Abstract

This paper examines the use of physical persuasive cards for novice designers in ideation sessions. Through experimental study, we found that the tools a designer uses affects the kind of outcome they will get. The observations from four workshop sessions indicate that persuasive cards can be a two-edged sword, as they can affect the design process both positively and negatively.

Additionally, in this paper, certain insights are highlighted when it came to how novice designers interacted with the cards. One of the most interesting behaviors witnessed was how participants were depending on the cards while debating their own ideas, and in some situations, neglecting their own or their colleagues’ ideas as they believed the cards knew better.

Moreover, this study was able to report “The Commonality Effect” as a new finding, as session outcomes from with-card teams showed a higher rate of repetitiveness and commonality in the persuasive ideas.

This paper provides 10 design card heuristics that can be used as a guideline when it comes to producing and evaluating card-based tools.

Keywords

User centered design, human-computer interaction, design activity, creativity, card-based tool, Persuasive principles, Persuasive design, idea generation

Introduction

Physical design cards have been around for a long time, and “have been complimented to be more affordable in the creative process than other means of tools” (Ren et al., 2017, p. 454). Numerous card-sets have been developed to facilitate ideation, inspiration, and participatory design. Many studies have stated that the main advantage of design cards is that they work as intermediate-level knowledge “to communicate research insights and make them usable in a design process” (Chung & Liang, 2015, p. 3), because “theoretical frameworks often are high level and only abstractly inform design processes” (Hornecker, 2010, p. 108). Therefore, there have been many efforts to introduce a different set of cards to serve as intermediate-level knowledge that bridge between theories and practice. One example of these are persuasive cards based on different persuasive theoretical approaches such as the Persuasive Systems Design (PSD) model, cognitive biases, and other psychological concepts.

However, one limitation of previous studies in design cards is that “most researchers could not clearly claim what the significance of their design of a tool is” (Chung & Liang, 2015, p. 3), which is an area that this study is trying to contribute to through exploring whether persuasive cards benefit or hinder persuasive technology design processes. As it is beneficial for designers to become familiar with the strengths and limitations of persuasive card-based tools before using or creating one. Another gap in previous studies, which this study is trying to fill, is that “cards are usually tested and applied by their developers, so more independent trials are needed to establish their effectiveness” (Roy & Warren, 2019, p. 125). Therefore, this experimental study is presenting itself as an independent experimental test to evaluate the use of such a tool focusing on one type of users: novice designers.

The aim of this study is to contribute to the discussion within the HCI community and literature on the topic of using persuasive cards in the design process. This is done by investigating whether their usage in ideation sessions can influence the design process positively or negatively for novice designers, as well as using the insights gathered to create design card heuristics to help users in the evaluation or creation of more effective design cards.

The research question can be stated as the following:

To what extent do persuasive design cards influence the ideation of persuasive design for novice designers?

For the scope of this project, the focus was specifically investigating the extent to which physical persuasive card-based tools support or hinder the design process for novice designers only. The duration of use was not a focus in this research; due to time limitations, only one-session card usage for each design team was researched and is presented in this paper. Also, we did not look at how participants presented their persuasive ideas, as the focus was on the ideas themselves not the form they were represented in.

Literature Review

The following sections provide the context for the project, starting with a look at the difference between novice and expert designers, before providing an explanation of what persuasive cards are. Then, we explore related works in design card usage.

Novice Designers

“Novice and experienced designers differ in how they approach design tasks” (Christiaans, 1992, p. 102), and “experienced designers tend to have a broad repertoire of design strategies and can flexibly combine multiple ones, whereas novice designers are less aware of the strategies” (Ahmed et al., 2003, p. 1). This implies that the differences in expertise could influence which techniques and tools designers use and how they use them. Therefore, this research chose to investigate the use of persuasive cards for novice designers, because the effect of the cards on them would be clearer as they lack the practical expertise. While for experts, it would be harder to distinguish whether the approach they followed comes from the cards or from the designer’s expertise.

Persuasive Technology

“Persuasive Technology is the study about computing technology designed to change people’s attitudes and behaviors” (Ren et al., 2017, p. 453). A lot of theoretical work has been done to present persuasive models and principles, and attitudinal theories from social psychology have been quite extensively applied as a persuasive framework.

The best-known example is the Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) for Persuasive Design developed by Fogg (2009). Based on Fogg’s work, Oinas-Kukkonen and Harjumaa (2009) conceptualized the PSD model that establishes four categories of 28 persuasive design principles “partly derived from Fogg’s theory,” and they are widely used to design persuasive technology.

Related Work

On one hand, in addition to their direct role in ideas inspiration, “design cards can also help kick off design discussion and foster focus shift when the discussion becomes unproductive” (Deng et al., 2014). Also, Bekker and Antle (2011) discussed the advantages of card decks as a design tool: “Cards are small which means that information must be presented simply and concisely. Their form enables a variety of uses, reuse, and supports a flexible hands-on approach to bringing conceptual information into design” (p. 2532).

On the other hand, research found some weaknesses that physical card-based tools are a “static format, which may suffer from lack of updateability, and they are time consuming. In addition, the card set format can oversimplify important information” (Casais et al., 2016, p. 4).

While for the use of persuasive design cards specifically, there is only one attempt by Ren et al. (2017) who developed Perswedo, which is a card deck that introduces persuasive principles from PSD, to support the creative design flow. They assessed the usefulness and value of Perswedo in the design process as well as the design implications of the cards through three design workshops in three different universities. All participants were from an interaction design program or senior bachelor students who studied interaction design for one year as electives. Their findings suggest that persuasive cards can inform the design process, and they were useful in ideation and different activities.

Before going any further, it should be mentioned that although research exists that does find design cards an effective design and inspiration tool, there is still a lot to be done. This study investigates in more depth the use of persuasive cards, and as the previous study that was done by the card developers themselves, this study is presenting itself as an independent experimental test.

Methods

This work follows a deductive research strategy by running a set of workshop sessions that aim to collect and analyze data on the topic of persuasive ideas generated as a result of using persuasive cards. The sessions described here took an experimental approach using the same design task, persona, and location in all the workshop sessions.

This experimental test followed a between-subjects structure to avoid bias and learning effects. Therefore, it was important to recruit participants who have similar backgrounds and expertise. The conducted workshop contained four sessions: two with-card sessions where the card deck was provided for participants to use and the other two without-card sessions where the card deck was not presented.

This study focused primarily on qualitative data more than quantitative data collected through short-term observation sessions because “quantitative metrics of product quality or creativity are difficult to apply, observation and interaction with creative individuals and groups over weeks or months are necessary” (Shneiderman et al., 2006, p. 69). Also, each session was followed by questionnaires and focus group discussions as “these research methods can be made more rigorous by applying standard yet focused interview and survey questions across a range of individuals” (Shneiderman et al., 2006, p. 69).

Participants

This experimental study recruited 12 participants (two sample sizes of six) divided into four sessions, and each session contained a team of three participants. This is because having more than three participants in one team could make the brainstorming sessions longer in time and require introducing some rules, such as turn-based contribution, which may affect the natural flow of teamwork. As a result, three participants were a convenient number for a team.

This study followed a rigorous procedure and recruiting criteria:

- A strict set of user characteristics was followed as all participants were

- 2018/2019 full-time HCI Design students from City University of London,

- carried out a lot of ideation sessions, and

- none of them had used cards to ideate in the past.

- None of the participants had seen or used the tested website before.

- All sessions had the same task, website, persona, procedure, and amount of time.

- All sessions were carried out in the same location, the university’s City Interaction lab.

Recruiting participants was done via social media to ensure that we could reach a large audience, as well as by email sent out within City University of London students.

Design Task and Persona

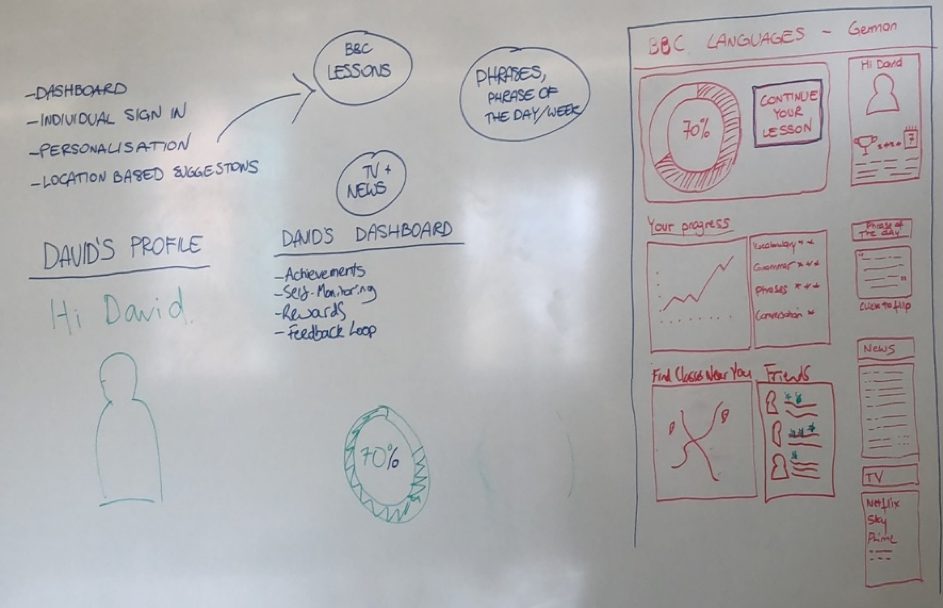

The researcher developed a design problem that involved asking participants to make the BBC Languages German webpage more persuasive by suggesting persuasive features/ideas to add them to the website (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The design task.

The researcher chose this website for the following reasons:

- The chances of the participants having previously used the website is very low, as it is an archived page.

- It is only a one-page site that is suitable for a one-session ideation. Having a bigger website would have complicated the task and would have required more time from participants to evaluate and come up with persuasive ideas.

- It is a static website and does not follow any persuasive techniques or have any persuasive features, which is suitable to avoid any chances of influencing the participants ideas.

Due to time constraints, we did not include a design case for evaluating the existing design. Although to be able to recommend persuasive features to a website, participants need to evaluate the existing design. Instead, we provided a small introduction to the website and its features to save time. Also, we asked participants to represent their persuasive ideas in any way they preferred, as the goal was to compare the persuasive features/ideas between all sessions and not the form participants chose to present them in.

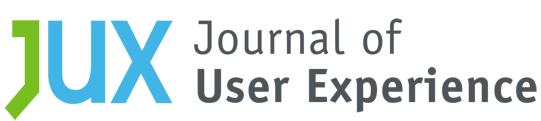

To make the task manageable in a 1 ½ hour session, we created a simple persona. This allowed participants to engage in the ideation sessions faster and save time and to make all sessions’ outcomes revolve around the same aim and understanding of the design space. Figure 2 shows the persona.

Figure 2. The persona.

Questionnaires and Focus Group

This research used two types of questionnaire: Creativity Support Index (CSI) questionnaire and the Single Ease and Satisfaction Rate questionnaire.

Creativity Support Index (CSI) Questionnaire

Developed by Cherry and Latulipe (2014), CSI is a psychometric survey designed for evaluating the ability of a creativity support tool to assist a user engaged in creative work. The CSI allows researchers to understand not just how well a tool supports creative work overall, but what aspects of creativity support may need attention. A paper version of this questionnaire with an open-question section at the end was used only in with-card sessions to allow the participants to rate the persuasive cards after using them.

Even though, Cherry and Latulipe (2014) recommended that researchers administer the CSI using the application that they developed; they stated, “It is entirely possible to administer the CSI on paper” (Cherry & Latulipe, 2014, p. 7) which was a convenient option for this study as we had very limited lab-time and only one computer. Therefore, CSI in paper form helped us to let all participants complete the questionnaire at the same time and then move on to the focus group discussion without wasting time.

Single Ease and Satisfaction Rate Questionnaire

This questionnaire, with an open-question section at the end, was used in both with-card and without-card sessions. The aim was to collect and compare how easy or difficult it was to generate persuasive features/ideas with and without using persuasive cards. An additional aim was to collect and compare participant satisfaction rates for all sessions.

Holding a focus group seemed to be a suitable way of gathering more data on the subject as “the benefit of a focus group is that it allows diverse or sensitive issues to be raised that might otherwise be missed” (Rogers et al., 2015, p. 338). The aim was to give participants the chance to discuss their thoughts and experiences and debate their opinions in a 15-minute discussion. Using focus groups as a method to open the conversation between participants maximized the opportunity for the collection of rich data that would give rise to the identification of a wide range of qualitative data.

Please see Appendix A for a copy of the questionnaires.

Materials

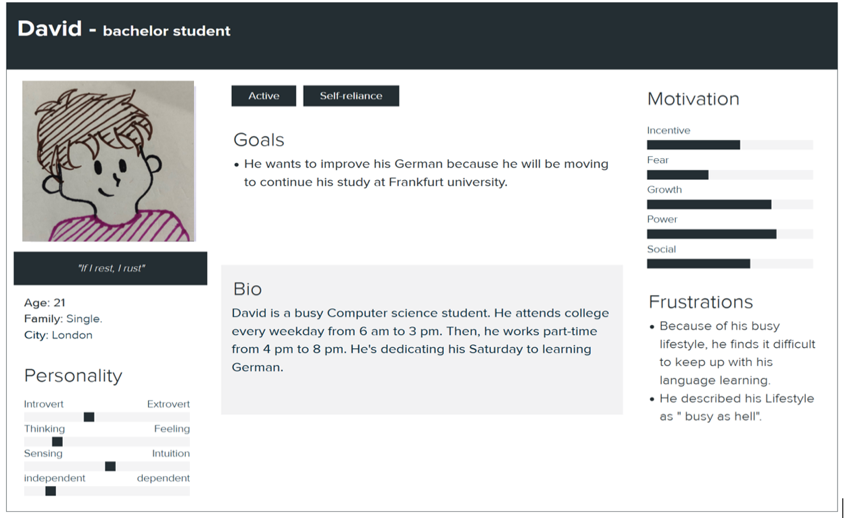

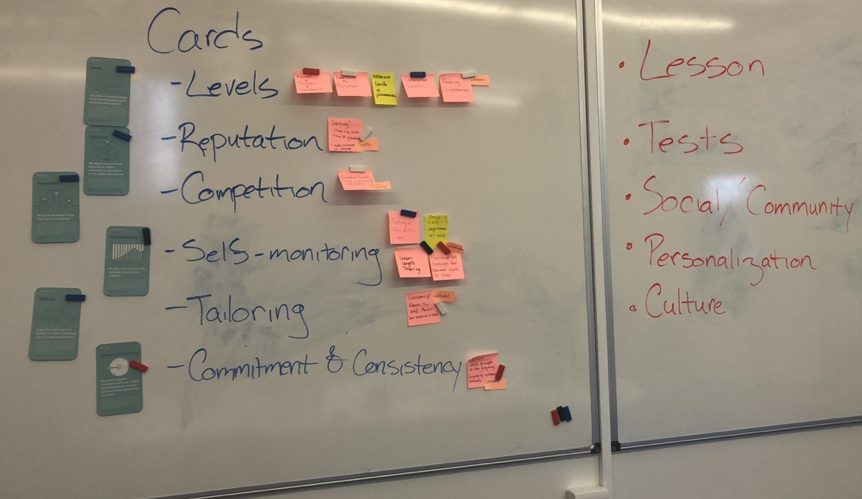

Before deciding which persuasive card-deck would be used in this project, we examined and compared the available choices. The result of comparing was that persuasive cards, unlike other inspirational design cards, provide the same principles from psychological persuasive theories and other principles that are widely used in the HCI field. For example, the Perswedo deck developed by Ren et al. (2017) provides persuasive principles from PSD model which contains four categories of 28 persuasive principles developed by Oinas-Kukkonen and Harjumaa (2009). Therefore, the chosen card-deck in this study present the same 28 persuasive principles provided in Perswedo and goes beyond that to provide more psychological insights in 60 cards. The chosen card-deck name is Persuasive pattern from UI-Patterns.com.

Figure 3 is an example of the persuasive pattern cards used in the study.

Figure 3. One of the persuasive pattern cards.

The other test materials and equipment that were prepared are as follows:

- whiteboard, paper, Post-it notes, pens and sharpies, and so on

- recording equipment (video and audio recording by a camera)

- laptop with internet connection (to allow participants to examine the website)

- paperwork (consent forms and participants information sheets)

Also, we prepared a script that “ensures that each participant will be treated in exactly the same way, which brings more credibility to the results obtained from the study” (Rogers et al., 2015, p. 368). Finally, before evaluating the persuasive cards with users, a pilot study was undertaken “to determine the reliability of the test procedures and to detect any potential practical problems” (Rogers et al., 2015, p. 328).

Workshop Procedure

All sessions were essentially identical in the number of subjects, location, task, and persona, except for the warm-up phase, where with-card sessions got 15 minutes instead of 10 minutes to allow the participants to explore the card-deck and familiarize themselves with it.

Table 1 presents each session, which consisted of six phases.

Table 1. Sessions Structure

|

Phase |

Purpose |

|

5-minute instruction |

Complete consent forms and provide the workshop guidelines. |

|

For without-card sessions, 10-minute warm-up For with-card sessions, 15-minute warm-up |

Present the design problem and persona and also explore the cards for the with-card session. |

|

50-minute ideation |

Brainstorm with or without cards. |

|

5-minute presentation |

Participants present what they came up with. |

|

5-minute questionnaires |

Complete the questionnaires individually. |

|

15-minute focus group |

Run a focus group discussion between the participants. |

The purpose of the instruction section was to ask subjects to read and complete the consent form and to allow them to ask the researcher anything. Before that, the participants were provided with a short description of the purpose of the study through a script, and they were presented with the participant information sheet. It was important at this point to reassure them that all of the details of this study remain confidential and that they can withdraw from the study at any point.

The purpose of the warm-up section was to give the participants a chance to explore and understand the design problem, analyze the persona, and get a feeling for the flow and functions of the workshop, as “sessions that started from a well understood problem or setting and had settled on core goals were most successful, while sessions unguided by initial constraints tended to lose focus” (Hornecker, 2010, p. 6).

The ideating phase consisted of participants collaborating to solve the design problem and trying to generate persuasive ideas/features for the website. As previously mentioned, in without-cards sessions, participants generated their ideas without the cards. Whereas with-cards sessions, participants were using the cards that were spread out on the table around where they were seated. Figure 4 shows the with-card sessions setting.

Figure 4. With-card sessions setting. All sessions were conducted in the same room with the same setting except for the cards on the table in the without-card sessions.

There were no rules for turn-taking; participants were encouraged to discuss the cards, use the whiteboard and other materials, and add text or visuals to explain and refine their persuasive ideas. After that, the presentation phase started where the participants presented their persuasive outcomes and explained their rationale.

Finally, to analyze and interpret the collected data, we followed a thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006), as there was a large amount of raw qualitative data that the workshop produced. First, a transcription process was needed, so the recorded data were transcribed word by word and, in order to keep the subjects’ unidentifiable, all data was kept anonymous. This process was necessary “as it helped us gain familiarity with the data” (Makri et al., 2011, p. 12).

After the transcribing process was done, we categorized and listed all the persuasive outcomes of each session to make the comparison clearer and easier. Then, we used NVivo 12 software to analyze the transcript and denote any comments and statements the participants said, searched for themes, and then grouped the belonging comments to their themes.

Results

This section provides each sessions’ outcomes and provides an analysis of those results.

Sessions Outcomes

Session 1: In this session, the card-deck was presented for participants to use, and they chose 13 cards out of 60. Their final persuasive concept was to make the website more dynamic which would make it more persuasive. The following is a list of their persuasive features/ideas:

- Provide personalization through personalized suggestions and content.

- Provide data visualization through a time-based graph and progress-wheel by percentage.

- Give achievement trophies, such as badges to collect.

- Use leveling to turn all the language skills “reading, writing, grammar…etc.” into levels to keep users driven to complete all levels.

- Provide a word and phrase of the day.

- Encourage socialization by having a profile that shows their learning status and level, also a list of friends with their learning status profiles to build up competition.

- Provide rewards, such as unlocking new features.

- Suggest location-based activities near them using

Session 2: In this session, the card-deck was presented, and they chose six cards out of 60. Their final persuasive concept was to give users control over their own learning journey through personalization and tailoring. Their persuasive features/ideas were the following:

- Provide personalization by letting users customize the content on their dashboard.

- Provide data visualization that shows progress through a time-based graph.

- Give achievement trophies, such as badges to collect.

- Use leveling to turn all the language skills into levels to drive users to complete all levels.

- Provide a phrase or word of the day.

- Encourage socialization through listing top learners to create competition.

- Provide a timer to give users control and allow them to tailor the length of the lesson, so they can set a short lesson or long one depending on their situation.

- Give a quick quiz to test their German language skills from time to time.

- Keep a reminder board so users can set a list of goals for themselves that appear as notifications to keep them on track.

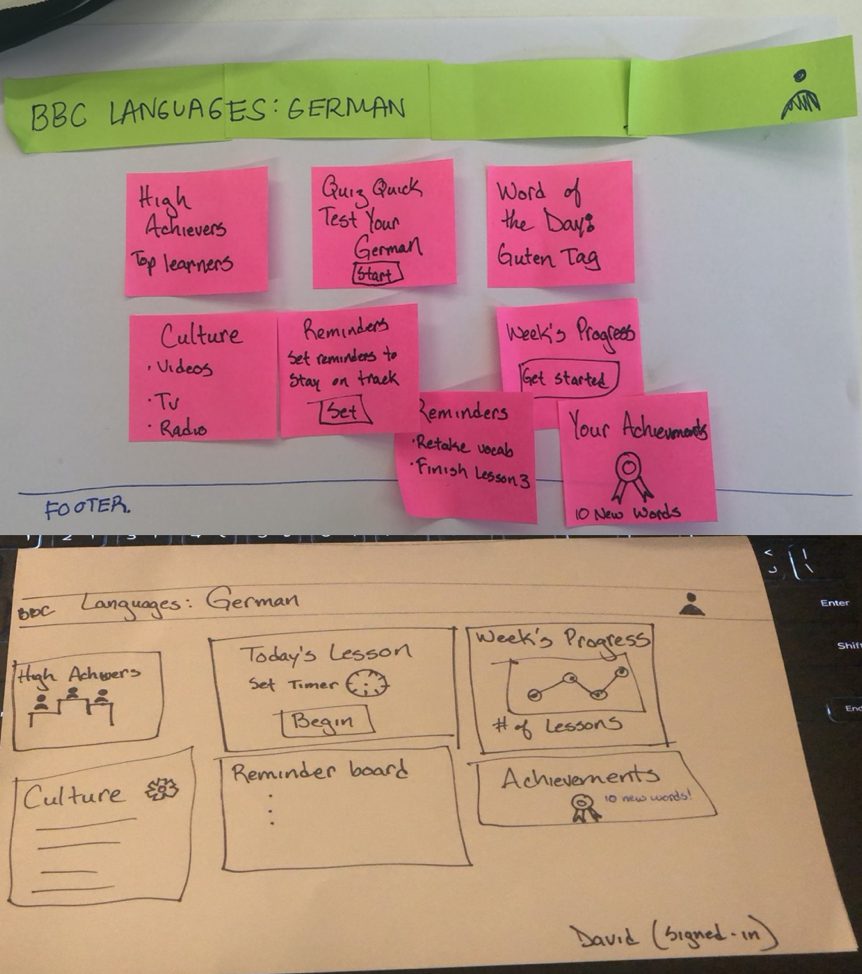

Session 3: In this session, the card-deck was absent. Their final persuasive concept was to give users specific personalized lessons based on a filter that they completed when first using the site. Their persuasive features/ideas were the following:

- Provide an accompanying mobile app that audibly provides information and notices so users can learn while commuting or exercising.

- Develop a webinar and Q & A sessions for virtual meetings to practice with your classmates.

- Provide online language 101 (beginner) courses.

- Encourage socialization through a social profile.

- Provide data visualization through time-base progress graph.

- Motivate by providing funny phrases to keep the learning fun and motivating, for example, “You have studied for about 600 minutes or 29 episodes of Friends!”

- Allow users to tailor the process themselves, such as allow users to create a list of lessons, small goals, or task-based skills.

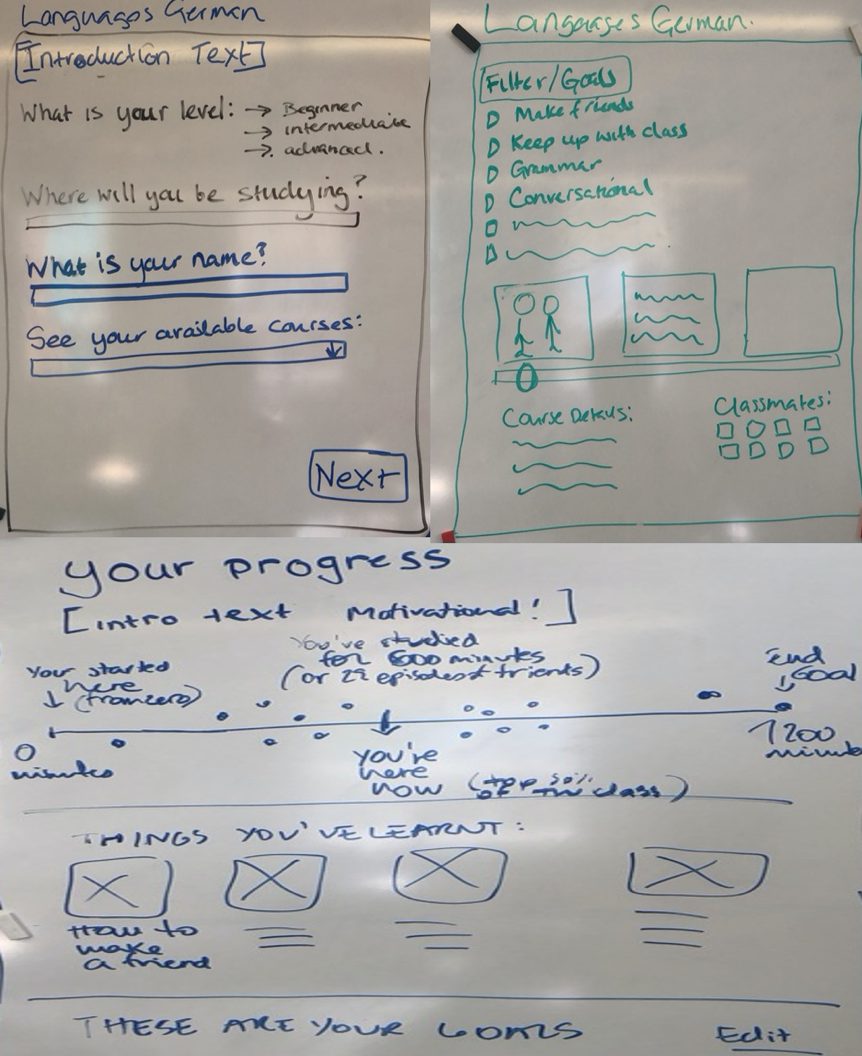

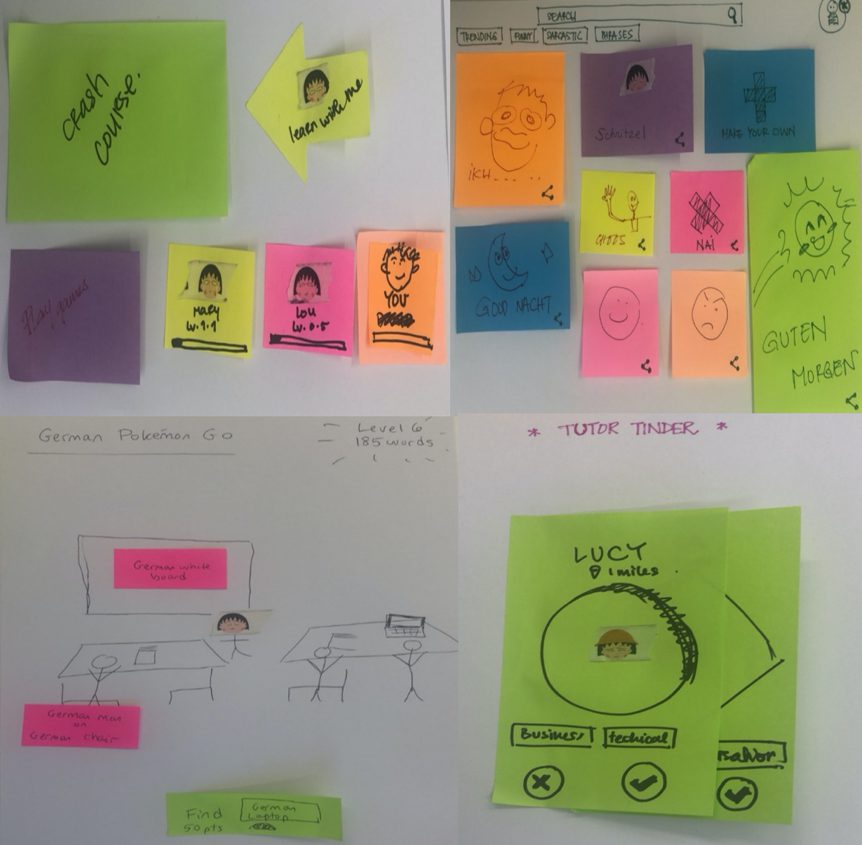

Session 4: In this session, the card-deck was absent. Their final persuasive concept was to make users learn the language in a very social way using gamification and social interaction. Their persuasive features/ideas were the following:

- Allow for creation of an animated avatar that will appear everywhere in the website to guide the user interactively.

- Provide for a crash course, such as educational games to teach users several German language lessons using flashcards as a challenge or to fill in the missing word.

- Provide a tutor “Tinder-like” app where users can find German teachers around their area to meet, with tags about the subject that they are lecturing about.

- Develop a German “Pokémon Go” like augmented reality game app that gives you a challenge to find objects around you by pointing your camera at the objects to “Catch Them All.” The objects to find will be presented to you in German such as “find a stuhl,” which means chair.

- Provide a way for people to create a “Your German Memes” page, where images and jokes in German will allow the community to interact and learn in a fun way. Each meme could come with an option to share it on a user wall or the ability to create their own memes. The more memes users share and create, the more points they gain until they become “Star-users.”

- Provide a weekly podcast show to download and listen to.

- Encourage socialization to allow users to have an avatar and show their gaining points and level on the wall of fame to compete and push them to progress. Also, use chats with other students as a way of learning.

Sessions’ Outcomes Analysis

After reading the abstracted list of persuasive ideas, we noticed that the number of ideas that the four teams came up with in the short time of the workshops was very similar: eight, nine, seven, and seven. Which means the cards did not cause a team to generate substantially more ideas.

However, a noticeable theme and commonality can be found among those in with-card session outcomes, while variations can be found in without-card sessions outcomes. By analyzing the lists from the with-card sessions, six of their persuasive features/ideas were shared between them. While only two persuasive features/ideas from without-card teams were shared with with-card teams, and only one idea was shared between without-card teams, as shown in in Table 2.

Table 2. Persuasive Ideas Comparison

|

Session 1 |

Session 2 |

Session 3 |

Session 4 |

|

(with-card) |

(without-card) |

||

|

Shared ideas |

|||

|

Socialization Data visualization Personalization Achievement trophies Leveling Phrase or word of the day |

Socialization Data visualization Personalization Achievement trophies Leveling Phrase or word of the day |

Socialization Data visualization |

Socialization |

|

Unshared ideas |

|||

|

Rewards Location based suggestions |

Timer Quiz, quick Reminder board |

Accompanied mobile app Webinar and Q & A sessions Online language 101 courses Funny phrases Tailor it yourself |

Animated avatar Crash Course Tutor tinder German Pokémon Go Your German memes page Weekly broadcast show |

Table 2 highlights an interesting pattern found in the persuasive features/ideas that came from the with-card sessions. Creating a commonality and repetitiveness in the ideas is something that cannot be found in the sessions that were structured without the cards. Looking at the list of selected cards and the number of the cards that were used in the two with-card sessions, it can be seen that the first team selected 13 cards out of 60, while the second team selected six. Interestingly, only four persuasive cards were shared as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Selected Cards List

|

Team: shared/unshared cards |

Cards |

|

Team 1 unshared cards |

Completion, Need for Closure, Powers, Rewards, Achievements, Status, Feedback Loops, Delighters, and Unlock Features |

|

The Shared cards |

Tailoring, Self-monitoring, Levels, and Competition |

|

Team 2 unshared cards |

Reputation and Commitment & Consistency |

Based on the with-card sessions transcript, both teams judged the cards based on the design problem and the persona presented, and they selected what they believed were relevant. Despite the differences in their judgement towards the unshared cards’ value and the number of cards they used, their persuasive outcome had some commonality to it. Table 4 shows both teams’ ideas and the cards they used as a source of inspiration.

Table 4. The Cards and the Ideas They Inspired

|

Team 1 |

Team 2 |

|

Personalization: through personalized suggestions and content. (Tailoring card) Data visualization: through a time-based graph and progress-wheel by percentage. (Self-monitoring card) Achievement trophies: give them badges to collect (Competition card – Achievement cards) Leveling: turn all the language skills “reading, writing, grammar…etc.” into levels to keep users driven to complete all levels (Levels card – Tailoring card) Word or phrase of the day (Tailoring card) Socialization: having a profile that shows their learning status and level, also a list-of-friends with their learning status profiles to build up competition (Competition card – status card) Rewards: unlock new features as a reward (Rewards card – unlock features – Delighters card) Location based suggestions: German activities near them by GPS (Delighters card) |

Personalization: users customize the content on their dashboard (Tailoring card) Data visualization: of week’s progress through time-based graph (Self-monitoring card) Achievement trophies: give them badges to collect (Competition card -Reputation card) Leveling: turn all the language skills into levels to drive users to complete all levels (Levels card – Tailoring card) Phrase or word of the day (Tailoring card) Socialization: through top learners list to create competition (Competition card – Reputation card) Timer: give users control and allow them to tailor the length of the lesson, so they can set a short lesson or long one depending on their situation (Tailoring card) Quiz, quick: test their German from time to time (Commitment & Consistency card) Reminder board: users can set a list of goals for themselves that appear as notification to keep them on track (Commitment & Consistency card) |

From Tables 3 and 4, we can see that the shared cards inspired both teams to suggest similar persuasive ideas/features, which indicates that there is a relationship between the shared cards and the common ideas of the with-card teams creating what is called in this paper “The Commonality Effect.” Such findings have not been reported before in previous studies.

The Commonality Effect

The results of the sessions indicate that there was a higher rate of repetitiveness and commonality in the persuasive ideas that came from with-card sessions, most of which were different from the ideas that the teams without cards came up with. Meaning that persuasive design cards influenced the outcomes for with-card teams.

This is a very interesting insight, as Tables 3 and 4 showed a relationship between the shared cards and the common ideas. Such correlation requires further study and more investigation for causation of the mechanism by which that could happen.

Important to clarify, this paper does not conclude that without-card teams did a better job of coming up with better persuasive ideas, as we did not even evaluate whether their ideas follow persuasive principles or not. We only report that they did not share as many ideas with with-card sessions, and they tackled the same design problem in a different way, which only suggests that the tools you use affect the kind of outcome that you will get.

Also, this paper does not specify that The Commonality Effect is a negative thing, as such an effect is a result of having shared cards, as if two teams used the same cards, you would expect them to come up with similar ideas. Therefore, the commonality is what the cards would produce as an intermediate level of knowledge. Rather, this commonality is an effect that any persuasive card user should be aware of so they can plan to go beyond repetitive and common ideas and move on to add uniqueness and personality to their brainstorming outcomes using persuasive cards as a source of inspiration. We suggest the following further actions:

- Have a follow-up brainstorming session without cards so the team can add their own originality to the ideas that came from using the cards. Or even better, make each ideation session have two to three rounds, and always discard the first round of ideas. The first round is for a warm-up, so you will always discard the result of the first round and only re-use the outcome of the second round onward. According to the result of the workshop, the first round will mostly generate obvious and common ideas.

- Set a rule for the team to not replicate existing ideas, examples, or suggestions that are written on the cards. Thus, assuring that the team would not repeat themselves.

- Mix and match ideas. It can be challenging to generate new ideas from the second and third round by mixing and matching cards. For example, when picking two random cards, it is the responsibility of the picker to attempt to come up with an idea that consists of the two cards. This approach might help a lot as teams often run out of obvious ideas after the first round and get stuck at the second and third rounds.

Participants Behavior with the Cards

From the notes taken during the observation sessions and the analyzed transcript, we noticed certain findings when it came to how participants interacted with the cards.

Firstly: FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) Behavior

In the beginning of the with-card sessions, participants scanned all the cards and agreed on certain cards to use as they were more relevant to the task, persona, and the goal they wanted to reach. However, during the rest of the session, they kept referring to the unused cards as a missed opportunity. Some participants kept going back and forth between what they picked as main cards to ideate and the rest of the deck. Regarding this, the following comment was said by one if the participants:

“I feel like they were useful but didn’t get the most out of them because I didn’t actually use all of them so I think I might have missed a potential very good card.”

Secondly: Over Reliance on the Cards May Limit Creativity

Another interesting behavior is that participants were depending on the cards while debating their own ideas and, in some situations, preferred to go with the card’s ideas and neglect their own or their colleagues’ ideas as they believed the cards knew better.

Thirdly: Number of the Cards in One Deck

Some participants thought that having 60 cards was overwhelming and not practical. Also, having that number of cards for a bigger team would bring some disadvantages, such as slowing the ideation process and making it harder for the team to agree on which persuasive cards they should use. One participant said:

“That number of cards is hard to physically remember them using our working memory, no one can consider them using the working memory.”

Fourthly: The Cards Visual Design

After the participants interacted with the cards and selected which ones they wanted to use, we asked them how they judged which card to pick up after scanning them all. All of them said that the title of the card is a vital piece of information that they can rely on.

However, the card design played the most important role here, and some participants could not read the text clearly as the description section font size was too small. This meant that they kept picking up the cards, bringing them closer to their faces, and then reading them, which is considerably more effort than if the text was slightly larger and could be read from the table without the need to pick them up to examine them.

Also, the color choices affected how they interacted with the cards as they could not differentiate between them, and they found the imagery totally irrelevant, stating it may have affected their choices. The following comments were said by some participants:

“[B]ecause the cards are all the same, the ones that have images and more white space popped out for me more and attracted me to pick them up.”

“The imagery is totally irrelevant and actually I found it distracting and possibly going to give me a bias because some are stunning some aren’t.”

Quantitative Data

Although the sample size in this study was small and therefore could not indicate any significant statistics, we preferred to report the quantitative data as directional insights so future studies could benefit from the suggested method and apply it to a bigger sample.

As stated before, the Creativity Support Index (CSI), developed by Cherry and Latulipe (2014), was used in this study. CSI is a psychometric survey designed for evaluating the ability of a creativity support tool to assist a user engaged in creative work.

The CSI measures six dimensions of creativity support: Exploration, Expressiveness, Immersion, Enjoyment, Results Worth Effort, and Collaboration. The CSI allows researchers to understand not just how well a tool supports creative work overall by giving it a single CSI score, but what aspects of creativity support may need attention.

CSI follows the American educational grading systems. A score above 90 is an “A” which indicates excellent support for creative work. A score below 50 is an “F” which indicates that the tool—or a specific individual factor—does not support creative work very well and needs more attention and work to improve it.

See Table 5 for a further break down of the average of these individual factors, rated by participants from the with-card sessions.

Table 5. CSI Individual Factors

|

Scale |

Avg. Factor Count |

Avg. Factor Score |

Avg. Weighted Factor Score |

Transformed Factor Score |

Grade |

|

Collaboration |

3 |

17 |

51 |

102 |

A |

|

Enjoyment |

1.3 |

16.2 |

21 |

42 |

F |

|

Exploration |

3.2 |

14.2 |

45 |

90 |

A |

|

Expressiveness |

3 |

16 |

48 |

96 |

A |

|

Immersion |

1.5 |

8.6 |

13 |

26 |

F |

|

Results Worth Effort |

3 |

16 |

48 |

96 |

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average |

|

|

|

75.3 |

|

As shown in Table 5, the exercise was successful with regard to Collaboration, Exploration, Expressiveness, and Results Worth Effort, but fell short with regard to Enjoyment and Immersion, indicating that they are not particularly important or less important to users when engaged in persuasive cards brainstorming sessions. Also, it means those two individual factors need more attention and improvement to score a success grade in CSI.

Another thing to note is that there are two contributors to a lower factor score: the ratings on the items that are averaged for that factor and its importance in the evaluation as indicated by the factor count. As the maximum average factor score is 20, Enjoyment’s 16.2 is 81% of the maximum. In contrast, Immersion’s 8.6 is just 43% of its maximum possible value. However, with a low factor count of 1.3, the Enjoyment factor failed to score the minimum success grade.

The following is the overall CSI equation that was used to find the single CSI score for persuasive cards:

CSI = (17*3 + 16.2*1.3 + 14.2*3.2 + 16*3 + 8.6*1.5 + 16*3)/3

CSI = 75.3

As shown in Table 5, persuasive cards scored 75.3 out of 100. This means persuasive cards would provide reasonable creativity support to users engaged in collaborative creative brainstorming, but they are a C level supporting tool, and there is room for improvement to reach level A in the CSI grading system.

Moving on to the satisfaction rate and ease-of-task rate, the calculated average scores of both is shown in Table 6.

Table 6. The Average Satisfaction Rate and Ease-Of-Task

|

With-card Sessions |

||

|

Name |

Ease of task |

Satisfaction rate |

|

P 1 |

10 |

10 |

|

P 2 |

4 |

5 |

|

P 3 |

8 |

7 |

|

P 4 |

4 |

2 |

|

P 5 |

5 |

9 |

|

P 6 |

4 |

8 |

|

Avg. |

5.8 |

6.8 |

|

Without-card Sessions |

||

|

Name |

Ease of task |

Satisfaction rate |

|

P 7 |

8 |

10 |

|

P 8 |

4 |

10 |

|

P 9 |

3 |

7 |

|

P 10 |

5 |

7 |

|

P 11 |

5 |

9 |

|

P 12 |

4 |

10 |

|

Avg. |

4.8 |

8.8 |

With the understanding that unless the data collected shows a statistically significant difference between groups, we need to hold off from drawing any conclusions about differences, and by running an independent samples t-test shown in Table 6, the independent groups t-test of the ease ratings is t(8) = 0.8, p = .45 and for satisfaction is t(7) = 1.5, p = .18. In neither case is p < .10, much less p < .05. This means that the data is not statistically significant as sample sizes are too low.

Persuasive Cards Pros and Cons

From the open questions and the focus group transcripts, the following noticeable advantages persuasive cards can bring to the design process was observed:

- Brainstorming sessions with persuasive cards are not traditionally boring. Design teams can break the routine by having cards to hold, making the group interaction much easier and more fun rather than going through the persuasive concepts verbally. Also, they provide a gaming element to the sessions which make them a fun interaction between members.

- Persuasive cards provide explanations and examples for novice users. Hand-held tools such as design cards are very helpful for designers in their junior experience phase. Cards not only explain the persuasive features but also give examples for novice designers who have not been exposed to such knowledge, giving them examples they could discuss rather than just a concept.

Also, the cards are based on tested theories, which gives novice designers backup and support for their cause and gives them the rationale behind it. So, cards can work as evidence on the table to make the discussion much more concrete. Moreover, researching all these theories would take a long time, but having them available in a digestible visual is very helpful.

- Persuasive cards are a good starting point, and they keep the conversation flowing. You can easily start with the card game as a brainstorming session involving all team members, which can be a very effective starting point at the beginning of an iterative design process. Also, cards will keep the conversation flowing and moving forward with the ideas as they can add another layer to the conversation or create some debate about how they can be put together. They can help to express and conceptualize important things team members would want to point out and say.

- Persuasive cards are helpful in making the ideation process quicker and more efficient. It is common to have disagreements between members of design teams in ideation sessions; the cards can be helpful as they can give the design team a common ground and help members come to an agreement. In with-card sessions, all participants agreed that it did not take them very long to come up with ideas because the cards kept them structured so they came to an agreement quite quickly.

- Persuasive cards will give you abstracted knowledge to create your actionable ideas. The cards present very high-level abstract knowledge, so they spark the conversation between team members through abstracted persuasive concepts, which they have to make it into actionable and concrete ideas.

Additionally, the following specific drawbacks that persuasive cards can bring to the design process was observed:

- Persuasive cards can introduce a major bias to the design process. The cards provide specific persuasive concepts that have been chosen in advance, which constrain the design space. Additionally, as soon as you provide ways of interrupting these persuasive concepts, you produce bias as there might be many ways of implementing them, but you are immediately introducing an enormous bias to the design space by using these cards.

Moreover, using images and graphic elements can influence the users and push them toward bias behavior. During the sessions when participants were going through the cards, we asked them why they chose to pick some cards and disregard the others, the response to that question was “some images on the cards catch my eyes more than others.”

- Persuasive cards are suitable for initial ideation phase only. This is the time when you are more open about bringing different ideas rather than refining them. They stop at generating ideas and conversational starting points, but when it comes to the wireframing and prototyping phase, persuasive cards cannot be useful as these phases are much more particular and detailed.

- Persuasive cards are time and effort consuming. If the card-deck is designed wrong, it takes time and several uses to get familiar with the cards. Also, brainstorming sessions using persuasive cards could be quite long, and this is only exaggerated with larger teams. As there are a lot of limitations when it comes to time and resources, it seems that persuasive cards would work better for small teams where agreements can be reached more easily.

Design Cards Heuristics

We used the insights from the conducted workshop to create 10 design card heuristics that serve two purposes:

- To be a guideline when it comes to producing and creating card-based tools. Therefore, they would benefit enterprises that are interested in creating persuasive card-based tools for experimental research or commercial products.

- To help designers judge any deck before using it and also benefit from any tools built following the advice derived from these 10 card-based tools design heuristics.

The following 10 design heuristics are presented as possible areas of improvement.

1. The Content of the Card

The content is the most important element of the card, so it is important to make it easy to understand through plain and simple language. Furthermore, it is important to associate each principle with a clear and meaningful title, as the title of the card is the most important piece of information the users are focusing on while scanning the cards.

The cards should provide the knowledge abstractly with a short description. Saying too much will make the card difficult to digest and hinder attention. Also, the cards should not provide actionable sentences, as the cards are not supposed to tell the users what to do exactly, but rather inspire them to create their own actions.

Finally, the cards are only a bridge between theories and practice. Therefore, the cards should only provide theory insights. Thus, a short description, examples, and other information should be abstracted from the theory’s insights itself. Card developers should not provide their own interpretation or explanation, as trying to provide one interpretation over the other could lead to bias.

2. Examples on Cards

The more examples the better, as multiple examples would make the principle clearer and decrease the chances of wrong implementation. Also, good examples can be a substitute for a long description.

It is important to avoid specified examples and go with general concepts instead. For instance, “Black Friday” is a good example, but “Amazon’s Black Friday” is a bad example. Also “showing multiple examples from various directions instead of single case on the cards would make the cards more inclusive to use in different design activities” (Ren et al., 2017, p. 459).

3. Aesthetic and Visual Perception

The biggest obstacle for users to get the most out of the cards is the cards’ visual design, as busy cards can make the visual search difficult, hinder attention, and prevent users from focusing on information relevant to their goal. So, images and graphic elements should not take up half the card space; otherwise, text and other elements are too dense and give an overcrowded look to the cards.

Therefore, the card content needs to be prioritized and the information needs to be structured to support attention and avoid cognitive load. This can be achieved if the text is grouped or chunked into digestible points to support a users’ limited capacity for processing information. Moreover, some details such as title, examples, and a “see also” section need to be highlighted or in bold. All these practices will help the user by making glancing through the cards easier as “when you understand your users’ mental capacity in relation to the tasks they’re trying to achieve, you’ll be well on your way to designing the right features and the right experiences that are sure to hook your users to your product” (Interaction Design Foundation, 2018, “Worksheet: Practice How to Make Use…” section, para. 2).

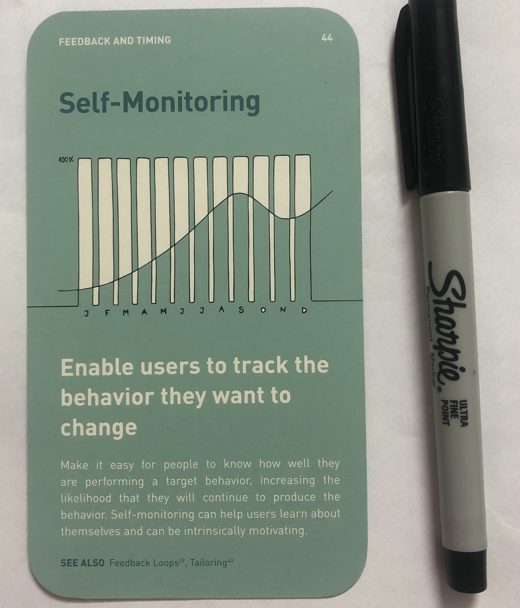

4. Color Contrast and Legibility

Text and other meaningful information should be easily distinguished and read by users, and color choices can play the biggest role in that. The card-deck that was used in this study has white and green-blue text on a slightly lighter green-blue background, which as shown in Figure 5 such colors have low contrast ratios between them. When it comes to color contrast and legibility, contrast ratio affects how readable the text is. For example, if the text is light gray and the background behind it is white that text will be hard to read. Contrast ratio between the text and the background should be at least 4.5:1, and to test the contrast ratio between colors an online checker can be used, such as contrast-ratio.com.

Figure 5. Contrast ratio between text and background color in persuasive pattern card-set.

5. Images and Graphic Elements

Images can influence users and push them toward bias behavior, as some principles can be represented through an eye-catching image more than other principles. These graphical elements can influence users and give some cards a better chance at being picked because a user’s eye is drawn to them more than other cards. Cards can be attractive without images that can take half of the card’s space. Such space can be used more effectively for providing more examples and information.

6. Cards Structure

The card structure is how the main elements on the cards are divided on the card space and presented alongside each other. Such aspects need to be planned in a way that support users’ attention to glance through the cards while searching for information. The structure should be simple and consistent, and the elements should be arranged in an orderly manner.

Therefore, it is important to bring Gestalt principles into practice while structuring the card elements; otherwise, the cards will influence the user’s task, hinder their attention, and put pressure on their working memory. “The key to effectively chunking multimedia content (text as well as images, graphics, videos, buttons, and other elements) is to keep related things close together and aligned (in accordance with the Law of Proximity in Gestalt psychology). Using background colors, horizontal rules, and white space can help users visually distinguish between what’s related and what isn’t.” (Moran, 2016, “Chunking Multimedia Content” section, para. 1).

7. The Number of Cards

It is not efficient to use 60 cards in a brainstorming session, as such a number requires a longer time for people to familiarize themselves with the cards, which can then extend or exceed session times by hours. For example, in a large design team, it will take a long time to go through that number of cards, and it will be difficult to reach an agreement and common ground. A smaller number of cards should help users to scan through them without feeling overwhelmed or lost when trying to select cards.

8. See-also Section

Persuasive principles can be related to each other, and to create persuasive features, several principles may be used to an extent. Creating a link between the cards can help users see and create the bigger picture of the persuasive principles. Additionally, a “see-also” section is effective in helping participants to further explore the cards, generate more ideas, and keep the conversation flowing.

9. The Cards Dimension

The dimension of the cards is critical when it comes to how users interact with them. To be able to provide the content in a way that helps users read and scan through them easily, the physical size of the card should be considered. If the cards are designed too small, then the font size will be small which will affect partly sighted users. A suggestion for the size of the cards is to not go smaller than 11 cm x 15.5 cm in order to have enough space to present information and details appropriately.

10. Distinction and Grouping

If there is no other way to differentiate between the cards apart from reading them, then users will need more time to get familiar with them. This will be time-consuming and could waste hours of ideation sessions, putting pressure on the users’ working memory.

The design of the cards should be done in a way that support users’ conception of the insights either individually or inclusively. This can be done by grouping and using color-codes to distinguish each group. Therefore, it is important to group and color code the cards through different colors within a manageable range to not add an additional distraction to the users. For example, distinguish the motivational persuasion cards to positive and negative through two different colors.

Cards are just external representations, and “when someone externalizes a structure, they are communicating with themselves, as well as making it possible for others to share with them a common focus and thought” (Krish, 2010, p. 444). Therefore, the design of the cards should not become the center of attention. Cards as external representation should give users access to a new operator of getting familiar with the theory’s insights and to see the design space through a holistic view to allow card users to “run this process with greater precision, faster, and longer, and can encode structures of greater complexity” (Krish, 2010, p. 442) outside rather than inside their mind.

Conclusion

The current study revealed that in creative works, the tools that you use influence your outcome. It is not only important to explore what creativity enhancement tools can give, but also what they can take from users. The current study found that persuasive cards can be a double-edged sword that has negative effects as well as positive effects. The most important advantages witnessed were how the cards boosted the communication between the team and kept the conversation flowing. However, introducing bias to the design process was one of the more noticeable drawbacks.

The results of the current study very much build on previous literature in the areas of card-based design tools, and the study provided new insights, such as The Commonality Effect, which was not provided in previous persuasive cards research. Additionally, this paper provided 10 design card heuristics that can be used as a guideline when it comes to producing and evaluating card-based tools.

Moreover, this paper recorded certain behaviors when it came to how novice users interacted with persuasive cards during brainstorming sessions, such as FOMO behavior where participants thought that they missed out on better information from cards that they did not select, and participants debated or neglected their own ideas in deference to the ideas presented on the cards.

While there are various benefits of the current study, there are also some limitations. One of the limitations of the project scope was that only two sessions with persuasive cards were performed and another two without cards. Such a short-term workshop was not enough to see how the cards could directly influence ideation, as any results observed could be an artefact of the personality of the people who were involved in these sessions. However, recruitment of participants took backgrounds and experience into consideration, which resulted in having participants who had already been in different ideation sessions but none of them had used cards before. Such consideration made the workshop procedure and recruiting criteria more rigorous.

Another limitation is using one card deck to evaluate the use of persuasive cards, as different card-sets might lead to different results. To be able to take such effects into consideration, we examined and compared each card from the chosen card deck before using them in the workshop to make sure that the chosen deck had all PSD principles, which every persuasive card deck is using. Therefore, the chosen card deck provided the PSD’s 28 principles and went beyond that to provide more psychological insights with 60 cards.

Future studies need to conduct a long-term workshop with more sessions and a bigger sample size, applying the findings from this study. Also, future studies should test the 10 design cards heuristics presented in this study through comparative and experimental approaches to examine and improve these 10 heuristics. Moreover, future studies should test the suggested further actions to go beyond repetitive and common ideas through an experimental and long-term study.

Furthermore, future studies need to test different persuasive cards against each other to examine if different persuasive card sets might lead to different results. Moreover, future studies need to evaluate the use of persuasive cards in various populations, and it would be interesting to see if the cards have the same effect on participatory methods and different kind of users other than HCI students.

Finally, we recommend future studies to follow an ethnographic field study method, as it would be hard to study what such a tool gives users in short term sessions. Therefore, a true ethnography study is the most suitable technique to study such nature, as “controlled studies in laboratory conditions with standard or ‘toy’ problems over a few hours were seen as inadequate to capture the strategy changes, new possibilities, and learning effects, as they are applied to complex problems. More sympathy was expressed for in-depth longitudinal case studies and ethnographic field study methods to capture the rich texture of activity among creative individuals or groups” (Shneiderman et al., 2006, p. 68).

We hope that the effort in this study to understand what such a tool gives and takes from designers, and the 10 card design heuristics that were produced will keep the discussion going in the HCI community. Hopefully, this study has opened up new avenues for future work in the area of persuasive design cards based on insights and opportunities uncovered during the course of this project.

Tips for Usability Practitioners

Usability practitioners can use the following techniques when using persuasive design cards:

- Brainstorming sessions using design cards are time and effort consuming, and if the card-deck is designed wrong, it takes time and several uses for teams to get familiar with the cards. Therefore, it is very important to evaluate the chosen card-deck against the suggested 10 design card heuristics before deciding to use them.

- Novice practitioners should consider some drawbacks persuasive cards can bring into the design space such as introducing bias as the cards provide specific persuasive concepts that have been chosen in advance, which constrain the design space. Therefore, having a without-cards ideating session before and after using the cards would be beneficial to explore every possibility and expand the design space.

- Practitioners should be aware of The Commonality Effect when using persuasive cards in brainstorming sessions, so they can plan to go beyond repetitive and common ideas from one session and move on to add uniqueness and personality to their outcomes. We suggest the following further actions:

- Have a follow-up brainstorming session without cards, so the team can add their own originality to the ideas that came from using the cards. Or make each ideation session have two to three rounds, and always discard the first round of ideas. The first round is for a warm-up, so you will always discard the result of the first round, and only re-use the outcome of the second round onward. According to the result of the workshop, the first round will mostly generate obvious and common ideas.

- Set a rule for the team to not replicate existing ideas, examples, or suggestions that are written on the cards. Thus, assuring that the team would not repeat themselves.

- Mix and match ideas. It can be challenging to generate new ideas from the second and third round by mixing and matching cards. For example, when picking two random cards, it is the responsibility of the picker to attempt to come up with an idea that consists of the two cards. This approach might help a lot as teams often run out of obvious ideas after the first round and get stuck at the second and third rounds.

Acknowledgements

Our special thanks to all participants who took part in the study and enabled this research to be possible.

References

Ahmed, S., Wallace, K. M., & Blessing, L. T. (2003). Understanding the differences between how novice and experienced designers approach design tasks. Research in Engineering Design, 14(1), 1–11.

Bekker, T., & Antle, A. (2011). Developmentally situated design (DSD): Making theoretical knowledge accessible to designers of children’s technology. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2531–2540). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979312

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), pp.77–101.

Casais, M., Mugge, R., & Desmet, P. M. A. (2016). Using symbolic meaning as a means to design for happiness: The development of a card set for designers. In Proceedings DRS 2016 The Design Research Society 50th anniversary conference. Available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55ca3eafe4b05bb65abd54ff/t/5749b3e9b09f953f2971f39a/1464447994349/424+Casais.pdf

Cherry, E., & Latulipe, C. (2014). Quantifying the Creativity Support of Digital Tools through the Creativity Support Index. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 21(4), pp. 1–25.

Christiaans, H. H. C. M. (1992). Creativity in design: The role of domain knowledge in designing. Lemma BV, Utrecht.

Chung, D., & Liang, R. (2015). Understanding the Usefulness of Ideation Tools with the Grounding Lenses. In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium of Chinese CHI 2015 (pp. 13–22). ACM.

Deng, Y., Antle, A., & Neustaedter, C. (2014). Tango cards: A card-based design tool for informing the design of tangible learning games. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Designing interactive systems (pp. 695–704). https://doi.org/10.1145/2598510.2598601

Fogg, B. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology (Article No.: 40, pp. 1–7). https://doi.org/10.1145/1541948.1541999

Hornecker, E. (2010). Creative idea exploration within the structure of a guiding framework: The card brainstorming game. In Proceedings of the fourth international conference on Tangible, embedded, and embodied interaction (pp. 101–108). https://doi.org/10.1145/1709886.1709905

Interaction Design Foundation (2018). External Cognition in Product Design: 3 Ways to Make Use of External Cognition in Product Design. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/external-cognition-in-product-design-3-ways-to-make-use-of-external-cognition-in-product-design

Krish, D. (2010). Thinking with external representations. AI & SOCIETY, 25(4), pp. 441–454.

Makri, S., Blandford, A., & Cox, A. L. (2011). This is what I’m doing and why: Methodological reflections on a naturalistic think-aloud study of interactive information behaviour. Information Processing and Management, 47(3), pp. 336–348.

Moran, K. (2016). How Chunking Helps Content Processing. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chunking/

Oinas-Kukkonen, H., & Harjumaa, M. (2009). Persuasive systems design: Key issues, process model, and system features. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 24(28). doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.02428

Ren X., Lu Y., Oinas-Kukkonen H., & Brombacher A. (2017). Perswedo: Introducing persuasive principles into the creative design process through a design card-set. In R. Bernhaupt, G. Dalvi, A. K. Joshi, D. Balkrishan, J. O’Neill, & M. Winckler (Eds.), Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science: Vol 10515. Springer, Cham

Rogers, Y., Sharp, H., & Preece, J. (2015). Interaction design: Beyond human-computer interaction (4th Ed.). Wiley.

Roy, R., & Warren, J. P. (2019). Card-based design tools: A review and analysis of 155 card decks for designers and designing. Design Studies, 63, pp. 125–154.

Shneiderman, B., Fischer, G., Czerwinski, M., Resnick, M., Myers, B., Candy, L., Edmonds, E., Eisenberg, M., Giaccardi, E., Hewett, T., Jennings, P., Kules, B., Nakakoji, K., Nunamaker, J., Pausch, R., Selker, T., Sylvan, E., & Terry, M. (2006). Creativity support tools: Report from a U. S. National Science Foundation sponsored workshop. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 20(2), pp. 61–77.

Appendix A: Questionnaires

Creativity Support Index Questionnaire

Part 1

Please rate your agreement with the following statements:

- The cards deck allowed other people to work with me easily.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

- I would be happy to use this cards deck on a regular basis.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

- It was really easy to share ideas and designs with other people using the cards deck.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree -

I enjoyed using this cards deck.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree -

It was easy for me to explore many different ideas, options, designs, or outcomes, using this cards deck.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

- This cards deck was helpful in allowing me to track different ideas, outcomes, or possibilities.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

- I was able to be very creative while doing the activity using this cards deck.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

-

The cards deck allowed me to be very expressive.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

-

My attention was fully tuned to the activity, and I forgot about the cards deck that I was using.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

-

I became so absorbed in the activity that I forgot about the cards deck that I was using.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

-

I was satisfied with what I got out of the cards deck.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

-

What I was able to produce was worth the effort I had to exert to produce it.

Highly Disagree 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Highly Agree

Part 2

For each pair below, please select which factor is more important to you when doing the activity:

“When doing this task, it’s most important that I’m able to…………….”

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

|

| 3. |

|

| 4. |

|

| 5. |

|

| 6. |

|

| 7. |

|

| 8. |

|

| 9. |

|

| 10. |

|

| 11. |

|

| 12. |

|

| 13. |

|

| 14. |

|

| 15. |

|

Part 3

What are the most things you liked about the persuasive design-cards?

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

What are the most things you disliked about the persuasive design-cards?

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Thank you for participating ?

Single Ease and Satisfaction Rate Questionnaire: With-Card Sessions Version

Part 1

- Overall, this task was?

Very easy 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Very difficult

- Rate your overall experience?

Very satisfied 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Very dissatisfied

Single Ease and Satisfaction Rate Questionnaire: Without-Card Sessions Version

- Overall, this task was?

Very easy 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Very difficult - Rate your overall experience?

Very satisfied 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Very dissatisfied

Part 2

What are the most things you liked about this experience?

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

What are the most things you disliked about this experience?

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Thank you for participating ?

Appendix B: Session Setup Photos

The following photographs are from the four sessions that were conducted.

Figure 1B. First team from Session 1 after selecting the persuasive cards they wanted to work with.

Figure 2B. Session 1 persuasive feature/ideas outcome.

Figure 3B. The second team from Session 2 after selecting the persuasive cards that they wanted to work with and writing their ideas on Post-it notes.

Figure 4B. The persuasive feature/ideas outcome from the second team.

Figure 5B. Session 3 persuasive feature/ideas outcome.

Figure 6B. Team 4 persuasive feature/ideas outcome.