Abstract

Most companies today place their job

advertisements online and frequently require that applications for jobs be

submitted online. Unfortunately, many online employment Web sites are

inaccessible to users with disabilities, preventing these individuals from

even applying for jobs online. Previous studies have used automated tools or

expert reviews to evaluate the accessibility of online employment

applications. This study involved 16 blind, screen-reader users, attempting

to apply for jobs online. Two applications were submitted to each of 16

companies in the southeastern United States, for a total of 32 applications

submitted. Many of the online employment application processes were

inaccessible to blind users, and users repeatedly asked for assistance from

the researchers when they faced accessibility problems. Only 9/32 (28.1%) of

application attempts could be completed independently without any

assistance. This report details the problems discovered during the usability

testing and discusses the most common problems for blind users, as well as

problems related to general usability. It also provides suggestions for

improvement, including providing accessible feedback, unique and clear

hyperlink text, properly structured layout, logical grouping of questions,

clearly identified data format and required form fields, and conducting

regular accessibility evaluations. It is essential that companies ensure

that their online employment applications are accessible and usable for all

individuals, including individuals with disabilities.

Practitioner’s Take Away

The following are key points for practitioners from this study:

- Usability testing of Web interfaces should include individuals with disabilities in order to verify that an interface can be used by all individuals. It is not enough to simply assume such usability based on automated accessibility evaluations. This is especially true in transactions or applications where multiple subtasks must be successfully completed to reach the task goal.

- When conducting usability tests with blind participants, we suggest that the length of the session should be estimated in advance so that participants can be informed in advance of the usability testing session.

- When conducting usability evaluations of interfaces with individuals who are blind, it is sometimes necessary to consider a modified approach to usability testing, in order to ensure that the usability of the entire interface is evaluated, rather than relying on a limited evaluation due to possible accessibility obstacles that are discovered during the usability testing.

- In addition to observing users during usability testing, encouraging users to think aloud may help to identify more issues during the testing exercise.

- Many of the core usability problems for people with disabilities are actually the same usability problems as for people without disabilities.

Introduction

Employers today commonly place job advertisements

and applications online (Braddy, Meade, & Kroustalis, 2008; Bruyere,

Erickson, & VanLooy, 2005; Nakamura, A., Shaw, Freeman, Nakamura, E., &

Pyman, 2009), and job recruiters consider online job applications to be

fast, efficient, and cost-effective. Many job seekers view online

applications as both convenient and enhancing their prospects of securing

jobs (Breen, 2000; Capellli, 2001; Meskauskas, 2003; Younger, 2008).

Individual companies advertise jobs on their Web sites or outsource the

task to recruiting companies or job boards, which also place the jobs

online (Williams & Verhoeven, 2008). Both sighted and non-sighted (blind)

job seekers go to the same sources online to search and compete for jobs,

but many Web sites that post these jobs are not accessible to blind people

who depend on assistive technologies to access Web sites (Bruyere,

Erickson, & VanLooy, 2005; Lazar et al., 2011). The purpose of this

project was to evaluate the level of difficulty that blind users have when

attempting to submit job applications online, and to determine what

specific components of the application (e.g., finding an open position,

previous education, references, account creation) cause the greatest

problems. Previous usability evaluations of employment Web site

aggregators, such as hotjobs.com and careerbuilder.com, focused on using

assistive technologies and expert reviews (Bruyere, Erickson, & VanLooy,

2005; Lazar et al., 2011), but no usability testing involving individuals

with disabilities attempting to apply for jobs online has previously been

conducted. The goal of this project was to evaluate the accessibility and

usability of online employment Web sites, by having blind users attempt to

apply for jobs online.

Background

Employment is a core ingredient in self-esteem,

independence, and happiness (Frey & Stutzer, 2002). In a recent study in

the UK to measure the nation’s wellbeing, having a job was linked to

happiness and self-esteem (Ross, 2011), and unemployment has been shown to

have a negative effect on happiness (Frey, 2008). Historically, the

unemployment rate for people with disabilities, especially blind

individuals, is high (Wang, Barron, & Hebl, 2010), despite the fact that

blind people want to work and be productive, pay taxes, and be financially

independent (National Federation of the Blind [NFB], 2010). As an example

of how accessibility challenges hinder blind people who want to work, a

study has shown that computer frustrations (such as inaccessibility of Web

sites) can negatively impact the mood of blind individuals, but only when

it impacts their work (Lazar, Feng, & Allen, 2006). In the US, about 70%

of working-age blind people are unemployed (NFB, 2011), and the estimates

in other countries also reflect high unemployment—about 66% in the UK

(Royal National Institute of Blind People [RNIB], 2011a) and about 75% in

Canada (Canadian Federation of the Blind [CFB], 2011). This figure is high

compared to the general unemployment rate of approximately 8.6% in the US

(Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS], 2011), 8.3% in UK (Office for National

Statistics [ONS], 2011), and 7.4% in Canada (Statistics Canada [SC],

2011). It is obvious that the goal of equal employment for the blind is

still far from being realized.

Today, the recruitment world has moved from the

traditional method of job advertisement (handbills, job boards,

newspapers, etc.) to online advertisement (news, social networking, blogs,

job boards, recruiting Web sites, employer Web sites, etc.). There is a

proliferation of general online job application Web sites (often known as

“job aggregator Web sites”), and most companies also advertise job

openings on their own Web sites. Convenience, scope, efficiency, and

cost-effectiveness among other factors, have endeared many job seekers,

employers, and recruiting companies to prefer the online approach

(Capellli, 2001; Mehkauskas, 2003; Younger, 2008). For blind people who

use assistive technologies to access the Web, the opportunity to apply for

jobs online could, theoretically, be good news, however, inaccessible job

application Web sites actually lead to discrimination and an inability to

even apply for a job (Hastings, 2010; Everett, 2011).

Legal Status of Employment Web Sites

Currently, there have not been any known court

cases in the US relating to the legality of inaccessible online employment

applications. Online employment applications are likely covered under

Section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act of the US, which requires that all

employers that have federal contracts or subcontracts of at least $10,000

“must take affirmative action to hire, retain, and promote qualified

individuals with disabilities” (60-741.1).In July 2010, the Office of

Federal Contract Compliance Programs at the U.S. Department of Labor

issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) to strengthen the

regulations relating to Section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act, and the

ANPRM included a question (#13) relating to accessible online hiring

processes, with comments due on September 21, 2010 (Department of Labor

[DOL], 2011). Specifically, the text of the ANPRM was “What impact would

result from requiring that Federal contractors and subcontractors make

information and communication technology used by job applicants in the job

application process, and by employees in connection with their employment

fully accessible and usable by individuals with disabilities?1

What are the specific costs and/or benefits that might result from this

requirement?” No further action has been taken yet by the Department of

Labor related to this advanced notice of proposed rulemaking.

Within the Americans with Disabilities Act, Title I

addresses discrimination in employment, and Title III addresses

discrimination in the 12 categories of “public accommodations.” The ADA

was signed into law in 1990 before the advent of online employment Web

sites. However, since the mid-1990s, U.S. Department of Justice statements

and various court rulings (such as National Federation of the Blind vs.

Target) have stated that the Americans with Disabilities Act does apply to

Web sites of public accommodations. Furthermore, the Department of Justice

began the rulemaking process in 2010 for creating specific guidance for

Web accessibility within the ADA, with an advanced notice of proposed

rulemaking, titled “Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability;

Accessibility of Web Information and Services of State and Local

Government Entities and Public Accommodations” (Department of Justice

[DOJ], 2010). While the ANPRM does not specifically mention online

employment applications, it is expected that online employment

applications would be automatically covered as a part of the requirement

for accessibility of the Web sites of public accommodations.

Many other nations have supported the call to make

Web sites accessible to people with disabilities that use assistive

technologies (Lazar et al., 2011). Laws have been enacted, such as the

Equality Act 2010 in the UK (RNIB, 2011b), and the Financial

Administration Act (containing Common Look and Feel standards) in Canada

(Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat [TBCS], 2007). The World Wide Web

Consortium has also developed standards and guidelines for designing

accessible Web sites (W3C, 2011a). However, the goal of a fully accessible

Web is far from being realized, as research has shown that many Web sites,

including Web sites required to be accessible by law (such as government

Web sites covered by Section 508) aren’t accessible (Olalere & Lazar,

2011).

Previous Evaluations4

A number of evaluations have previously been

conducted on the accessibility of employment Web sites, but these

evaluations used automated tools, expert inspection, or a combination of

both. Previous research has not involved having blind users attempt to

apply for jobs online. In addition to validating that the problems

identified by automated tools or expert reviews are real, user-based

testing may clarify what the problems are, and identify additional

problems. While usability testing takes additional resources to conduct,

it provides more depth about problems and solutions. Furthermore, while

expert reviews can be most effective for evaluating compliance with

regulations on one Web page, usability testing with people with

disabilities is most effective in determining whether people with

disabilities can successfully complete a task involving a series of

interrelated subtasks, such as applying for a job online or completing an

e‑commerce transaction, or requesting government benefits (Lazar et al.,

2011).

Many job application Web sites have been found to

be inaccessible. Bruyere, Erickson, and VanLooy (2005) conducted an

accessibility evaluation of 10 job boards and 31 e-recruiting Web sites

for accessibility using an automated evaluation tool (Bobby v3.2) and an

expert-simulation of the application process using a screen reader. From

the results, none of the job boards evaluated were accessible; a majority

of the e-recruiting Web sites were inaccessible and only three out of the

12 corporate Web sites were accessible enough for the expert-simulated

process to go through. Lazar et al. (2011) also performed accessibility

evaluations on eight job aggregator Web sites. Aggregator Web sites (such

as careerbuilder.com and hotjobs.com) are those that provide job postings

from multiple employers and allow users to submit applications directly

through the site for many of those employers (Williams & Verhoeven, 2008).

Lazar et al. (2011) used expert inspections to determine job aggregators’

Web site compliance with Section 508 guidelines. The results showed that

seven of the eight employment aggregator Web sites evaluated had

accessibility violations.

1For example, requiring that contractors ensure that application

and testing kiosks are fully accessible and usable by individuals

with disabilities, and that contractors strive to ensure that

their Internet and Intranet Web sites satisfy the United States

Access Board’s accessibility standards for technology used by the

Federal Government and subject to section 508 of the

Rehabilitation Act.

Methods

This study focused on evaluating the accessibility

and usability of online employment application Web sites in eight

southeastern US states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, North

Carolina, South Carolina, Mississippi, and Tennessee. These states were

chosen because they are the states served by the Southeastern ADA Center

(http://adasoutheast.org/), which funded this project. Also, the

Southeastern ADA Center has connections with businesses in these states,

so the results of the usability evaluation can be communicated to

companies in the southeastern US, and could result in the improved

accessibility of online employment Web sites. The staff of the

Southeastern ADA Center chose two companies that had online employment

applications from each of the eight states, for a total of 16 Web sites

evaluated. For each state, the largest 50 employers were selected. Then,

in each state, the top 10 high growth fields were selected. Then, two

companies were selected from the 10 top growth fields in each state,

making sure that no field was represented twice in the sample. This way,

not only would there be geographic diversity, but also diversity of

different fields and industries. So as not to embarrass any of the

companies, they will not be identified by name. Two attempts were made to

apply for jobs on each Web site (for a total of 32 attempts at submitting

a job application).

Participants

A total of 16 participants were involved in the

usability evaluation. Most participants were recruited through a

partnership with the Maryland Division of Rehabilitation Services, Office

of Blindness and Vision Services. Participants were required to be blind,

at least 18 years of age, must have been employed at some point within the

last few years, and must be screen-reader users unable to use screen

magnification (meaning that the participants did not have enough residual

or partial vision to use their vision in the usability evaluation). It was

also stated in the recruitment email that the testing would require an

average of three to four hours per participant. Note that one participant

showed up for data collection, but it was determined that the participant

did not meet the screening qualifications. No data was collected from that

user, and a replacement user was selected. All 16 participants were

currently either unemployed or part-time employed, and were seeking

full-time employment. None of the participants were fully employed; so,

the participants were very representative of the typical blind persons who

would be attempting to apply for jobs online. Of the 16 participants, 11

were female, and five were male, and the average age was 36.5 years (with

a range of 21-65 years old). All of the 16 participants were blind users

with a great deal of experience using screen reader technology (an average

of 12.06 years of experience) and a great deal of experience using the

Internet (an average of 10.94 years). Three of the participants had never

applied for a job online before, but the other participants had previous

experience applying for jobs online. Of the 16 participants, two had high

school degrees, three had Associate’s degrees, nine had Bachelor’s

degrees, and two had Master’s degrees. Participants were paid $250 for

their participation. While some participants took public transportation,

others had friends or family members drop them off, however, the

friends/family members were not allowed to stay in the computer room or

assist the usability evaluation in any way. There was a 5-to-15 minute

break in between the two attempts to apply for applications. Participants

did not have any additional documented disabilities, aside from their

vision loss. Note that while the university Institutional Review Board

(IRB) requires signed paper copies of both the IRB form and the payment

form, printed copies logically do not make sense for blind participants,

so the participants received electronic copies of the documents in advance

that they could read. When the participants arrived for the data

collection, they were asked to sign the paper copies, with Braille

stickers saying “sign above” to let them know where to place their

signature.

No personal participant information was used, and

each participant had a name, resume, and email account prepared for them

for use in the study. All resumes submitted were marked “not a real

application—submitted for training purposes only” so as not to confuse or

waste the time of employers who received the application. There was no

stated time limit for how long it took participants to attempt to submit

an employment application.

Data Collection

For the data collection, participants were given

the URL of the home page of the company/organization and were told to

apply for a job of a certain category (e.g., help desk manager, or

software engineer). We interacted with all of the job application Web

sites beforehand to know which jobs were available on each Web site.

Specific job categories were selected for our participants in advance, and

resumes appropriate to each specific job were created for use by the

participants (for instance, with appropriate professional experience,

degrees, and certifications). All usability evaluations took place using

the same computer in the computer lab at the Maryland Division of

Rehabilitation Services, Office of Blindness and Vision Services. The

computer was a Dell Optiplex 760, Intel Core 2 Duo CPU, running Microsoft

Windows XP Professional Service Pack 3 and JAWS 11 (screen-reader

software). Users were allowed to modify the speech output speed to their

liking to make it similar to how they typically interact with a computer.

The browser used for the study was Internet Explorer 8. All data

collection took place in August and September 2011. JAWS was selected

because it is the dominant screen reader currently in use (WebAIM, 2010).

Typically, the participants were in the computer lab for 3-4 hours,

including the introduction, signature of forms, description of procedures,

the actual usability evaluation, breaks, and wrap-up.

We used a modified usability methodology to learn

as much as possible about the barriers to online job applications.

Ideally, people with disabilities need to apply for a job online without

assistance from anyone. Because many of the sites had core features (such

as the “search jobs” function) that were inaccessible, if a traditional

usability methodology had been used, the researchers could not offer help

or assistance in any way, and the participants would not have made it past

initial inaccessible screens. That scenario would have provided no useful

feedback about the accessibility of other steps in the hiring process. In

the modified usability methodology, when participants could not move

forward and specifically asked for help, we offered to assist them, and

took careful notes of when we were asked to perform an intervention and

the type of intervention performed. Specific data about the interventions

are in the Results section of this paper. Aside from the user-requested

interventions, we non-obtrusively took notes about what steps the users

were taking, and we did not comment or assist the users in any other way.

We encouraged the participants to think aloud and state what they were

doing, and that also influenced our notes.

Applying for a job online is really one large task

with a number of subtasks. These subtasks cannot be separated out as

separate, discrete tasks, because the tasks all must be completed

successfully to reach the ultimate user goal: submitting an application.

The specific subtasks for each Web site application process vary; there is

no consistency among sites in the different subtasks needed to reach the

goal. In comparison, when attempting to use different email applications,

all applications have identical, discrete tasks that can be compared

across different applications, such as adding an email address to an

address book, sending an email, responding to an email, and deleting an

email (Wentz & Lazar, 2011). While some subtasks are common across job

application sites (such as education, certifications, and previous work

experience), they are asked in a different manner, with differing levels

of detail required (e.g., one site asks you to name your university

attended, but another site asks you to find your university attended from

a list of thousands of universities). The same question is asked in

different ways on different sites: some ask a question as one question,

while some sites break that same question down into multiple subtasks.

Furthermore, different job application Web sites have different subtasks,

such as salary requirements, date availability for a job, availability for

job travel, hobbies, languages spoken, and work preferences, which often

are not asked on many of the Web sites. Some Web sites allow you to upload

a resume, and the software on the Web site then takes the data directly

from the resume, populates the form fields, and simply asks for

confirmation that they are correct. Other sites, even with a resume

uploaded, do not populate the form fields with any data. Therefore, it is

impossible to compare the performance on each subtask across sites, even

when those sites use a similar software package for the hiring process,

such as the recruitment software from Kenexa (http://www.kenexa.com/recruitment-technology).

Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted with two blind

participants to test the appropriateness of our data collection methods.

Note that this did not take place at the location described for the 16

participants, but rather took place in the participants’ homes. From the

pilot studies, minor modifications were made to the data collection

methods, such as a stronger encouragement to participants to think aloud,

clearer pre-study instructions, methods to document the interventions, and

increasing the amount of information available to participants on their

resumes for use in the study.

Results

Each participant was asked to apply for two job

openings online. One of the participants had to leave early, and therefore

could only attempt to submit one job application online. One of the other

participants, who had a more flexible schedule, was asked to attempt to

apply for a third job. Out of the 32 attempts to submit applications

online (two for each of the 16 companies), 24 of those attempts were

successful, that is, participants completed the application process.

However, many of those attempts involved interventions. Only nine of the

32 applications were submitted successfully and independently, without any

type of intervention, for a task success rate of 28.1%. The types of

interventions are discussed in the following paragraphs. For the nine

participants where both of the applications were successfully submitted,

for eight of those participants, the second application was completed and

submitted in a faster time period than the first application, suggesting

that over time, there could potentially be some learning effects if users

are submitting, for example, 10-15 employment applications online.

The quickest successful submission took 23 minutes, with no interventions. The

longest successful submissions were in 121 minutes, one with no

intervention and the other with one intervention. The longest unsuccessful

attempt lasted 229 minutes (nearly four hours), at which point the

participant gave up and indicated that they would not continue applying

for the job. It is important to note that, before the data collection

began, it was clear to the researchers that many of the sites use the same

software applications to power their job application processes. For

instance, four of the companies selected for the study use the Taleo

software (http://www.taleo.com/solutions/recruiting),

and four of the companies selected for the study use the Kenexa software.

It is important to note that each implementation of the Taleo and Kenexa

software packages is different (and there are multiple versions of the

software from those vendors), so while there are some similarities, each

company using Taleo or Kenexa is in fact using a different, but similar

interface.

Interventions

It is important to note that there were a total

of 34 interventions required, where participants asked for assistance in

moving forward. These interventions were in situations where a mouse click

was required (16), or where participants asked for suggestions (18). For the

16 situations where a mouse click was required, 12 of them were situations

on four sites. Often, a mouse click was required to access any information

about jobs. The other four situations where a mouse click was required were

for buttons that were inaccessible by keyboard use only. For instance, in

Figure 1, participants were required to click on the item to search for

jobs, but the object could not be selected using the keyboard. In Figure 2,

the two individual buttons were both read by the screen reader as

“previousnext,” allowing no individual identification of the buttons, even

though visually they appear as two clearly separate buttons.

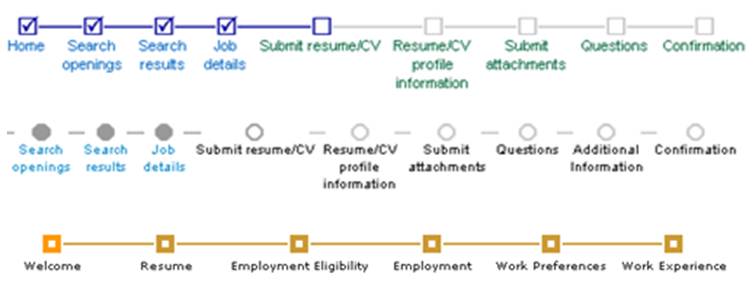

Figure 1. Screenshot of an inaccessible link

to search for jobs on a Web site that required a mouse-click

![]()

Figure 2. An example where two buttons were

visually separate, but in the code they were marked with the same label of

“previousnext”

The other 18 interventions occurred in situations

where the participants asked for a suggestion to help them move forward.

The causes of interventions were the following: (a) labels or markup were

misleading or absent (5), (b) the instructions from the Web page were

confusing (3), (c) there were pop-up boxes with inaccessible information

(3), (d) there was an error message where the Web site had rejected the

participant data input because it was not in the proper format (3), (e)

lack of participant knowledge (participant was listening too fast or could

not figure out how to attach a document; 2), and (f) JAWS problems (JAWS

was not reading the current Web page, and JAWS was not reading the options

in the combo box; 2).

Common Problems for Blind Participants

From the usability evaluation by the 16 blind

participants, patterns emerged of common problems in the online employment

applications. Some of these problems were specific to blind participants

who were accessing the employment applications using screen readers, but

other problems that challenged blind participants were more general

usability problems that blind users, as well as users with other

disabilities or users with no disabilities would face. Table 1 lists the

most common participant problems with the number of participant-requested

interventions, the number of Web sites impacted (out of 16), the number of

job applications impacted (out of 32), and the total number of instances

that a particular usability challenge occurred. The problems described

were either problems that were mentioned by the participants as

challenging during the attempts to apply for jobs, or identified and

defined by the researchers based on participants seeming to have problems

but not saying anything. Because we took a hands-off approach to testing,

just using instances in which participants specifically asked for help

would have greatly underestimated the number of problems. Therefore, we

also included instances based on observations where users were clearly

having problems but were not complaining.

Only problems that impacted 10 or more applications

are listed. For example, one cause of intervention mentioned earlier, lack

of participant knowledge (with two interventions), did not appear in Table

1 because it did not occur frequently enough to meet the described

threshold of impacting 10 or more applications. Typically, when usability

problems are summarized after a series of usability evaluations, these

problems are summarized and prioritized, and therefore, because we could

not list every single problem in the article, we only focused on including

those that appeared most often. To provide context information for the

problems that required an intervention, the interventions are also listed

in the first data column.

Table 1. Common Participant Problems with

the Online Employment Applications, Sorted by Number of Applications

Impacted

|

Problem Description |

# of participant requested |

# of Web sites impacted (out of 16) |

# of applications impacted (out of 32) |

Total # of instances (no limit) |

|

Design problem/confusing layout/links: This includes general design issues that |

1 |

15 |

24 |

51 |

|

JAWS issues: These are problems observed from the way |

2 |

15 |

23 |

46 |

|

Instructional/labeling problem: This includes no instruction or title on |

3 |

14 |

22 |

36 |

|

Form control issues: An example would be no binding between |

0 |

12 |

16 |

19 |

|

Required fields unclear or unspecified: This would include unspecified required |

2 |

10 |

16 |

18 |

|

Finding jobs link: This refers to the inability to find jobs |

0 |

9 |

15 |

17 |

|

Mouse only/Flash/Javascript issues: This includes mouse-overs for accessing |

19 |

9 |

15 |

21 |

|

Skip navigation issue: Either skip navigation is not present, or |

0 |

9 |

13 |

13 |

|

Specific participant preferences: This included participants wanting multiple |

0 |

10 |

13 |

20 |

|

Tab order/cursor control: This would be illogical tab order, cursor |

0 |

10 |

13 |

16 |

|

Data input format: Examples of this would include unspecified |

3 |

11 |

13 |

14 |

|

Table headers poorly coded: Table headers were not properly labeled, |

2 |

7 |

10 |

11 |

“Specific participant preferences” is a category

that needs further explanation. For instance, participants noted that they

had preferences about how to enter the data, such as having multiple Web

pages to enter data, instead of one long page. This method allows a

participant to focus on one section at a time, and data is then saved from

one page to another (so that data is not lost if the session times out).

Also, participants preferred having an option for text entry, for instance,

either to upload a cover letter in word format or to copy and paste it into

a text box. If a resume was already uploaded, participants preferred to have

the resume automatically populate many of the data fields (which was an

option offered by a number of sites).

Action Items to Improve the Usability of Application Web Sites for Blind Participants

From the usability evaluation by the 16 blind

participants, patterns emerged of common problems in the online employment

applications. Based on the usability testing, the feedback by

participants, and the categories of problems that participants faced, we

created a list of five suggested action items to improve usability

specifically for blind users on employment Web sites. In the following

sections, we provide five action items that would both improve usability

for blind users as well as other user populations. All of these items are

actionable, with minor technical changes that would lead to great

improvement for blind users.

Design introduction pages that are accessible

A number of sites had introduction pages as the entrance to the job

application process that were inaccessible to screen-reader users and had

no textual equivalents. For instance, a few Web sites had a flash-based

job search page, without any textual equivalents. There was no way to

search for a job unless you could see the screen and could use a mouse

pointer. For example, a Web site required users to click on a map to

choose which region/country you wanted to apply for a job on, and then if

you chose the US, you were then required to choose a state (see Figure 3).

There were no textual equivalents for choosing the job region or state,

although this would be easy to design accessibly, using a drop-down menu

list. These features may seem visually appealing, and they could stay on

the Web site, however, textual equivalents need to be added so that users

who cannot use pointing devices could also access the information. The key

problem with these features is that they are at the entry point of the

entire employment process, so that if you cannot utilize these features,

you cannot go any further in the application process. These entry points

essentially prevent blind users from applying for jobs at these companies.

Figure 3. Web site where the participants

must click on a map, and there is no textual equivalent for screen-reader

users or those unable to use a mouse pointer

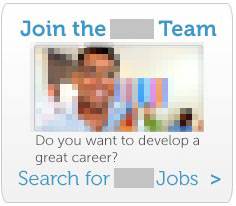

Provide accessible feedback on data entry problems

All online employment application processes

required users to fill out online forms, and this was expected. However,

there were instances on multiple sites where the feedback on data entry

forms was inaccessibly provided when data fields were filled out

incorrectly, as recorded in Table 1. Inaccessible methods for providing

feedback included highlighting the incorrectly filled-out field in red or

providing feedback only in an inaccessible mouse-over. On one employment

site (see Figure 4), the participants were prompted in a dialog box that

they should hover over the problematic data entry fields with their mouse

to learn what the problem is. A similar problem was noted on other Web

sites, (e.g., see Figure 5) where the participants were given information

about the data entry problem only through the use of a mouse-over on

fields that were marked with a red exclamation point.

Figure 4. Feedback on a Web site about an

incorrectly filled-out data entry form was provided in an inaccessible

manner. The dialog box notes that, to find out what the error was, the

participant should hover over the field with their mouse.

Figure 5. Feedback on the data entry from a

Web site was provided only by doing a mouse-over where a red exclamation

point was indicated as a field with incorrect data entry.

Provide accessible feedback regarding participant progress through the application

Typically, there are a number of steps that an applicant must complete

before they can formally submit an application. Unlike e-commerce sites,

where there is a standard and simple process (place items in the shopping

cart, and then go to the checkout), submitting a job application is a much

longer process, requiring as many as 10 different steps, and the actual

steps vary widely from site to site. Unfortunately, the status feedback on

participant progress through the sites we tested tended to be

inaccessible, that is, the feedback was provided only graphically, through

the use of shading, shapes, or colors, rather than a simple textual

declaration saying “you have completed step 3 (previous employment) out of

9 steps” or something similar. Because the steps varied so widely from

site to site, it was unrealistic to expect participants to know how many

steps were involved or which steps were involved. Figure 6 displays

progress indicators from three different sites, which show the various

steps in the job application process, but show the data in an inaccessible

manner.

Figure 6. Progress indicators from different

Web sites, which show the progress in an inaccessible manner that is

unusable to screen-reader users

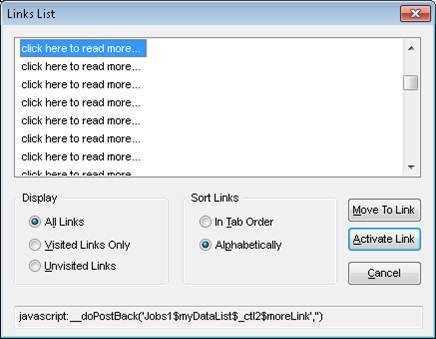

Use links that are unique and identifiable when listened to using a

screen reader

A number of Web sites had link text that was listed

as “click here” or “click here to read more.” When a screen reader user

listens to these links using the JAWS links list feature, all of the links

sound exactly alike and are identical and not individually identifiable.

This is easy to fix, instead of having all links read “click here,”

developers should designate the actual job titles as the links. On one of

the Web sites, all of the job listings had links titled “more info,” and

on another Web site, all of the job listings had links titled “click here

to read more” (see Figure 7). The outcome of that design decision is

presented in Figure 8, where the JAWS links list displays a list of links,

and the participant therefore hears a list of links titled “click here to

read more.”

Figure 7. A list of job links that all have the same text: “click here to read more”

which would be meaningless to screen-reader users

Figure 8. The JAWS links list on a Web site

job listing, where all jobs have the same link title, which was confusing

and meaningless to screen-reader participants

Use appropriate markup for lists and groups of questions

Users of screen readers rely on the Web design code (such as HTML) to

provide appropriate information about the structure of information

presented on the screen. For instance, headers (such as H1, H2, H3)

provide information about the meaningful headings on the Web page, which

allow users to navigate through those headings. Rather than presenting

content with the goal of how it will appear visually, it is important to

provide content with the goal of coding to indicate meaning and structure.

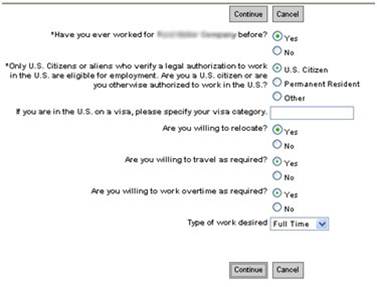

Figure 9 provides an example of a problem where the participants are not

hearing the questions and the answers together, but are hearing all of the

seven questions listed together, and then the answers are read together.

Developers sometimes use tables for visual layout, and this can confuse

screen-reader users who count on structured Web design code to understand

the meaning and relationship between items on the Web page.

Figure 9. Example where participants were not hearing the questions and the answers

read together, but were hearing all of the questions first, and then all of the answers.

Common Problems Related to General Usability

Participants in this study faced a number of

problems that were not specific to blind participants, but rather were

general problems with usability that would apply to all users.

Data is required that does not make logical sense

There were a number of sites where the required data fields were noted by

using red stars (which, itself, might be a problem for blind users if

there are no non-visual equivalents for indicating a required field).

However, in some cases, the required fields simply did not make sense. For

instance, in Figure 10, the start date and end date of a job were

required, which makes sense generally, even though there was an option to

note that a job was the current job. Even if the check box for current job

was selected, the participant still needed to provide an end date, even if

there was no end date. This clearly could be confusing to users.

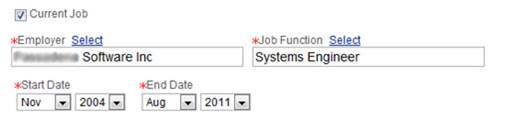

Figure 10. Participants were required to

enter an end date for their current job, which makes no logical sense.

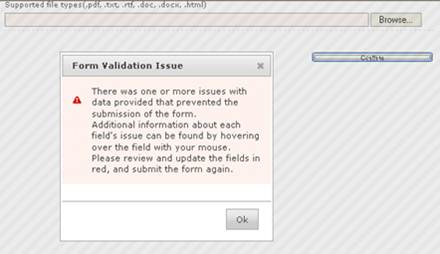

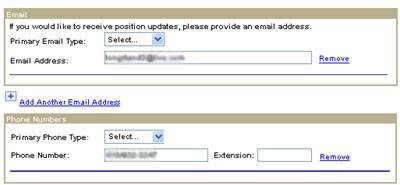

Data fields are required, but users are not informed that the fields

are required

If a data field is required, that needs to be stated clearly. The lack of this

type of information to the user was obvious, as shown Table 1. It is

understandable that there are data fields that must be required, such as

for name, contact information (such as email and phone), and educational

degrees. However, if these fields are required, that fact needs to be

clearly communicated to all users. Typically, the wording “Required field”

should be used, or if a red star or something is used to indicate a

required field, there should be equivalents (such as alt text) that

indicate for color-blind, low-vision, or blind users that the field is

required. In Figure 11, there are no indications that both email and phone

numbers are required fields. Yet if the data is not entered in those

fields, users will receive an error message.

Figure 11. Required data entry fields with

no indication (to blind participants or any users) that the fields are

required

Participants are required to do a “lookup” when a data field is more

suited to free text

When there are a limited number of potential

choices in a data entry field, a drop-down list makes sense. However, when

there are potentially thousands of possible choices, participants should

simply be allowed to use free-text entry to indicate their data. Yet one

of the online employment applications required that participants search

for and select the colleges and universities that they attended. This is

not standard on most online employment applications. Participants were

required to enter the title of their school and then select from a list of

potential matches to their search string. This approach was especially

problematic when either a school was listed multiple times for the same

school, or when there was a university system with multiple campuses with

similar names. In the example in Figure 12, multiple campuses of a

university were listed, and the same campus was listed more than once.

Figure 12. Multiple campuses of a university

were listed, and the same campus was listed more than once, which was

confusing to all users.

Participants in the study attempting to apply for

jobs tended to find this approach problematic and confusing. It would be

understandable if the choice from a list was required because it would

note a specific code for a university, and then allow access for the

employer to student records and transcripts from potential employees;

however, at no point in the application process were participants asked to

give permission to access transcripts, so this cannot be connected to

providing the university name.

Data entry is required in a specific format, but the format desired is

unclear

Earlier in this paper, the problem of inaccessible feedback on data entry

was discussed. Another related problem is the problem of unclear guidance

on what format data should be entered in, where, even though the feedback

is accessible, it still is not meaningful for any users (refer to the data

in Table 1). For instance, in Figure 13, the data entry field was supposed

to be entered in a currency format ($XXX.XX), but the field itself did not

clearly indicate that, and the error message in Figure 13 did not in any

way specify how participants should enter the data, only that the data was

entered improperly.

Figure 13. Unclear error message related to

data field entry, which is confusing to all users

Users are not given the opportunity to indicate that more time is

needed

In five of the participant attempts to submit a job application, the

application automatically timed out because the participant had reached a

certain time limit, without notifying the participant or giving the

participant the opportunity to indicate that more time was needed. This

impacts usability for users who may be busy (and may have their

application task interrupted by other pressing tasks) and novice users of

assistive technologies, who may need more time to complete an application

task.

Recommendations

There were a number of usability problems on the

employment application Web sites that were problematic for the blind

participants in this usability study and kept the participants from

independently submitting applications online. However, none of these

usability problems were ones that were technically hard to solve or

address. These were all commonly-known and understood problems, relating

both to accessibility for blind users and general usability for all users.

The solutions themselves are easy—such as creating textual equivalents for

clickable image maps, accessible feedback for form errors, and clearly

stating which fields are required and which data format should be used.

For instance, if any of these employment application Web sites followed

either Section 508 (Section508.gov, 1998) or the Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines (W3C, 2011b), it is likely that most of the accessibility

problems mentioned previously in the paper would have been addressed.

Companies should ensure that their online employment processes are

accessible and usable for users with disabilities.

If online employment application software is being

purchased (such as solutions from Kenexa or Taleo) employers should

request documentation that the software complies with Section 508, similar

laws in other countries, or international standards. This can be done by

asking for documentation of what methods were used to check for

accessibility, or asking for a Voluntary Product Accessibility Template®

(VPAT®) that documents the accessibility features (http://www.itic.org/index.php?src=gendocs&ref=vpat&category=resources).

While it is possible that users with disabilities would face challenges in

using the interface that are not covered under Section 508, the most basic

accessibility problems documented in this study would have indeed been

covered under Section 508 or similar laws.

If online employment application software is being

developed or modified in-house, good user-centered design techniques

should be used to ensure accessibility. These techniques include usability

testing involving people with disabilities, expert inspections using

assistive technology, and automated accessibility testing (software such

as HiSoftware Compliance Sheriff, Odellus ComplyFirst, and Deque

Worldspace). In addition, if the online employment process Web pages are

going to be modified in any way, accessibility needs to be considered in

the modifications.

Even though there is additional expense and time

involved with user testing, we believe that it is important to have real

users with disabilities test Web sites. We uncovered the following

usability problems that would likely not be detected by automated software

tools:

- Many of the usability challenges we

consider to be serious for the blind participants in our study, such as no

clear identification of when fields are required fields, free-text being

preferred to look-up, and unclear data format preference, would definitely

not be detected. - While it’s likely that the inaccessible

maps with no textual equivalent would be flagged, it’s unlikely that the

inaccessible feedback when users entered incorrect information would be

detected. - User actions, such as entering incorrect

information, were required before the inaccessible feedback was triggered.

Without the actions, the feedback would not be evaluated. - Data fields that do not make logical sense,

such as requiring an “end date” to a job those participants marked as

their current job, would not be detected.

Automated accessibility testing tools are necessary

for evaluating and monitoring any large Web site, as there may be

thousands of sub-sites and pages; however, those tools are not a

replacement for user testing, especially when users with disabilities must

perform tasks that involve a series of sub-tasks across multiple screens.

User-based testing provides a much deeper understanding of accessibility

and usability.

It is important to note that these participant

attempts to submit applications were only the first step in the process of

applying for a job. The entire process, once the individual submits the

application, must also be accessible. If these applications were real

applications (and not marked with “for training purposes only”), and if

these applicants were chosen for interviews and further review, those

future steps would also need to be accessible. For instance, there are

reports of many employers requiring potential employees to take online

aptitude tests. Are these online tests accessible? Are follow-up

communications electronic? If so, are they accessible? And furthermore

(and non-technically), when potential employees go for an interview, are

those face-to-face meetings in accessible locations? Do the offices and

buildings have Braille signage? This usability evaluation has only

examined the initial attempts to submit an employment application online.

Future work needs to evaluate the accessibility of the entire process.

Conclusion

This study examined the accessibility and usability

of 16 employer Web sites in the southeastern United States, and it

revealed that the majority of attempts by blind individuals to apply for

jobs using these Web sites were not successful. There were many unique

problems identified (see Table 1). Accessibility and broader usability

challenges can clearly prevent or discourage users with disabilities from

even the earliest phases of the process of seeking and obtaining

employment, as illustrated in this study. When a particular segment of the

population (e.g., people with disabilities) is in this manner prevented

from the right to apply for employment, it amounts to discrimination.

Accessible and usable online employment applications should be a priority

for employers, and the negative impact that this has on people with

disabilities must be understood. As illustrated in this research, most of

the problems related to electronic accessibility and usability are easy

for designers to correct. Following guidelines such as Section 508 and

WCAG can allow businesses to make significant progress towards providing

equal opportunities for all individuals to gain employment.

References

- Braddy, P., Meade, A., & Kroustalis, C. (2008). Online recruiting: The effects of organizational familiarity, website

usability, and website attractiveness on viewers’ impressions of organizations. Computers in Human Behavior 24(6): 2992, 2993. - Breen, B. (2000). Full house. Fast Company. Retrieved March 22, 2011 from http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/42/pp_bellagio.html?page=0%2C0

- Bruyere, S., Erickson, E., & VanLooy, S. (2005). Information technology and the workplace: Implications for persons with

disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly25(2). Available at

http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/548/725 - Bureau of Labor Statistics (2011, November). The employment situation. Retrieved December 14, 2011 from

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_12022011.htm - Canadian Federation of the Blind (2011). Review:

The politics of blindness: From charity to parity. Retrieved December 14,

2011 from

http://www.cfb.ca/review-the-politics-of-blindness-from-charity-to-parity - Capellli, P. (2001). Making the most of online

recruiting. Harvard Business Review,

Harvard Business Publishing. 79(3), 139–146. - Department of Justice (2010). Nondiscrimination on

the basis of disability; Accessibility of web information and services of

state and local government entities and public accommodations. Retrieved

December 15, 2011 from

http://www.ada.gov/anprm2010/web%20anprm_2010.htm - Department of Labor (2011). Affirmative action and

nondiscrimination obligations of contractors and subcontractors:

Evaluation of recruitment and placement results under Section 503.

Retrieved December 15, 2011 from

http://www.dol.gov/ofccp/regs/unifiedagenda/Spring-2011/1250-AA02.htm - Everett, C. (2011). Online recruitment sites “not

accessible.” Retrieved March 13, 2011 from

http://www.hrzone.co.uk/topic/recruitment/online-recruitment-sites-not-accessible/109886 - Frey, B. (2008). Happiness research in economics—A

revolution? Journal of Happiness

Studies, 10(4), 499-502. - Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists

learn from happiness research?

Journal of Economic Literature

40(2), 402–435. - Hastings, R. (2010). Making recruiting sites

accessible for all. Retrieved May 5, 2011 from

http://www.shrm.org/hrdisciplines/Diversity/Articles/Pages/RecruitingSitesAccessible.aspx - Lazar, J., Feng, J., & Allen, A. (2006).

Determining the impact of computer frustration on the mood of blind users

browsing the web. Proceedings of ACM

Conference on Assistive Technology (ASSETS; pp. 149-156). Portland,

OR, USA: ACM (New York, USA). - Lazar, J., Wentz, B., Biggers, D., Delair, J.,

Donnelly, M., Kashim, E., Henin, A., Markakis, J., Matos, A., McNicol, A.,

Nixon, J., Osborne, R., Postnova, T., Raja, J., Roberts, R., Serra, H.,

Sfakianoudis, V., Tyler, V., & Yun, J. (2011). Societal inclusion:

Evaluating the accessibility of job placement and travel web sites.

Proceedings of the INCLUDE 2011

conference, London, UK, Royal College of Art., Available at

http://www.hhc.rca.ac.uk/3845/all/1/proceedings.aspx - Meskauskas, J. (2003). The potential of online job

boards. iMedia Connections. Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.imediaconnection.com/content/2013.imc - Nakamura, A., Shaw, K., Freeman, R., Nakamura, E.,

& Pyman, A. (2009). Jobs online. In: Autor, D.H. (Ed.)

Studies of Labor Market Intermediation (National Bureau of Economic

Research Conference, May 17-18, 2007; pp. 27 – 66). The University of

Chicago Press. - National Federation of the Blind (2010). Senators

Dodd and McCain introduce Blind Persons Return to Work Act: National

Federation of the Blind applauds a common sense work incentive for blind

social security beneficiaries. Retrieved March 9, 2011 from

http://www.nfb.org/nfb/NewsBot.asp?MODE=VIEW&ID=547 - National Federation of the Blind (2011). NFB

executive Mark Riccobono honored by Wisconsin Alumni Association.

Retrieved December 14, 2011 from

http://www.nfb.org/NewsBot.asp?MODE=VIEW&ID=769 - Office for National Statistics (2011, November).

Labor market statistics. Retrieved December 14, 2011 from

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/lms/labour-market-statistics/december-2011/index.html - Olalere, A., & Lazar, J. (2011). Accessibility of

U.S. Federal Government home pages: Section 508 compliance and site

accessibility statements. Government

Information Quarterly 28(3),

303-309. - Ross, T. (2011, January 10). Happiness is having a

job, and the salary doesn’t matter.

The Telegraph, Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/science-news/8249538/Happiness-is-having-a-job-and-the-salary-doesnt-matter.html - Royal National Institute of Blind People (2011a).

Key information and statistics. Retrieved March 14, 2011 from

http://www.rnib.org.uk/aboutus/Research/statistics/Pages/statistics.aspx - Royal National Institute of Blind People (2011b).

UK law for websites. Does the law require me to make my site accessible?

Retrieved March 14, 2011 from

http://www.rnib.org.uk/professionals/webaccessibility/lawsandstandards/Pages/uk_law.aspx - Section508.gov (1998). Section 508 of the

Rehabilitation Act. Available at

http://section508.gov/index.cfm?fuseAction=1998Amend - Statistics Canada (2011, November). Labor force

survey. Retrieved December 14, 2011 from

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/subjects-sujets/labour-travail/lfs-epa/lfs-epa-eng.pdf - Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2007). Common

look and feel standards for the Internet, part 3: Standard on common web

page formats. Retrieved March 14, 2011 from

http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/clf2-nsi2/clfs-nnsi/clfs-nnsi-3-eng.asp - W3C (2011a). Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI).

Retrieved March 23, 2011 from http://www.w3.org/WAI/ - W3C (2011b). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

(WCAG). Retrieved March 23, 2011 from

http://www.w3.org/WAI/intro/wcag - Wang, K., Barron, L., & Hebl, M. (2010). Making

those who cannot see look best: Effects of visual resume formatting on

ratings of job applicants with blindness.

Rehabilitation Psychology,

55(1), 68-73. - WebAIM (2010). Screen reader user survey #3

results. Retrieved February 2, 2012 from

http://webaim.org/projects/screenreadersurvey3/ - Wentz, B., & Lazar, J. (2011). Usability evaluation

of email applications by blind users.

Journal of Usability Studies,

6(2), 75-89. - Williams, S., & Verhoeven, H. (2008). “We-find-you”

or “You-find-us”? – Internet recruitment and selection in the United

Kingdom. International Review of

Business Research Papers, 4(1),

374-384. - Younger, J. (2008). Online job recruitment: Trends,

benefits, outcomes, and implications.

International Review of Business

Research Papers, 4(1),

374-383.