome exclusionary practices (Microsoft, 2018):

- “Recognize exclusion”: Who or what group is being excluded? That is the first question that design teams should reflect upon. Once the exclusion is recognized, it becomes a design challenge to be addressed as a whole, not as a remediation effort.

- “Solve for one, extend to many”: From the moment we are born, the range of our abilities will continue to reach unexpected limits as we grow. Designing with accessibility in mind naturally removes our biases and improves the overall experience of our products and services. Nevertheless, considering those with technology or socioeconomic barriers will also take any design solution to a higher maturity level.

- “Learn from diversity”: How much do we learn when traveling abroad? What if you could bring the knowledge you do not possess from abroad into your team? Inclusive design teams are best equipped to address world-class challenges when representing a wide range of ages, gender preferences, socioeconomic background, cultures, languages, and abilities.

Protecting Our Work from Exclusionary Practices

In the work that we do as product and service design practitioners, we often receive business requirements that are, in fact, exclusionary. These exclusionary criteria are oftentimes not seen as “exclusion,” but rather as business criteria that impact the bottom line. If we are trained as inclusive practitioners to detect these “exclusionary triggers” early on, we can stop exclusion at its roots.

Who’s Being Excluded?

Exclusionary triggers are typically unintentional business practices that focus on the immediate and finite goals rather than on the long-term outcome. These exclusionary triggers can be better addressed with simple tools like asking, “Who’s being excluded?”

Exclusionary triggers may sound something like the following:

- “Let’s focus on the 80%…”—Who’s being excluded?

- “This is a Mac-only app”— Who’s being excluded?

- “Blind people don’t use our app”—Who’s being excluded?

- “Who’s your audience?”—Who’s being excluded?

- “Power users know how to navigate this issue…”—Who’s being excluded?

This list can go on, but how might we create inclusive practices that shield our research studies and design solutions from being influenced by these unintentional exclusionary triggers?

Consider addressing inclusion across your entire design process:

- User Research: Have a good representation of generations, race, gender, disabilities, and culture in your user interviews and usability studies.

- Interaction Design: Consider end-users living with technology barriers, such as low-bandwidth internet connectivity, low-end devices, and use of assistive technologies.

- Prototyping: Build prototypes to be tested with different populations, in different countries, and with people with disabilities.

- Visual Design: Annotate your final designs with accessibility instructions for proper development hand-off.

The benefit of the exclusionary trigger is actually an illusion. An exclusive lens is a lens of scarcity. Who do we automatically put in the 20% in the 80/20 rule?

- Black people?

- Poor people?

- Disabled people?

Do we mean an 80/20 rule for people in the United States or Worldwide? If you consider the 80/20 rule at a global level, which populations, languages, time zones, or beliefs will be excluded in the 20%?

Inclusion is not a zero-sum game: We do not have to prioritize this group over that group to win. Business does not lose by having inclusive mindsets. We can open our frame to include more and to consider the needs of the people who are intentionally and unintentionally excluded. Focusing on inclusion expands who can access goods and services. That is a win-win for everyone. So as a response to exclusionary triggers, we can ask questions that can promote greater inclusion such as: “Who else?,” “What else?,” “How else?,” “To what extent can we include…?”. How can we collaborate with the people who are normally excluded leading to better results? As designers and researchers, we can learn to use inclusive framing in the way we create focus in the work we do.

Toward More Balanced Inclusion

In addition to learning to recognize exclusion of an individual, there are several other levels that we should constantly examine to see if they are inclusive or exclusive:

- The team level: How diverse are our teams? Do they reflect the diversity of the people that they serve or could be serving? Is there diversity in age, gender, sexuality, income, education level, and ability status? How can we consciously make our teams more diverse?

- The end-user level: Do we understand who the end-user will be? If this group is not diverse, why is it not? Can we intentionally address the needs and concerns of gay people, poor people, black people, disabled people, and other sometimes invisible groups? How will we understand these many perspectives? This brings us back to our teams. Diverse teams will design better products for diverse audiences.

- The business level: Can product stakeholders adopt inclusive practices with the understanding that it is good for the business? Having inclusive products increases the quality of products and services, and it is good for the business. Moreover, retroactively addressing inclusion and accessibility flaws is expensive and creates monumental liability risks.

- The technological level (high-end vs. low-end): Does the product cater to diversity in technological access? What is the experience of people with limited connectivity or data bandwidth? Whom do we exclude by some of the technological constraints of the products and services that we create? How can we open the constraints to be more inclusive?

A Selection of Tools to See Exclusive Practices and Promote Inclusion

So far, we have been focusing on recognizing exclusion. In this section, we will concentrate on sharing tools that we have created to help designers and researchers to develop the instinct to recognize exclusion, reveal their own biases, and spread inclusive habits across organizations.

The Positionality Wheel: Making Biases Explicit

It can be difficult to see where one’s personal biases may lie. In qualitative research, researchers delineate their positionality, which means that they reflect and describe their identity and worldview and how these impact their work. This is often presented in a “positionality statement,” where one can reflect on their positionality to understand where their biases might lie. Bringing elements of our identities and our biases to the forefront can help us see which of our own practices might be exclusionary.

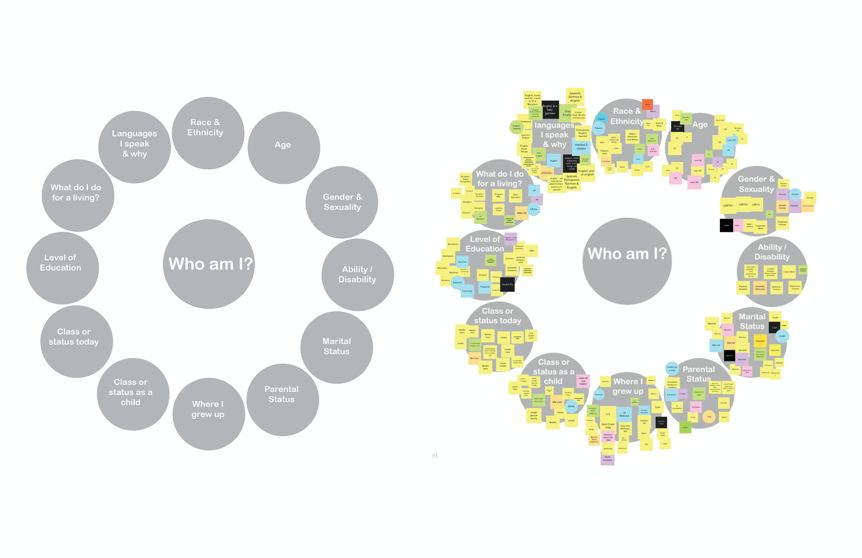

Figure 1. On the left the Positionality Wheel, and on the right, a Positionality Wheel that has been completed by students in a class. (Created by Noel, 2018.)

The Positionality Wheel (Figure 1) is an activity created to help designers and researchers reflect on their identities and their teams’ composition before starting their work. The wheel was developed around elements that could help a researcher write a positionality statement. This activity encourages all participants to reflect on their identity facets from more visible factors such as race, gender, age, and other invisible facets, such as ability status, class, education, and even their languages.

To use the tool, participants reflect on the 12 elements of their identities. They then complete the worksheet individually or as a group. The worksheet can be completed by hand or digitally using a virtual whiteboard.

With the recent demand for remote working, we began using the Positionality Wheel as a virtual activity, which led us to a change from being an individual reflection to a group discussion. A group setting clearly helps teams visualize their heterogeneity or homogeneity as a team. Responses to the wheel are posted anonymously on a virtual whiteboard.

Teams can discuss the users’ profiles they are supporting and see if the team possesses the diversity level required to understand the context. They can then reflect on how to calibrate the teams to include greater diversity as needed.

Understanding positionality helps teams identify their own biases and gaps, learn how to recalibrate their composition, and balance ideas.

If we want to practice inclusive design, we need to foster inclusive and diverse teams that will constantly make us re-evaluate our assumptions and help identify different challenges and opportunities that team members of a dominant culture would never see.

Positionality Radar Chart

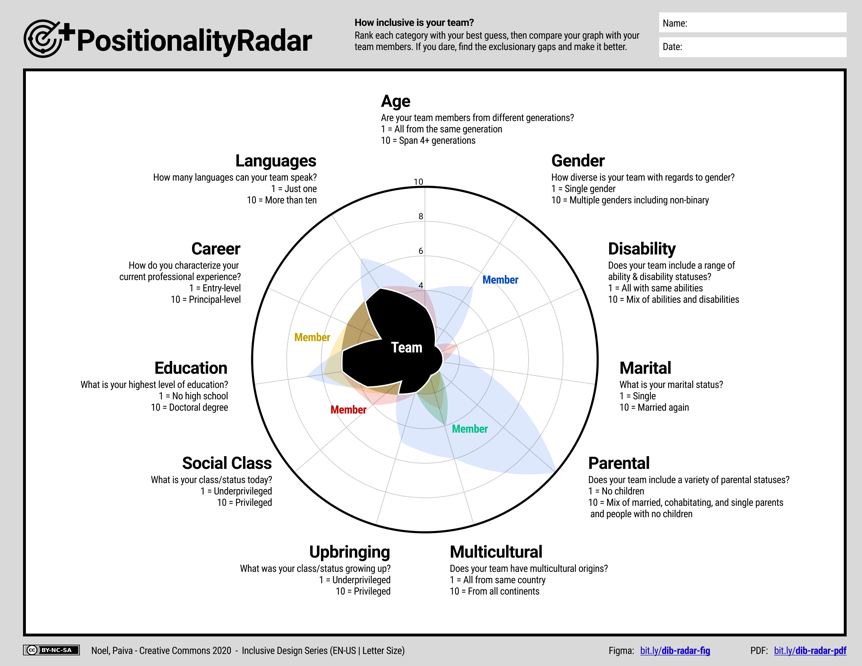

We are constantly experimenting with how we visualize positionality to help teams recognize exclusion. We recently created a visualization as a variation of the Positionality Wheel (Figure 1)—the Positionality Radar chart. Teams would be able to visualize how “off-balance” their perspectives may be by using this chart (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Positionality Radar worksheet is an activity to help teams visualize where they may need to calibrate its inner diversity. Each color represents the profile of a different user. The team can then reflect on the shape of the image created by the overlapping profiles and understand how the team profile affects how they address the issue they are tackling. (Created by Noel & Paiva, 2020.)

The Designer’s Critical Alphabet: Seeing Exclusion Through New Language and Questions

The Designer’s Critical Alphabet was created in 2019 as a means of introducing critical literacy to designers (Noel, 2020). Each card introduces a concept to designers then has a prompt to make the concept more relevant to design or research practice.

The cards were born out of an interest in introducing language and questions that, through reflection, might improve the way we approach problem-solving, research, and collaborative practices as UX professionals. This gamified format and prompt questions were used to make the social justice-focused content more accessible and applicable to a non-academic audience.

Though the resource was created for designers, it is used by many other professionals such as researchers, human resource specialists, social workers, and public health practitioners.

The deck includes research paradigms such as emancipatory or transformative research, theories like critical race theory and feminist theory, and concepts about exclusion, including assumptions, linguistic hegemony, and xenophobia. Furthermore, these cards present some reflective, self-focused prompts like unlearning oppression, values, and self-awareness.

Figure 3. The Designer’s Critical Alphabet was designed to introduce designers to critical theory and prompt action through reflective questions. (Created by Noel, 2019.)

Designing for Your Future-Self to Anticipate Disabilities

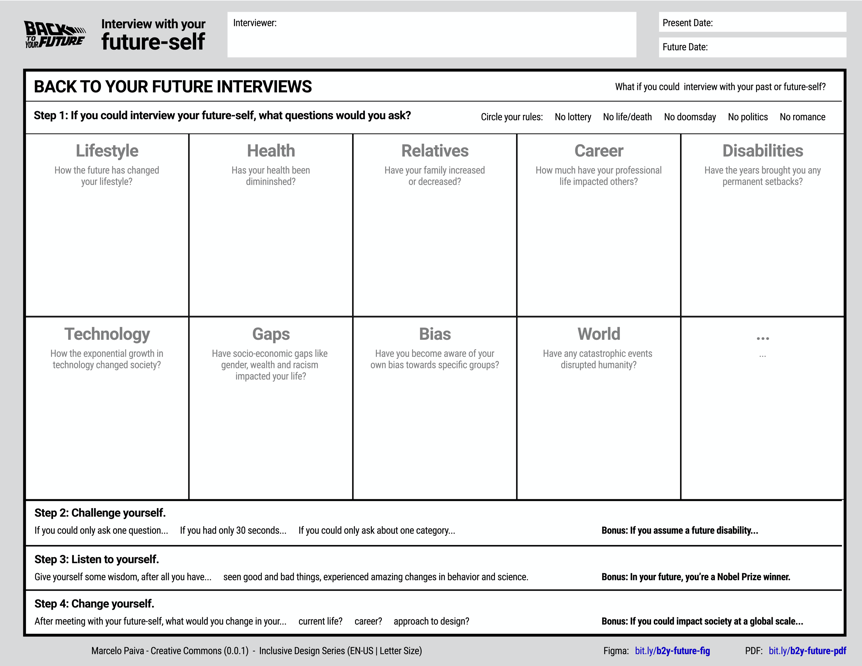

Figure 4. The “Interview your future-self” worksheet. (Created by Paiva, 2020.)

In the playful “Interview with your future-self” worksheet, Paiva (2020) challenges researchers and designers to time travel and to interview themselves in the future.

The idea for this worksheet was sparked by Donald Norman’s reflection on how many products are badly designed for older adults and the lack of understanding of the needs of older adults (Norman, 2019). When using the worksheet, you can choose to interview your past or future self to reflect on lifestyles, health, career, and other areas of different periods in a life.

This worksheet focuses on creating an inclusive mindset from the standpoint that a lack of disability is, in fact, only temporary. Awareness of future disabilities or lifestyle changes could make us more aware of whom we are excluding today. If UX professionals anticipate that they will lose their current abilities, they will develop more inclusive mindsets.

Conclusion

Developing an inclusive mindset requires practice. As we practice recognizing exclusion, we begin to see it in places that we did not see before. We see how we exclude on local levels and global levels. We learn to remember to ask people their pronouns and how they would like to be addressed, and we remember to include a vegetarian option when preparing dinner for our new guests.

Recognizing exclusion brings us to a more inclusive mindset, regardless of the size of the design challenge we are facing. As we practice recognizing exclusion, challenging embedded anti-inclusive practices, that are perpetuated “just because,” becomes second nature.

We begin to see that things do not have to remain as they always were. A clear move towards anti-exclusion also brings us to designing for plurality and the normalization of multiple narratives. We seek to better understand the points of view that we exclude.

This is an amazing time to begin on an inclusive path as a designer. This industry is still morphing, evolving, and maturing. Everyone in industry needs to learn to design for accessibility and inclusion.

Our Positionality: Who Are We?

We both have focused on inclusive design in different ways. We write as two professionals in design from similar yet different positions.

Lesley-Ann Noel: I come to this work about inclusive design as a designer from Trinidad and Tobago. I have lived and worked in several different countries, including Brazil, Uganda, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Kenya. I came to the United States in 2015. I have an outsider perspective and see both how people who are outside of the dominant group are at times invisible or excluded from mainstream narratives, both as designers and as consumers. I understand the value that outsider perspectives bring to process. In my work I seek to introduce designers to critical language and theory, as well as to share reminders and tips that might help make them more perceptive about inclusion.

Marcelo Paiva: I arrived in the United States in 1992 from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. My digital design practice evolved with the industry, from computer-aid drafting (CAD) to graphic design, desktop publishing, then web/mobile design and development. Nowadays, I lead user experience design and research teams for large corporations, consult with startups, build efficient cross-functional teams, and lead monthly UX community events in South Florida to advocate for accessibility and inclusive design. I am a proud American citizen, having lived longer in the United States than in my native country, Brazil. For the native Brazilians, I am just another “gringo,” and for the native Americans, I am still an immigrant from Brazil, which leaves me feeling excluded everywhere I go.

Both authors understand exclusion from their positions as an immigrant/foreigner, non-English speaker/English-speaker with a different accent, person of color, and so on. They bring these perspectives to their work to try to make design more accessible to people from diverse backgrounds.

References

Microsoft (2018). Inclusive Design. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://www.microsoft.com/design/inclusive/

Noel, L.-A. (2018). Home: Lesley-Ann Noel. The Positionality Wheel. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://lesleyannnoel.wixsite.com/website

Noel, L.-A. (2020, November 17). A designer teaches people how to see others who are not like them. Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/601804/a-designer-teaches-people-how-to-see-others-who-are-not-like-them/

Noel, L.-A., & Paiva, M. (2020). Positionality radar (worksheet).https://bit.ly/dib-radar-pdf

Norman, D. (2019, May 07). I wrote the book on user-friendly design. What I see today horrifies me. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/90338379/i-wrote-the-book-on-user-friendly-design-what-i-see-today-horrifies-me

Paiva, M. (2020). Interview with your future-self (worksheet). https://bit.ly/b2y-future-pdf

[:]